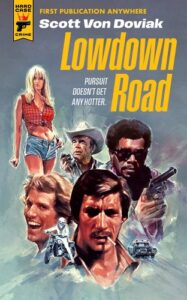

I have described my new novel Lowdown Road (out July 11 from Hard Case Crime) as the ‘70s drive-in movie playing in my mind. In telling the story of cousins Chuck and Dean Melville and their ill-fated marijuana run from Texas to Evel Knievel’s Snake River Canyon event, I draw on a deep well of Americana from the not-so-distant past.

For those too young to remember, there was a time before movies lived on streaming services following a fleeting theatrical release (or none at all). In the early ‘70s, the theater was the only place to see a movie until it turned up on television years later. Films would hang around for months in their first run, and many would resurface later as part of a drive-in double bill. But the drive-in wasn’t exclusively the home of recycled Hollywood hits; American independents were churning out exploitation films specifically geared for rural, often Southern, audiences.

Very often, these “hixploitation” flicks shared a handful of ingredients: fast cars, good ol’ boys gone bad, the Daisy Dukes-clad women who love them, and the redneck sheriffs determined to catch them. Some of these movies featured just enough excitement to fill a two-minute trailer, while others toyed with the formula enough to be memorable.

The year 1974 was a particularly fertile one for this type of entertainment. Though it boasts name actors in Peter Fonda, Susan George, and Vic Morrow, the true stars of Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry are the vehicles, in particular the 1969 Dodge Charger our outlaw anti-heroes use to flee the cops after extorting $150,000 from a supermarket manager. The film has little going for it besides automotive mayhem; the script is mostly witless banter as Fonda and George exchange insults that sound like placeholders for the real dialogue that was never written. Its most memorable moments come in the last reel. Those who recall how Morrow met his end on the set of Twilight Zone: The Movie will find the scene in which he rides shotgun in a dangerously low-flying helicopter more than a little queasy-making, while the nihilistic final shot feels like the hammer coming down on whatever remains of the ‘60s counterculture.

A much more polished outing the same vein, The Sugarland Express suggests an alternate path for ‘70s cinema had its director stuck with the highway-bound thrills of this film and the TV-movie that preceded it, Duel, rather than inventing the modern blockbuster with Jaws. Goldie Hawn and William Atherton star as the Poplins, an outlaw couple who take a patrol officer hostage as they race across Texas to spring their child from foster care. Spielberg populates the movie with authentic Lone Star faces and locations and wrings a great deal of humor out of the premise before things turn dark in the end. He subverts the expectations of a chase picture as the pursuit turns into a slow crawl toward its final destination.

The independently made Macon County Line is probably best remembered for turning The Beverly Hillbillies’ lovable chucklehead Jethro Bodine (co-writer/producer/actor Max Baer Jr.) into a malevolent redneck sheriff bent on misguided revenge. What’s fascinating about it is that this plot doesn’t emerge until the last 30 minutes of the film. For its first hour, Macon County is a hangout movie paced like an old man sipping iced tea on the porch on a hot summer day in Georgia. Brothers Chris and Wayne Dixon (played by real-life siblings Alan and Jesse Vint) are joyriding around the 1950s south before returning to military service. They pick up pretty blonde hitchhiker Jenny (Cheryl Waters), but their car breaks down in a backwater town where they meet the acquaintance of Sheriff Reed Morgan (Baer).

Menace slowly seeps into the movie. Morgan seems genial enough at first, but the mask keeps slipping. He’s not happy that his son has started playing with black kids after school. He harasses Jenny and the Dixons at the gas station where they stop for repairs, seemingly for no other reason than that they’re from somewhere else and he’s bored with maintaining law and order in his sleepy town. But that town gets a wake-up call when two real criminals tear up the highway, and when Morgan’s wife is raped and murdered, the sheriff assumes the innocents he pushed around earlier are to blame. This supposedly true story (as so often in these cases, it’s not) becomes a horror movie in its final minutes, building to what must have been a shock ending at the time, but feels inevitable now.

By the year of our nation’s Bicentennial, the good ol’ boy formula was well-worn enough to deserve a feminist rebuttal. The Great Texas Dynamite Chase is right up there with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in the annals of “Texas-based film titles that tell you exactly what you’re going to get.” Two young women go on a crime spree, robbing banks across the Lone Star state with sticks of dynamite. By the time they pick up a denim-clad boy-toy, you may be thinking this all seems familiar, and indeed you wouldn’t be the first to notice the similarities to the later, slightly higher-budgeted movie Thelma and Louise. Dynamite Chase doesn’t boast the star power of that film, but it does have secret weapon Claudia Jennings, the queen of the hick flicks, who tragically died in a car accident just a few years later.

The hixploitation trend reached its apex the following year with the release of Smokey and the Bandit, a movie that transcended its drive-in roots by becoming the second highest-grossing movie of 1977, right behind Star Wars. Technically Smokey qualifies as a crime movie, even if the transportation of Coors beer from Texas to Georgia is the lowest stakes crime imaginable. (It was illegal at the time!) It’s all played for laughs, with Jackie Gleason transforming the menacing redneck sheriff into a blustery figure of fun with toilet paper stuck to his shoe, and thanks to the chemistry of the cast, it still goes down easy all these years later. (The less said about the sequels, the better.)

For a time during the pandemic, a drive-in movie comeback seemed plausible, but now we find ourselves in a world where automotive mayhem on the big screen is the domain of the billion-dollar Fast and the Furious franchise, not disreputable, scrappy independents. The good news is that most of these cheap thrills of yesteryear can be found on anything-goes streaming services like Tubi. The drive-in has come home, which isn’t entirely a bad thing. Have you seen the price of gas lately?

*