The Knapp Commission into corruption in the New York City Police Department started public hearings on October 19th, 1971. Established by then mayor John Lindsay, the proceedings were televised live on public television across the five boroughs of New York and covered in the print media. The Commission’s final report, handed down in December 1972, was damning. Months of testimony from low level pimps and narcotics dealers who paid regular bribes to the police in return for protection, to police whistleblowers, and the flamboyant escort and madam Xaviera Hollander, revealed that the city had a sixth organized crime family in addition to the Gambino, Lucchese, Genovese, Bonanno, and Colombo operations: the NYPD. Police corruption was systemic and pervasive, including shaking down gambling, narcotics, loan sharking, and prostitution operations, the proceeds from which were distributed from ranking officers to foot patrolman. The situation was particularly bad in the city’s Black neighbourhoods, where the still overwhelmingly white force extorted businesses – legal and illegal – backing up this graft with violence and brutality.

But when the Commission’s report was released, the police denied any wrongdoing. Then police union president Robert McKiernan gave a press conference in which he dismissed the report as “a fairy-tale, concocted in a whorehouse and told by thieves and fools.”

One person who had clearly been following the Commission was the Philadelphia-born, Lower East Side of Manhattan raised film director, Sidney Lumet. It is no coincidence he bookended 1973 with two incredibly gritty police neo-noirs. Released in the US in December 1973, Serpico was the first of a quartet of films directed by Lumet – the others being Prince of the City (1981), Q&A (1990) and Night Falls on Manhattan (1996) – that chronicled the changing face of New York and corruption in its police force. The second, much lesser known film, which premiered in London at the beginning of 1973, was the US/UK co-production, The Offence. While on one level very different films, set on two sides of the North Atlantic, both delved deeply into the underbelly of police corruption and brutality. Both contained portrayals of individual law enforcement officers pushed to the edge of their sanity by the harsh reality of their jobs. And both can be seen very much as filmic responses to the avalanche of police graft and abuse of power revealed by the Knapp Commission.

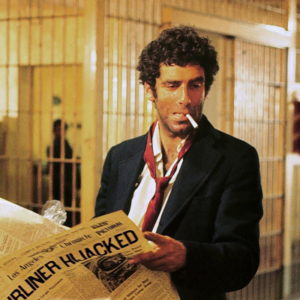

By far the best known of the two films, Serpico was based on the real-life story of police whistleblower Frank Serpico, played by Al Pacino. It opens with Serpico having just been shot in the face during a raid on a suspected drug dealer in Brooklyn and being raced to hospital in the back of police squad car. As news of the incident spreads, one policeman says to another, “Think a cop did it?” The other responds, “I know six cops said they’d like to.” Lumet then moves the story back to Serpico’s police graduation ceremony in the late 1950s. A blue collar migrant boy made good, Serpico is idealistic, and determined to advance in the force. He studies finger printing and learns Spanish after hours. He also does ballet, reads literary novels and, working undercover in vice and racketeering, dresses like a hippie. He’s considered “a weirdo cop” by colleagues and a closet homosexual by one commander. But most alarming to his police colleagues, Serpico will not accept corrupt payments. As one of his partners says, “Let’s face it, who can trust a cop that doesn’t take money?” Serpico moves between precincts only to discover each is as corrupt as the last. He tries to ignore the corruption, work around it, and when he cannot deal with it any further, reports it to his superiors, who do nothing. Eventually, Serpico has no choice but to go to the media, resulting in a front-page The New York Times story on widespread NYPD corruption. It draws national attention and helps instigate what would become the Knapp Commission. Although never conclusively proven, Lumet’s depiction of Serpico’s shooting makes it clear that members of the NYPD set him up to be murdered. Serpico recovers from his wounds and is shown giving public testimony to the Commission. He resigns from the police and a title card at the end of film says: “Serpico is now living somewhere in Switzerland.” He only returned to the US in 1980 and has since continued to speak out against police corruption.

The Offence opens with a slow-motion sequence of uniformed officers rushing into a police interrogation room, where veteran plainclothes detective, Jackson (Sean Connery), has just inflicted a brutal act of violence on a suspect he was interrogating. As panic ripples throughout the station, Jackson can be seen mouthing the words “Oh my God,” as he realizes what he has done. The film flashes back to earlier that night. Jackson is part of an investigation into a series of abductions and sexual assaults of young girls living around an anonymous outer suburban London housing estate. Another girl has just been taken and is found by Jackson, but not before her unknown assailant has molested her. Frustrated by their lack of progress, the police pick up a man drunkenly wandering around the terrified town after dark. The man, Baxter (Ian Bannon), professes his innocence, but also exudes a weird vibe that makes his claims not entirely believable. Jackson is convinced Baxter is the attacker and takes it upon himself to extract a confession, eventually beating the suspect so hard, he is hospitalized and dies. The narrative shifts between the interrogation and the repercussions flowing from it. During the interrogation, Jackson and Baxter play a game of psychological cat and mouse, the policeman finally snapping when Baxter goads him with the suggestion that his obsession with the sexual assault of young girls is motivated by far darker urges than he will publicly admit to. In the wake of his actions, Jackson confronts the reality of his disintegrating marriage, a harrowing scene with his long-suffering wife, Maureen (Vivien Merchant), and is investigated by a stern internal affairs officer called Cartwright (veteran British actor Trevor Howard). Cartwright appears sympathetic to Jackson but also pushes him hard to come clean about what happened. Jackson, in turn, fluctuates between justifying his actions and being terrified of what he has done and the consequences.

Worried he would be typecast, by the early 1970s Connery was keen to move on from the role of James Bond. United Artists offered him two million dollars to make two films of his choice in return for reprising the role of 007 for the sixth entry in the franchise, Diamonds Are Forever. Connery’s first choice of project was a tough police procedural based on a 1969 play by John Hopkins, This Story of Yours. Lumet, whom Connery had enjoyed working with on The Hill (1965) and The Anderson Tapes (1971), was brought in to direct. But audiences had grown used to the Scottish actor as the suave, globetrotting spy and were not impressed. The Offence was a critical hit but a commercial flop which took years to recoup its modest budget, and United Artists managed to wheedle out of its commitment to fund Connery’s second project, a version of Macbeth that he would have directed. The Offence still languishes in relative obscurity in Connery’s filmography, which is a pity because it is arguably one of his best performances. A disjointed, surreal journey into the darkest recessing of policing in which little is as it seems, Jackson literally unravels on the screen, eaten to the bone by the terrible things he has witnessed on the job, which are hinted at in flashbacks. Whether Baxter was guilty is never made clear. Jackson’s fate and the inference that perhaps he harbours darker urges of his own, is also unresolved.

Serpico, by contrast, was a major critical and commercial hit. The film tapped into a post-Knapp Commission feeling of dissatisfaction with law enforcement. Ultimately, however, Serpico’s success fed off much deeper cultural currents. As Sven Mikulec wrote in an article on the site Cinephilia and Beyond: ‘The United States was plagued by the Watergate scandal, a punch in the face that left a lot of Americans with the need to reexamine themselves and their faith in the government and the rule of law. It’s not difficult to imagine why a story of an honest, dedicated police officer rising against the corrupt system would ring inspiring to an average moviegoer.’

The film was a difficult shoot for Lumet. Producer Dino De Laurentiis had fired the original director, and Lumet was parachuted into the production only weeks before principal photography was scheduled to begin. The script, based on a book by journalist Peter Mass, was still in draft form. There were over a hundred speaking roles to cast, with Pacino only coming on board quite late, and locations were yet to be selected.

Serpico is not without its issues. The story is somewhat sprawling and overlong. Critics have also taken aim at the fact that Serpico’s girlfriends, played by Barbara Eda-Young and Cornelia Sharpe – relationships that are both ultimately destroyed by the pressure of his police work – are very underdeveloped as characters. But Serpico has major strengths. Lumet’s knowledge of New York helps imbue the film with an intense street level realism. This aspect was, ironically, also assisted by the NYPD, which keen to recover some of the massive public relations ground lost due to the Knapp Commission, cooperated with Lumet, allowing him to shoot in four live stationhouses while police work went on in the background. Pacino delivers a stunning performance, literally transforming in character and appearance over the course of the film, as his struggle gradually warps him, physically and mentally. Key is the mounting sense of isolation Serpico experiences and the gradual realisation of the physical danger he is in by virtue of being a whistle blower.

Fifty years after its release, Serpico still packs powerful dramatic punch as the story of a lone individual determined to do whatever it takes to bring down endemic police corruption at any cost.