The domestic blowback of the Vietnam War. The sleaze and corruption of Watergate. The incipient rollback of the counterculture and many gains of the 1960s. Economic recession. The upheaval and uncertainty in the 1970s may have been tough on America’s collective psyche, but it resulted in some incredibly good crime cinema, particularly prior to Jaws in 1975, which helped to usher in the culture of the cinematic blockbuster. And while I will happily admit to being a due paying member of the First-half-of-the-1970s-was-a-great-period-of-American-crime-cinema-fan-club, it does strike me that we tend to focus on the same handful of films from this period over and over. Yes, The French Connection and Shaft (1971), The Godfather (1972), The Friends of Eddie Coyle and The Long Goodbye (1973), and Chinatown (1974), are all masterful neo noirs that in some way enlarged the culture’s notion of what crime cinema could be. But the wellspring of American neo noir on the screen in the first half of the decade runs very deep, and it pays major viewing dividends to explore it more widely. Here are ten underappreciated neo noirs from the first half of the seventies that are worth your time.

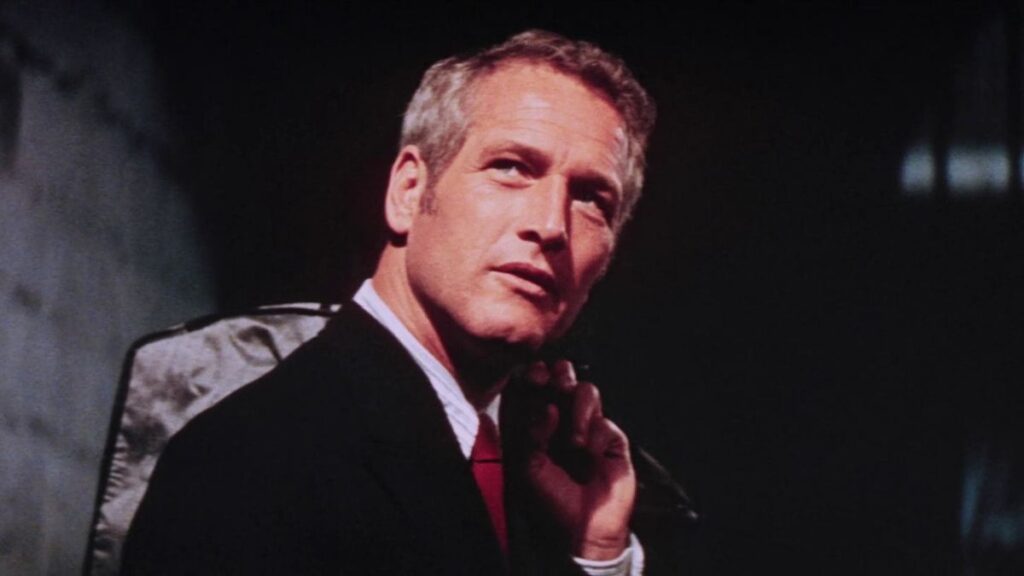

WUSA (1970)

A fascinating character study of three individuals who wash up in New Orleans at the wrong place and the wrong time: Geraldine (Joanne Woodward), a hustler fleeing an abusive marriage; Rainey (Anthony Perkins) an idealistic Christian who wants to help the city’s poor but who, unbeknownst to him, has been set up by shadowy forces as part of a plan to force the black population off welfare; and Rheinhardt (Paul Newman), a cynical alcoholic drifter, who falls into a job on a local radio station ran by a right-wing firebrand called Bingamon. Only Rainey retains a glimmer of idealism and, upon discovering his job is a farce, takes matters into his own hands, triggering a terrible series of events. WUSA’s screenplay was written by novelist Robert Stone based on his 1967 novel, Hall of Mirrors, and helmed by Stuart Rosenburg, a largely forgotten director now who delivered a terrific string of crime films in the late 1960s and 1970s, including Cool Hand Luke (1967), The Laughing Policeman (1973, included in this list) and The Drowning Pool (1975). In addition to some wonderful early 1970s New Orleans period detail, WUSA has a great supporting cast, including Laurence Harvey as a fake priest and Pat Hingle (the mob boss Bobo Justus in the 1990 adaptation of the Jim Thompson novel, The Grifters) as Bingamon. Just how close this film comes to predicating America’s current politics will unnerve you.

Wanda (1970)

Wanda is the story of a poverty-stricken young woman who leaves her husband and two small children to wander through Pennsylvania coal country. She hooks up with a tightly wound and borderline abusive small-time stickup man, who draws her into his plans for one last big score, the execution of which goes horribly wrong. For various reasons, Wanda was unfortunately the sole directorial effort of Barbara Loden, who also wrote and starred in the film. The stark gritty feel, the result of its meagre budget of $115,000, and minimalist storytelling style combine to deliver real emotional heft. While Loden’s Wanda has not wanted for critical attention, having received its own Criterion release and been the subject of two academic monographs, the commentary around it has understandably focused on the marginalisation of women in the American film industry and Loden’s role as an, until recently, unacknowledged pioneering female filmmaker. But I would strongly argue it can also be read as a neo noir, possessing the elements of a heist thriller and a central narrative about a woman dealing with a world in which she has little control and getting slowly sucked into committing a serious criminal act.

The Day of the Wolves (1971)

Whether by coincidence or design, the plot of Day of the Wolves has definite similarities to The Score, the 1964 novel featuring the character of the master criminal Parker by Richard Stark (aka Donald Westlake). Six criminals are summoned to a ghost town in the middle of the Arizona desert by a mysterious anonymous criminal mastermind and offered a large sum of money to take part in robbing a nearby town called Wellerton of all its wealth. The men are assigned numbers for their names and put through a rigorous training regime in the ghost town before being unleashed on Wellerton. While things go well at first, the gang have not factored into their plans Wellerton’s disgraced former sheriff (Richard Egan) and his wife (Martha Hyer). No argument, this is one of the harder films on this list to find, which is a pity because it is an innovative take on the heist story. It was made for American TV but apparently was also shown theatrically in various European countries.

Top of the Heap (1972)

Like Loden, African American actor Christopher St John, probably best known for his supporting role in Shaft, directed just one film, Top of the Heap. St John also wrote the story and plays the main character, Lattimer, a black member of the Los Angeles Police Department. Psychologically and emotionally ground down by financial and family difficulties, including an unreconciled relationship with his recently deceased mother, and all enveloping racism he experiences in an overwhelmingly white police force, he embarks on a one-man crusade against organised crime interspersed with vivid hallucinations that he is a NASA astronaut in training for a moon landing. It is hard to say much more about Top of the Heap without giving to away the rest of the story and prefiguring how the viewer might interpret this film. Part psychedelic trip, part hard boiled cop story, and part Blaxsploitation cinema, Top of the Heap is fascinating film that both pushes the boundaries of crime cinema and offers a blistering take on urban race relations in early 1970s America.

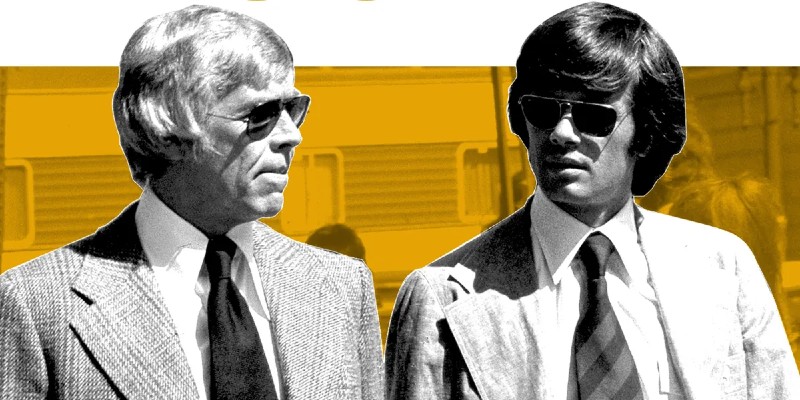

The Laughing Policeman (1973)

The Laughing Policeman is based on the book by Swedish husband and wife crime-writing duo Per Wahlöö and Maj Sjöwall, one of ten they wrote featuring the left-wing Stockholm police detective Martin Block. Directed by Rosenburg, who did the honours on WUSA, the film version transplants the story to San Francisco and focuses on two cops, Martin and Larson, Walter Matthau and Bruce Dern respectively, who get caught up in a series of increasingly life-threatening events in an attempt to solve the massacre of eight passengers on a late-night commuter bus, among the victims of which was another cop. Although not often thought of as such, The Laughing Policeman arguably belongs in the small body of American films with a distinct giallo sensibility. It features a decent car chase and a great supporting cast that includes Lou Gossett Jr as another police detective and one of my favourite American character actors, Anthony Zerbe, as the police commander in charge of the case.

Save the Tiger (1973)

Another film I am keen to claim as a neo noir, even though it is not usually thought of as such. Jack Lemmon is Harry Stoner, the ennui riven middle class co-owner of a sinking Los Angeles fashion label. He and his business partner, Phil Greene (played by the wonderful character actor Jack Gilford) have managed to keep their company open through fraudulent accounting but are struggling to stay afloat as the recession that hit America in the early 1970s starts to bite. As a solution, Stoner hatches a plan to burn the business’s warehouse down for the insurance money. Directed by John G. Avildsen and based on a 1971 novel of the same name by Steve Shagan, Save the Tiger is a slow burn story with some great local colour: the scenes where Stoner and Greene meet their intended arsonist to negotiate the details of the job in an old LA cinema playing a Swedish sexploitation film are almost worth the admission price. There is also an interesting subplot in which Stoner, who is also dealing with a long undiagnosed case of PTSD dating back to his army service in WWII, strikes up a relationship with a hippie female hitchhiker he picks up on Sunset Strip, which echoes Tarantino’s Cliff Booth doing the same almost half a century later in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019).

Harry in Your Pocket (1973)

Compared to most of his joyously mojo intensive cinematic romps in the 1960s and 1970s, Harry in Your Pocket sees James Coburn deliver a downbeat, even taciturn, performance as the professional pickpocket of the title. Working with his long-term offsider, Casey (Walter Pidgeon), Harry recruits two young drifters, played by Michael Sarazin and Trish Van Devere, and educates them in the art of pickpocketing. There is a definite caper feel to aspects of this film, especially the wonderfully choreographed sequences in which the four team members coordinate various pick pocketing scams on unsuspecting members of the public, set to a lush Lalo Schifrin score. But for the most part this is a stripped back, tough nut of a story, riffing off the well-worn trope of the career grifter who can’t stop plying their trade even as they sense the times are no longer favourable to them.

The Nickel Ride (1974)

Jason Miller, fresh from the success of 1973’s The Exorcist, is Cooper, a mid-level operative in the Los Angeles organised crime scene, who managers several downtown warehouses where the mob stash their stolen merchandise. This job has earned the nickname of ‘Key Man’ due to all the keys to various storage facilities he carries around. As he tries to finalise negotiations on large tract of old commercial warehouse space that would be perfect to expand their operations, Cooper’s immediate boss, Carl (John Hillerman, instantly recognisable as Higgins in Magnum PI), assigns Turner (the recently departed Bo Hopkins), a cocky cowboy enforcer, to shadow him. Is Turner just hanging around to learn the basics of the business or does he have more dangerous designs? Director Robert Mulligan delivers a low-key tale with almost dream-like pacing. The closest cinematic analogy is The Friends of Eddie Coyle, which also featured an ageing, low level mob figure who has lost his taste for the criminal world and has to fight for survival against younger, hungrier, up and comers. Miller is excellent as is Linda Haynes as his ex-dancer girlfriend. In my humble opinion, one of the most underrated crime films of the 1970s.

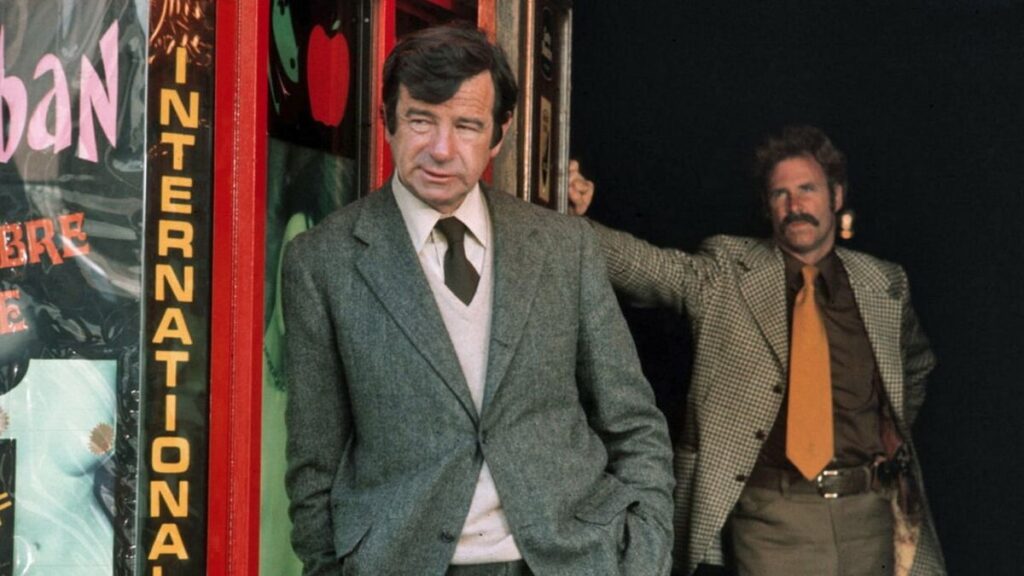

Busting (1974)

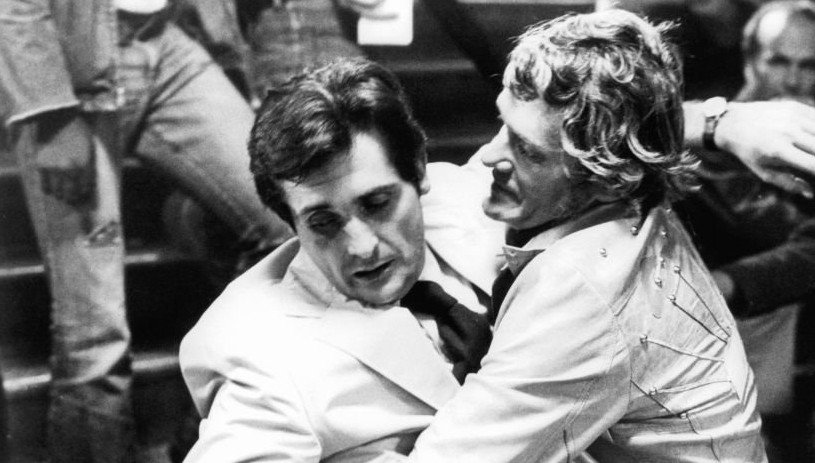

Elliot Gould and Robert Blake are Keneely and Farrel, two hard charging Los Angeles vice cops. Both will not stop pushing back against the tidal wave of vice sweeping the city and efforts to make a case against a local mobster cum pimp, even when it is clear the two men are getting no support from their own department, and they are bumping up against a major narcotics smuggling operation. While Busting might seem like a strange choice for Gould coming straight off The Long Goodbye, there are definite thematic similarities. Gould’s characters in both films are laconic, rebellious and deceptively determined individuals. In addition to the requisite 1970s black humour, Busting also features some great action set pieces, including a nail-biting extended chase sequence.

Report to the Commissioner (1975)

Yet another entry in the body of New York set crime cinema to depict the metropolis in the 1970s as being on the verge of complete anarchy, Report to the Commissioner opens with the discovery of the body of a murdered woman in a loft apartment in a run-down part of the city. It is quickly revealed that the deceased was a policewoman (Susan Blakely) working an unorthodox undercover operation to snare a charismatic African American drug dealer with suspected links to black militant organisations. The resulting scandal and high-level investigation rapidly focuses on the role of Detective Bo Lockley (Michael Moriarty), a young progressive rookie hopelessly out of his element in a tough inner-city precinct, who is being fitted up as the fall guy for the mistakes of much more senior police. Report to the Commissioner deals with inner city crime, mental illness, racism, and police corruption. As if this was not enough, the plot almost completely pivots about two thirds of the way through, further upending stereotypes around race and gender. An absolute hand grenade of a neo noir, that features a who’s who cast of 1970s crime film talent, including Yaphet Kotto as Lockley’s brutal but essentially decent older partner and a very young Richard Gere as a pimp.