Unlike me, not every reader has been a die-hard fan of mystery fiction for decades. More likely, you are a fan (else why would you be on a site titled CrimeReads?), but not totally devoted to the genre and basically just looking for some recommendations of what to read but unsure about the various categories by which books may be defined. As a geek who has been professionally involved with crime fiction for nearly a half-century, maybe I can help.

I tend to embrace a wide range of fiction into the mystery genre, defining it as any work of fiction in which a crime or the threat of a crime is central to the theme or plot. This includes the form that most readers regard as a mystery, which is the traditional detective story, but a category of literature that also includes the police procedural, the hard-boiled novel, the tale of psychological suspense, the crime novel, and the thriller. There is enormous overlapping of these sub-genres and it is often difficult to categorize some books.

It is my plan–indeed, my mission–to define these categories, describe their strengths and weaknesses, and provide numerous examples from both the past and the present to help guide readers to the type of book they are most likely to enjoy.

This will be the first of several columns in which I try (you can decide with how much success) to define the major sub-genres.

Since the mystery as a recognized type of literature began with what is now regarded (not surprisingly) as the traditional mystery, that is where I’ll begin, too.

THE TRADITIONAL MYSTERY

STRUCTURE: This very conservative story features a comfortable social structure, such as an English village or an academic institution, which is shockingly disrupted by a murder. A policeman or an amateur (seldom a private investigator in the early years) will attempt to find the killer by traditional investigative techniques, such as questioning suspects, observing clues, and making deductions from them. When the murderer is discovered and hauled away to stand trial, the social fabric is restored.

No one appears to have been affected by the crime, no dramatic change occurs in the relations of the remaining members of the society in which the crime occurred, and there is generally opportunity for humor and romance to flourish. Characters are created as mechanical figures needed to move the plot along and have little depth or inner lives.

Traditional mysteries, even in today’s rather permissive society, tend to contain little in the way of offensive language, dramatic violence, perversion or sex (which may be implied but never described).

HOW TO TELL: If any of the following are mentioned on the dust jacket or cover of the book, you are probably holding a traditional detective novel: gardening, cooking, cats (or occasionally dogs), a university or prep school, a nun, minister, pastor, vicar or rabbi (priests are a little dicier these days), tea, poison, humor, or historical setting.

THE BEGINNING: The American Edgar Allan Poe invented the detective story template that has changed little in more than 160 years. His first tale, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” published in 1841, defined the genre for all time. An apparently impossible crime, a vicious murder in a locked room, baffles the police, who call in the brilliant C. Auguste Dupin and his less-than-brilliant associate, who asks Dupin to explain various clues and deductions to him as a stand-in for the reader, who would like to ask the same questions.

THE GREATS: Poe invented it, but detective fiction did not become popular until Arthur Conan Doyle created Sherlock Holmes. Although officially a private investigator (consulting detective, in the parlance of the time), Holmes served in the same capacity as Dupin, observing everything and deducing with clarity and inspiration.

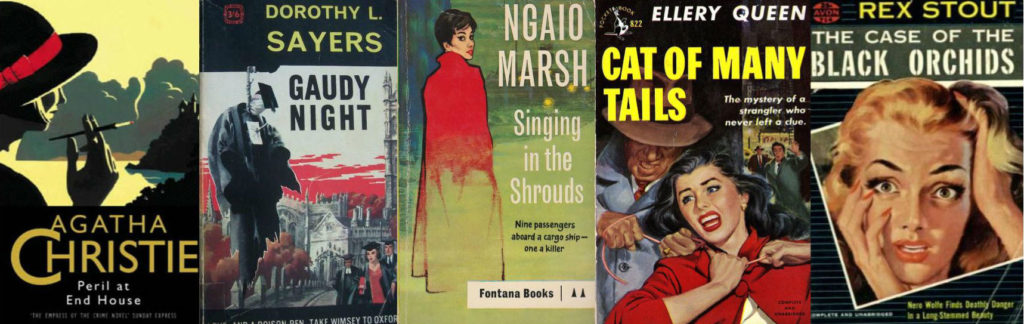

Agatha Christie, who I would argue was the greatest plotter of crime fiction who ever lived, was the 800-pound gorilla in this field, most notably with Miss Jane Marple in her little village and Hercule Poirot, the little Belgian with his “little gray cells.”

In England, Dorothy L. Sayers produced Lord Peter Wimsey novels, and was joined by Margery Allingham (creator of Albert Campion), Anthony Berkeley (with Roger Sheringham), G.K. Chesterton (with Father Brown), Arthur Upfield (with the Australian Napoleon Bonaparte), Nicholas Blake (the Poet Laureate C. Day Lewis, creator of Nigel Strangeways), Josephine Tey (author of the perfect detective novel, The Daughter of Time), Michael Innes (creator of John Appleby), Christianna Brand (author of Green for Danger and other Insp. Cockrill novels), Edmund Crispin (with Gervase Fen) and the New Zealander Ngaio Marsh (with Insp. Roderick Alleyn).

American writers who epitomized this form include Ellery Queen (two cousins who were smart enough to give their detective the same name as their pseudonym, helping readers remember it), Erle Derr Biggers (creator of Charlie Chan), S.S. Van Dine (whose insufferably pedantic detective, Philo Vance, needed, as Ogden Nash poetically stated it, “a kick in the pance”), Mary Roberts Rinehart (among the first best-selling mystery writers and unwitting creator of the “Had-I-But-Known” school of mystery writing), John Dickson Carr (master of the impossible crime puzzle), Stuart Palmer (with the inimitable Miss Hildegarde Withers), and Rex Stout, whose corpulent Nero Wolfe was the ultimate armchair detective.

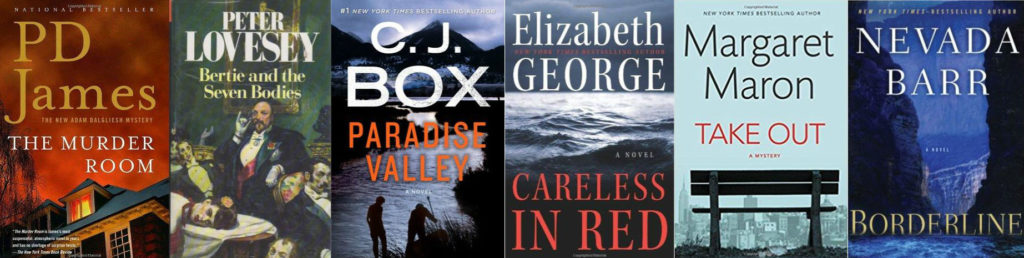

BEST OF THE MODERNS: British writers in the sub-genre you will enjoy include P.D. James (though, admittedly, she’s far from cozy, and does create real characters with varied inner lives; she may be the best British crime writer of the past half-century and there’s no other category into which she would fit), Peter Lovesey, Robert Barnard, Anne Perry, Simon Brett, H.R.F. Keating (especially the Ganesh Ghote novels set in India). Some others that you might enjoy are Marian Babson, June Thompson, Rhys Bowen, M.C. Beaton, Ann Granger, Jill McGown and Janet Laurence.

The best American authors of traditional mystery fiction include Elizabeth George (much darker than most, but what a writer!), C.J. Box, Laura Lippman, Elizabeth Peters, Aaron Elkins, Parnell Hall, Charles Todd, Nevada Barr, Laurie R. King, Margaret Maron, and Deborah Crombie. Some others you might enjoy include Lillian Jackson Braun, Carolyn Hart, Joan Hess, Diane Mott Davidson, Nancy Pickard, Carole Nelson Douglas, and Jill Churchill.