Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark was the most popular book to check out in my elementary school library, much to the dismay of our librarian. Whenever I’d be the lucky one to bring it home, I’d page through the stories, scaring myself with the horrifically beautiful illustrations, memorizing—even as I longed to forget—the terrifying tales of men with hook hands, girls scaring themselves to death in cemeteries, ghosts returning again and again to moan and howl and stalk the living for their wrongdoings.

That book is probably a good, solid reason why, when I get up in the middle of the night to go to the bathroom, I pray that nothing moves in the corner of my vision. It is why I dash up the basement stairs, feeling the pressure of a madman behind me with an axe who’s been lurking in the shadows. I still check the backseat of my car whenever I come out of a shopping mall or a grocery store at night, just to be sure, and double check it if some asshole behind me flashes his high beams while driving on the highway.

Ghosts are to fear. They terrorize people. They are not good.I was trained from the get-go, like most of us, that ghosts are scary. My son is 7 years old and already bombarded with images of what a ghost is supposed to be: A floating white sheet with holes for eyes that howls in the attic. Or something to “bust” and put inside a containment unit to stop it from wreaking havoc on the world. Ghosts are to fear. They terrorize people. They are not good.

Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, like any good urban legends or ghost stories, has another purpose besides giving you the shivers, of course. These stories are also instructional tales, giving you guidelines on what to do and what not to do, how to be good and not get killed. Don’t make out with boys. Don’t take drugs. Don’t go anywhere after dark that you shouldn’t be. Don’t mess with the occult. Believe in ghosts—because you’d better take them seriously, or else—but don’t go seeking them out.

***

I listened, for the most part.

I love, in theory, being scared. I’m open to the possibility that there are spirits, demons, energies, we can’t really comprehend, but I don’t necessarily want to experience any of them myself. I’ve freaked myself out with a Ouija board (only during the day), but I’ve never quite had the guts to say “Bloody Mary” in the mirror three times, just in case. If I have a “brand” on social media, it’s that everyone I know sends me pictures of creepy dolls, knowing how delighted I’ll be—but I don’t really want those dolls living in my house.

Generally, we are quick to dismiss the weird, to explain away the unexplained. We want to be “safe scared,” the kind of fear you get in the middle of a crowded theater watching a demon stalk someone on screen. We don’t want to be actually alone and awake in our beds, terrified that the door keeps slamming downstairs, or the lights flickering on and off. We want logic and reason in our life.

For better or worse, we listen to the messages in tales told by campfires—and stay away from things that cannot be explained.

***

Here’s when that changed for me.

My mother died in 2018, in what was otherwise the best year of my life.

That year, I also finished my first novel. Signed with an agent. Sold that book—to a major publisher, for a good deal. All of my dreams came true.

Unfortunately, so did my biggest nightmare.

I got the call that would lead to the offer on my novel about three weeks after the woman that was everything to me left this earth. She never got to read the book. I’d been putting off sending her the manuscript because I wanted it to be perfect, just right, before she read it. When I found out it sold, all the feels went through me–grief alongside elation, excitement alongside heartache—but the most frustrating and terrible thing was not being able to call her and tell her about it.

It seemed wildly unfair that she was just…gone. That there was and would be no way to ever be able to talk to her about it. She had always been my biggest fan. The person who first introduced me to reading. And here was the biggest thing that had happened to my career so far, and she wasn’t there.

***

It wasn’t long after my mother died that I started looking for signs from her. There’s lots of information about this on the internet—Signs Your Loved One Is in Heaven, After-Death Communication, Three Tales that Prove Life After Death, Is Your Deceased Loved One Trying to Talk to You?—discussing visitations, recurring symbols, animals landing near you or trying to get inside, meaningful numbers or songs materializing out of nowhere.

This is what I wanted, desperately. I’d gone from being scared of the ghost stories I’d heard all my life to desperately looking for one of my own.

***

As humans, we are always telling stories. It’s been our way for so many years—our way of understanding, of explaining, of teaching, of scaring. It’s our way of explaining the unexplainable, of understanding our own humanity. And for writers, telling stories is one way of reassuring ourselves that something will live on beyond us. Our words.

In my novel One Night Gone, a young woman disappears without a trace from a wealthy beach town, and no one seems to care. That is, until 30 years later when another woman starts to identify with the young girl’s story. Starts to maybe/maybe not see her in her dreams. Hear her whispering in the walls. Feel her calling to her.

Maybe. Maybe not.

This is not an uncommon theme in my writing. I often explore things that seem a little off, that could or could not be something supernatural. A door slamming in an empty house. A quiet scratching in the walls. An odd image on the screen of a video baby monitor. A figure you swear you saw in your peripheral vision, but when you turn, nothing’s there.

A few weeks after my mom’s death, my aunt called me. “You’re going to think I’m crazy, but…” She told me that a smoke detector kept going off in an unused bedroom in her house. There was no smoke in the room, no one at all using it. The alarm would just beep and beep, and even after she replaced the batteries, it did it again. She finally had to take the batteries out to get it to stop.

My aunt was wholly convinced this was my mom, signaling to her that she was ok.

Maybe not. Maybe.

***

I like the word spirit best. Spirit suggests a soul, a something essential that is still there. Ghost feels emptier. It’s more about what was, a shell of something that once was more. To be a ghost is to be a shadow, a pale replica of a former life. But spirit feels more powerful, more conscious. Less drifting.

I like the word spirit best. Spirit suggests a soul, a something essential that is still there.When we die, is there an energy left behind? Is it the energy of all the love that others have for us, zipping around, trying to find a source that’s gone? Or is it their energy, their souls, their spirits, dissipating? And in that spreading out, in that leaving, are they granted a few wishes or desires? Can they make things happen for the loved ones they leave behind? Present some small source of comfort, however small or weird? A bird, thumping at a window. A soft weight at the foot of the bed. Good news or luck. A strange voice crackling through the cell phone. A smoke detector, wailing and wailing.

When people we love die, do we just naturally look for signs of the ones we’ve lost to deal with our grief? Are we grasping at coincidences, making meaning from nothing?

Or, when we die, are we like the souls in Kevin Brockmeier’s book The Brief History of the Dead, the living-dead who exist in The City until there’s no one left on Earth to remember us? “The living carry us inside them like pearls. We survive only so long as they remember us,” Brockmeier writes. Then we die a second death.

That one seems much more painful to me.

***

A few days after my aunt told me her story about the smoke detector, I sat in our den working on my laptop. The house was quiet—I was alone—and it was a warm September day.

Suddenly, the smoke detector in our hallway, just a few feet from where I was sitting, started beeping in the way it did whenever my husband cooked a sizzling piece of meat. Only this time, there was no cooking going on. No candles that had just been extinguished. No fire downstairs in the fireplace that wasn’t venting properly.

I grabbed a piece of newspaper, waved it in front of the smoke detector until it stopped.

I called my aunt.

Do I believe it was it my mom, signaling to me for some reason through a smoke detector that she was ok? I don’t know. I don’t not believe it. (Ok, yeah, I kind of do believe it.)

I could explain it away—it was a humid day that afternoon, and the door to our back porch had been open. Perhaps the humidity set off the smoke detector. But we’d lived in the house for a year, and had had plenty of humid days with the porch door open. So it seemed odd to have happened then, at that time.

Doesn’t it?

And really, is my story any better or worse than any of the other stories we tell about death? Is it any more or less comforting than the folks who told me my mom was in heaven now and in a better place? Is it any more or less true than the people who say there is nothing at all after death? And does it matter, in the end, what’s true or not, if the story itself brings strength to get through the shittiness that life deals us?

Maybe. Maybe not.

***

I haven’t seen the Scary Stories movie yet, but from the trailer, the plot seems to hinge around an old book or journal that teenagers find, and as they read the stories, they start to come true. This, of course, taps in to all our fears about the otherworld—if we look too closely, listen too carefully, go too far, we’ll find nothing good. Only bad.

But it also proves my point—that our stories live beyond us. The stories we tell—like the way the Japanese remember their dead with food offerings and shrines, or Mexicans honor their dead with a huge parade, dancing, and costumes—help to keep those loved ones, or at least what we loved about them, alive. And remembered. Maybe it would be easier if Americans weren’t so afraid of death and mourning. And how different it would be if we treated ghosts, spirits, and the dead as something to honor and celebrate and not as evil.

When I get up in the middle of the night, I still feel that anxiety about the shadows. I won’t lie—I still worry about seeing a creepy old man ghost hovering at the end of the hallway, looking for his missing toe. But there’s also a little part of me that wishes I’d look and see my mom, too.

And then I remind myself that it’s not all bad. That there could be some good in it, too. And then I feel better.

Even if it’s just a story.

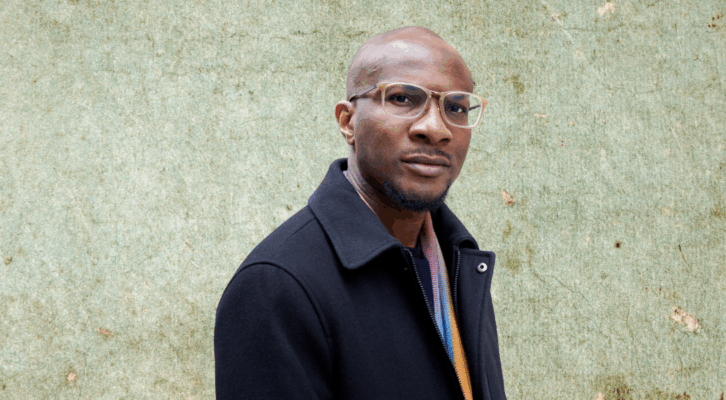

—Featured image: From More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, illust. Stephen Gammell