While preparing for a recent appearance on a podcast episode about John Boorman’s 1967 film, Point Blank, I thought a lot about American noir cinema of the very late 1950s and the 1960s. I find it interesting that so many of the films made during this time remain unknown and underappreciated relative to the classic film noir period, generally regarded as beginning with John Huston’s 1941 classic The Maltese Falcon and ending in 1958, and the body of American crime cinema known as neo noir, which took off in the early 1970s.

I have no desire to reprise the ‘what is noir?’ debate. I also realise that it is impossible to put firm boundaries between periods of cinema. Some argue classic film noir continued to be made until the mid-1960s, when black and white ceased being commercially viable. Neo noir’s origins are also heavily contested. But at the very least, both classic film noir and neo noir embody definite stylistic techniques and thematic trends. For example, film noir is known for its titled camera angles, interplay of shadow and light, and often-unbalanced framing, all of which owe a debt to pre-war European cinema and the writers and directors who fled Nazism in the 1930s and early 1940s. Narratively, film noir blurred the lines between good and bad, although under the Hays Code’s strictures, this was often muted.

The term neo noir is primarily associated with the subversion of classic film noir tropes, the anti-hero, the femme fatale, the bad town, etc. David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) is just one of many brilliant examples. According to crime scholar Lee Horsley, it has also been characterised by the way it aped the styles, fashions and social mores of the 1940s and 1950s, in such a way as to play on what was then an emerging postmodern fascination with things ‘retro’ and a nostalgic avoidance of contemporary experience. Chinatown (1974) could be cited as an example, although the neo noir as homage became a much more overt cycle in the 1980s with films like Body Heat (1981) and Against All Odds (1984), remakes of Double Indemnity (1944) and Out of the Past (1947) respectively.

In a comment to me on social media, Kevin Burton Smith, the man behind the Thrilling Detective website, called the years between 1958 and the end of the 1960s ‘the outlier decade’ in terms of American cinema, as there was no definite sense of a movement, as was the case in the 1950s and 1970s. Indeed, many of the best American noirs made at the end of the 1950s and during the 1960s can almost feel as though they were filmed in quarantine from each other. That this body of cinema had no one cohesive set of stylistic and narrative conventions is perhaps linked to rapidly shifting film making technologies and new film influences. The latter obviously encompassed European New Wave cinema, but also sexploitation films, the term for the wave of independently produced low budget movies that while tame by today’s standards pushed the envelope in terms of sexual situations and nudity. I would also argue that American noir of the 1960s exhibits a marked tonal shift from earlier film noir, less lush, harsher and more garish. The sense of possibility that was present in the aftermath of the end of global war is long gone as dominant structures have regrouped and life is carried on in the shadow of the Cold War and nuclear annihilation.

Whatever the case, this outlier decade resulted in an incredibly interesting and diverse body of American noir, which, with some exceptions, Point Blank being one, remain under viewed and unappreciated. Here are ten such American noir films that I think are worth your time.

The Crimson Kimono (1959)

Much of Sam Fuller’s work post-classic film noir is ripe for rediscovery, but The Crimson Kimono is particularly unknown. Written and directed by Fuller, the story sees a cop buddy duo, played by Glenn Corbett and Asian-American actor James Shigeta, assigned to investigate the murder of a burlesque singer in a seedy part of Los Angeles. The two subsequently fall out over their affections for a female artist (Victoria Shaw), a key witness in the case. This solid crime film incorporates the then forbidden topic interracial love alongside fascinating images of 1950s Japanese LA.

City of Fear (1959)

Irving Lerner was a left-wing cinematic polyglot whose largely undocumented career spanned the large and small screen from the 1940s to the early 1970s. One of two existentially bleak noirs he helmed in the late 1950s, City of Fear, plays like a tougher version of Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955). A violent criminal (Vince Edwards) busts out of prison and makes his way to Los Angeles with a steel cannister, which unbeknownst to him contains the deadly radioactive substance Cobalt-60. Can the police catch him before he endangers millions of the city’s inhabitants? This bare bones B noir is further elevated by a wonderful Jerry Goldsmith score (only his second) and terrific location photography by cinematographer Lucien Ballard.

Private Property (1960)

A blend of noir and the youthsploitation films popular at the time, Private Property sees two vicious opportunistic drifters, played by Corey Allen and a very young Warren Oates, follow an unhappily married woman (Kate Manx) back to her home where the three engage in a bizarre game of psychosexual cat and mouse. Shot in ten days on a shoestring budget, the film was written and directed by The Outer Limits creator Lesley Steven. Condemned by morals groups for its sexual content, it became unavailable when its distributor went out of business, making it a genuinely lost film until 2016, when it was re-released on Blu-ray.

Johnny Cool (1963)

Henry Silva is at his psychopathic best as a war orphan turned Sicilian bandit turned professional hit man, who is renamed Johnny Cool and unleashed by an exiled American gangster on his syndicate rivals in New York and Las Vegas. Johnny Cool has a harsh staccato feel and tone. And while the plot does not quite fit together, this is more than made up for by the film’s turbo charged narrative and pulp noir sensibility. In addition to Elizabeth Montgomery as Cool’s somewhat unwitting rich girl accomplice, the film includes Telly Savalas, Richard Anderson, Brad Dexter, John McGiver, Sammy Davis Jr, Elisha Cook Jr and Wanda Hendrix.

Who Killed Teddy Bear (1965)

Female disc jockey, Norah (Juliet Prowse), is a victim of obscene phone calls. A policeman, whose own wife was raped and murdered, and who believes the calls will escalate into more dangerous behaviour, seeks to help her. The stalker, a young man called Larry (Sal Mineo), who buses tables at the same disco Norah works at, has major psychological problems due to childhood trauma. But the film also suggests his condition is made worse from exposure to the permissive culture of New York’s Times Square in the mid-1960s, a wonderfully rendered world of burlesque shows, sex cinemas, peep shows, and dirty bookstores. Who Killed Teddy Bear is a fascinating noir that feels very much ahead of its time in terms of its nods to the erotic psychological thriller genre that would emerge in the late 1970s.

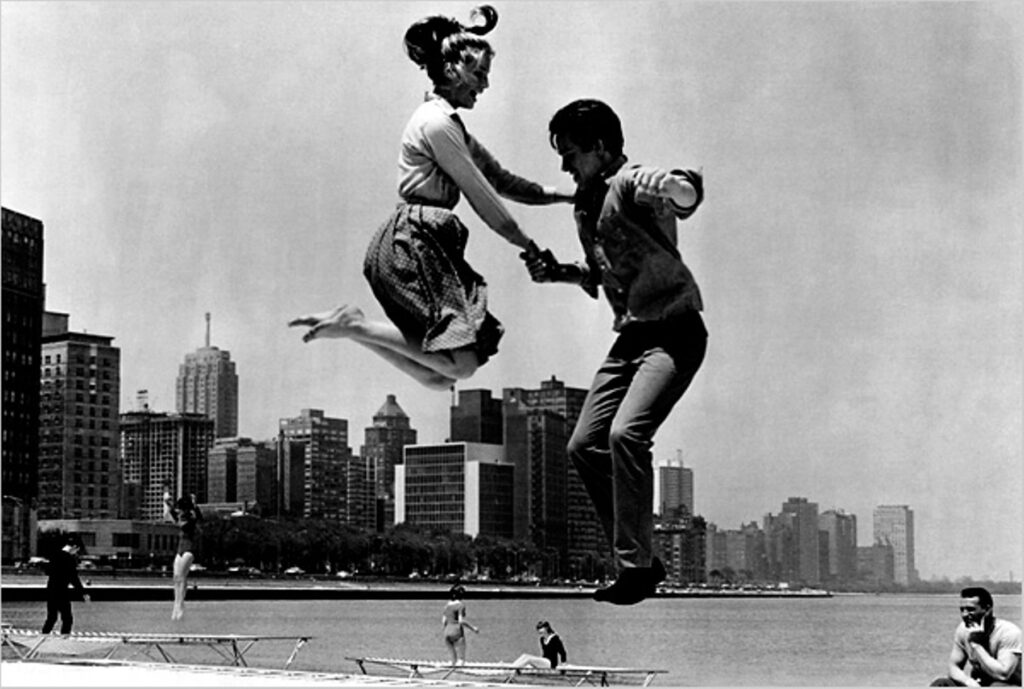

Mickey One (1965)

Two years before he shocked cinema audience with Bonnie and Clyde, Arthur Penn directed this story of a small time, womanising Detroit stand-up comedian called Mickey (Warren Beatty), who goes on the run from an anonymous criminal organisation for a life-threatening infraction, the exact nature of which he is unclear about. He starts a new life in Chicago, where he begins to experience success on the city’s nightclub circuit and falls into a relationship with a loving woman (Alexandra Stewart). But Mickey remains wracked with paranoia that his past will catch up with him. Surreal and dreamlike, this innovative film owes a major debt to European new wave cinema. There is also a cracking soundtrack by jazz musician Stan Getz.

Seconds (1966)

While this is the most critically lauded of the titles on this list (including having its own Criterion release), I would still argue John Frankenheimer’s Seconds remains criminally underseen. Bored, ennui riven New York white collar wage slave (John Randolph) makes a Faustian pact with a mysterious corporate entity to receive a new body and face and a second chance at life as a bohemian artist in California. But can the man (played in his new incarnation by Rock Hudson) escape his past? The third of Frakenherimer’s paranoia cycle of films, Seconds bombed upon release, largely because audiences could not fathom Hollywood heartthrob Hudson in such an outré role. But watched now, this blend of noir and science fiction not only provides an insight into Hudson’s own career, but brilliantly catches the mood of an America on the cusp of the Summer of Love.

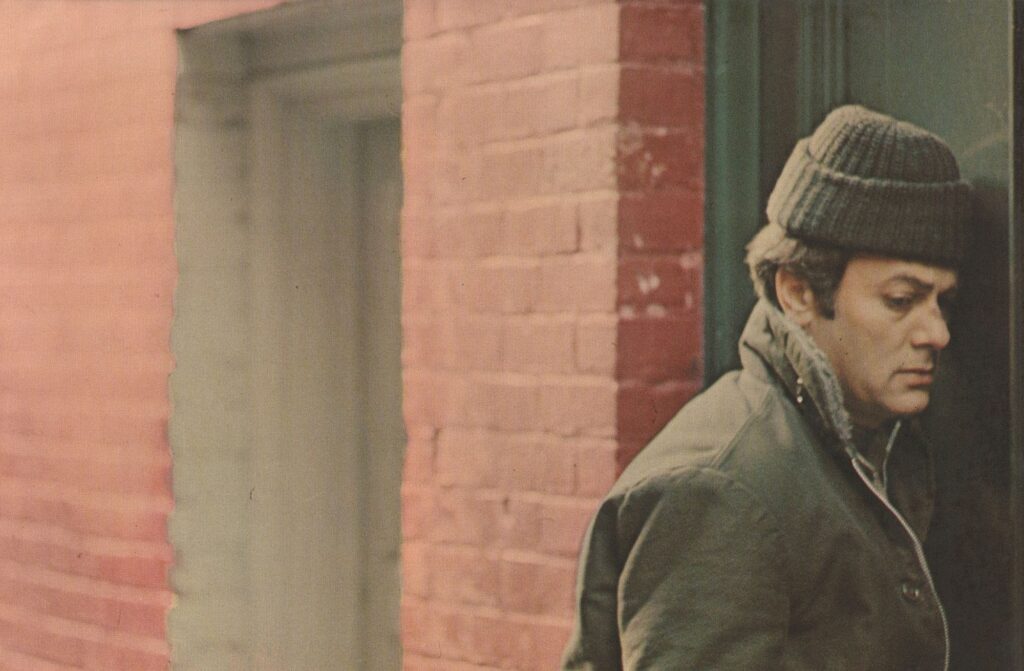

The Boston Strangler (1968)

Richard Fleischer’s The Boston Strangler featured another major departure for a Hollywood leading man, a stunning performance by Tony Curtis as Alberto DeSalvo, the real-life killer who murdered 13 women in Boston in the early 1960s. Combining noir and true crime tropes, the first half of the film shows police trying to track down the killer. The story then pivots in an unexpected direction when De Salvo is apprehended. Fleischer makes good use of montages, vox pop interviews, and split screens to simultaneously convey three narrative strands: DeSalvo stalking his victims; police efforts to catch the killer, biased towards focusing on certain parts of the city’s population; and the female population of Boston’s terror at having a serial killer in their midst.

The Detective (1968)

In terms of crime cinema, Frank Sinatra’s persona in the second half of the 1960s is arguably most associated with the hardboiled swinging sixties Miami private detective Tony Rome. But veteran director Gordon Douglas’s The Detective gave Sinatra the opportunity to deliver a very different role as NYPD detective Joe Leland. Assigned to investigate the murder of a gay man, Leland spends a much time dealing with the prejudices of his fellow police as finding the killer. Hollywood simply did not have the language to talk openly about homosexuality in the late 1960s, which makes The Detective’s themes somewhat hooded. Nonetheless, Sinatra delivers a solid, nuanced and sensitive performance. The film, controversial for its time, also has a powerhouse supporting cast, including Lee Remick, Jacqueline Bisset and Robert Duvall.

Uptight (1968)

This criminally little-known noir directed by Jules Dassin, his first film made in America since leaving the country in 1953 after being blacklisted by HUAC, was a collaboration with Black playwright Julian Mayfield and civil rights campaigner and actress Ruby Dee. Set in the industrial section of Cleveland Ohio on the night of Martin Luther King’s assassination, it depicts the aftermath of a heist by a group of Black militants, which leaves a security guard dead and one of the militants, Johnny, on the run. Johnny’s childhood friend (Mayfield), an unemployed, alcoholic ex-steelworker who was supposed to participate in the robbery but failed to appear due to his drinking, comes under pressure from the black militants and from the police to give up his friend. A mix of classic film noir and more neo realist influences, this film is a razor-sharp depiction of the politics of the time.