Cinema is infatuated with prison stories. There’s something cinematic about them: the violence; the social behavior and relations of all those within the correctional system; and the striking ways in which convicts “MacGyver” tools for survival in these cutthroat environments. A small subset of these tales, however, derives from texts written by actual inmates, adding a level of authenticity and detail to the stories. Although by no means exhaustive, these dozen films demonstrate the myriad ways in which the criminally penned prison film takes shape around the world: from gulags to military brigs, from penal colonies to POW camps and maximum-security prisons.

I Want to Live! (Robert Wise, 1958)

Far more prestigious than the usual exploitative “women in prison” films, I Want to Live! sees a ferocious Susan Hayward giving an Oscar-winning performance as Barbara Graham, a femme fatale who was sent to the gas chamber in San Quentin for the March 1953 murder of a housewife. Based on an amalgam of sources (newspaper and magazine articles, letters, court records) by Graham and Edward S. Montgomery, the Pulitzer-winning writer reporting on the story, the film makes an effort to prove her innocence and throw a harsh light on capital punishment (it even begins with a lengthy preface by “Nobel Prize Winner” Albert Camus).

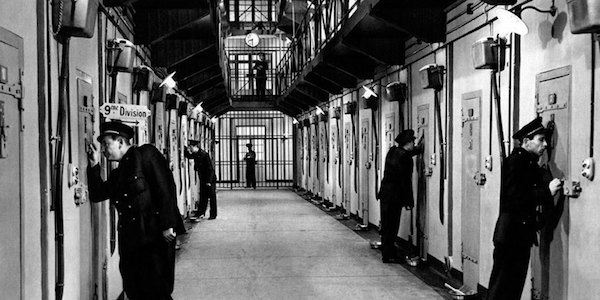

Le Trou (Jacques Becker, 1960)

Jacques Becker’s final feature is a tense, carefully orchestrated film from stem to stern and rightfully deserves to be called a “classic.” José Giovanni, a man who lived a full life, was a criminal and fighter in the French Resistance. Once sentenced to the guillotine, which was then commuted to life in prison, Giovanni served eight years of hard labor before being released. Afterwards, he made good use of his life experience and began writing novels, memoirs, and screenplays, and directing a number of movies, often in the genre of film policier. Le Trou is based on Giovanni’s first book, a fictionalized account of his attempted breakout from the Santé prison in 1947.

The Brig (Jonas Mekas, 1964)

Helmed by an icon of American avant-garde cinema (to be sure, this is Jonas Mekas’ oddest project), The Brig is an immersive recording of the Living Theatre’s production of The Brig, a play conceived by Kenneth H. Brown and based on his time in one on Mount Fuji during World War II. The play, partly inspired by Antonin Artaud, Bertolt Brecht, and Vsevolod Meyerhold’s Biomechanics technique, and stage directed by Judith Malina, is an aggressive account of a single day in the brig, highlighting the abuse of power by army officials and the system of rules that the soldiers must strictly follow, effectively dehumanizing them.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (Caspar Wrede, 1970)

There are few films based on the words of those who survived the Soviet gulags. There are few films based on the gulags period. This fairly faithful adaptation of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s novel is in dire need of restoration. It’s available on YouTube, but the videos are in terrible shape, rendering the picture fuzzy and dark. Too bad, for Ingmar Bergman’s go-to cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, lenses the film. True to its name, we see a day in the life of Denisovich (Tom Courtenay) marching to work, laboring with brick and mortar, eating, and feeling sick. The film doesn’t so much as depict the violence of survival but the rote actions taken to stay alive in a Siberian labor camp for political prisoners.

Papillon (Franklin J. Schaffner, 1973)

In 1969, Henri Charrière published Papillon—his partly true, partly fictional account of his 13-year incarceration in the French Guiana penal system—which became an instant bestseller. Four years later, the thick book turned into a big budget Hollywood film starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman. Aside from the camaraderie, the brotherhood, and solidarity among prisoners, Papillon, in over two hours, details what Charrière supposedly went through: doing hard labor in swamps, serving years in solitary confinement, and finally being imprisoned on the dreaded and remote Devil’s Island. Let’s see if Charlie Hunnam and Rami Malek have the star power to invigorate the new version of Papillon, which comes out later this month.

The Consequence (Wolfgang Peterson, 1977)

Loosely based on writer and actor Alexander Ziegler’s life, this West German made-for-TV film sees a 30-something (a simmering Jürgen Prochnow) locked up for falling in love with an underage boy. There, he starts a new, doomed romance with the warden’s 15-year-old son (a delicate Ernst Hannawald) that continues upon his release. First Ziegler’s book and then this adaptation raised awareness of homosexuality and homophobia in the country at the time.

Midnight Express (Alan Parker, 1978)

A surprise hit, this shrill, xenophobic, and over-the-top film directed by Alan Parker and scripted by Oliver Stone hasn’t aged well. It’s perhaps a lesson in what not to do when making a prison film. Freely adapted from small-time drug smuggler Billy Hayes’ eponymous 1977 autobiographical novel, recounting the harrowing tale of serving five years in a Turkish prison before escaping. People remember its absurdity (gleefully violent, the oft lampooned visit by Billy’s girlfriend, who exposes her breast to him) but not the fact that the film damaged Turkish-American relations, shrinking tourism to the Middle Eastern country. Invited back to Turkey in 2007, Hayes has been making amends and repairing the harm that the film has done by performing in a one-man show, appearing in the press, and being the focus of a documentary.

A Sense of Freedom (John Mackenzie, 1979)

Another made-for-TV film, this one on Scottish gangster and moneylender turned bestselling author and sculptor—Jimmy Boyle. Shot with handheld cameras, this is a visceral film in which little over half of the running time is devoted to Boyle’s stay in several prisons, capturing not only his resistance (smearing shit on himself, breaking through the weak prison walls) but also the tedium that plagues him. Mackenzie’s film ends with Boyle entering a special unit of Barlinnie prison where he would go on to write his life story and the book that the film derives from.

Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (Nagisa Oshima, 1983)

Nagisa Oshima, Takeshi Kitano, David Bowie, Ryuichi Sakamoto—Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence is stacked with talent. It is a haunting, dream-like tale (all the more so by Sakamoto’s score) of juggling, maneuvering, and ultimately clashing cultural differences between Japanese and English soldiers set in a 1942 Japanese POW camp in Java. Adding to the oneirism, Oshima scrambles the plot of the overlapping tripartite stories told in Laurens van der Post’s The Seed and the Sower, for which the movie is based off of.

In the Name of the Father (Jim Sheridan, 1993)

Gerry Conlon, who wrote Proved Innocent, wrongfully served 15 years in various prisons for the Guildford pub bombings. Along with Conlon, his close friends and family served time as known associates, conspirators, and instigators for a terrorist attack that they never in fact did. In Sheridan’s Hollywood film, Daniel Day-Lewis depicts the growth of Conlon during his long stint in prison, from wily and youthful to mature and independent, finally becoming a man and honoring and loving his father (who served time with Conlon before dying).

Chopper (Andrew Dominik, 2000)

Professional thug and expert media manipulator Mark “Chopper” Read published a string of bestselling fiction and nonfiction books, the latter of which exaggerated his criminal exploits. Using his life and his writing, Andrew Dominik made one of the best films of this century, creating a work that transmutes the brash are-they-true-or-aren’t-they-true tales of the many personas of Chopper into film form, using editing, color, and sound to create a perpetually disorderly film. It doesn’t hurt either that Eric Bana gives a singular performance as Chopper, the likes of which we’ll probably never see from him again.

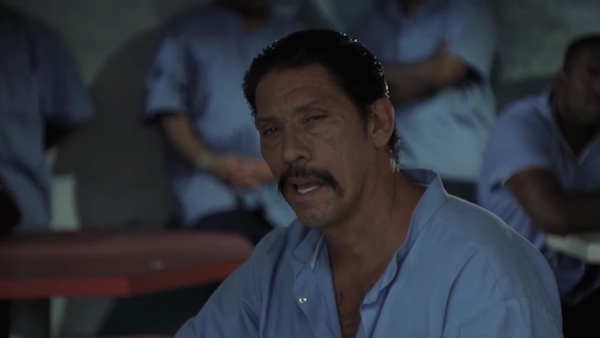

Animal Factory (Steve Buscemi, 2000)

Although it lacks the gritty, terse gutter poetry of felon turned crime writer Ed Bunker, Steve Buscemi shoots his Reservoir Dogs (1992) co-star’s material with an unfussy, straightforward approach that works wonders to shine a light on the ensemble cast (Willem Dafoe, Edward Furlong, Danny Trejo, Mark Boone Junior, Mickey Rourke, Seymour Cassel, John Heard, and Tom Arnold). Like Le Trou, Papillon, and Chopper, Animal Factory describes the brotherly bonds among inmates. Homosocial relations are built on ties of trust, respect, and loyalty; if these ties are violated, there are dire consequences.