One of the things that has always fascinated me about history is those individuals who just, by the narrowest of margins, miss out entirely on fame and fortune. The scientist pipped to the post by a rival in another country. The writer whose forthcoming book is identical in theme to one that has just been published to massive acclaim. Even the space race! All of history is littered with examples, both large and small, of intriguing also-rans.

When I first came up with the idea for The Gifts, my debut adult novel, set in Victorian England, I knew I wanted it to focus both on the lives and experiences of women, but also on the sort of figures who get forgotten about in history books. Those who aren’t ‘the first’ but who might nudge the door open for those who follow later. I assembled my cast from them: a female botanist who is viewed as a hobbyist; a young woman with a talent for writing at a time when female journalists did not yet exist; a storyteller who weaves tales from her own imagination; and a gifted artist whose surgeon husband’s streak of ruthless ambition comes to threaten all their lives.

Whilst everyone knows of Charles Darwin and his theory of evolution, published in 1859, fewer know of Alfred Russel Wallace who was theorizing on the same ideas around the same time. A brilliant and fascinating man in his own right, Wallace has long since faded into the background. Likewise, so has someone from even earlier—John Hunter. An 18th century anatomist and polymath, famed in his lifetime, he was a superb surgeon possessed of a truly inquisitive mind. Admired and feared in equal measure, he acquired his bodies for dissection through illicit means, and his grand London house with its back entrance into the basement was even the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde. Hunter was a gifted naturalist and his observations on geology and the wildlife he saw and studied meant that he too was already thinking about ideas around evolution some sixty years before Darwin published. Hunter never made his ideas public and no wonder, for even when Darwin was brave enough to publish, the reaction was explosive. In a period in which Christianity dominated all aspects of daily life, to question how life itself was created was, in essence, to question not just the veracity of the Bible but the word of God himself.

For me, those six decades between Hunter standing by the edge of a gorge and pontificating on the true age of the world to the publication of On The Origin of the Species felt exactly the right time in which to set my tale. A time in which the hand of God was to be felt in every event, in which success was seen as virtue, and in which religion dominated every element of society. What better period than in this hotbed of ideas to set my tale in which, I confess, one of my female characters grows wings? How might the impossible be viewed and who might wish to take advantage of it?

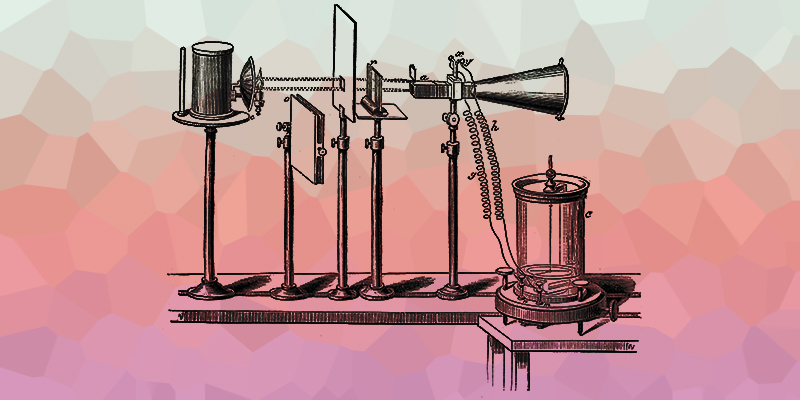

I am, of course, a storyteller and not an historian and the important thing for me was that the world of the book felt real. Jackdaw-like, I chose the shiniest and most interesting real-life snippets and nuggets for my tale from across different years. As my delving into the past continued, I came across the Victorian surgeon Astley Cooper. A brilliant man who ended up working directly for the Queen herself, he was incredibly arrogant in his youth with an almost cock-sure belief in himself. His ability, as a surgeon, to save or destroy a man’s life with a slice of a knife offered power and prestige but it offered something else too, for surely the ability to hold life or death in one’s own hands was dangerously close to the power of a god?

In contract to Cooper was the famed novelist George Eliot, aka Mary Ann Evans, who started to question her own faith around this time—much to her father’s dismay. To placate him and save ‘face’, she agreed to continue attending church with him but refusing to listen to a single word. A very English compromise and one I stole directly for my botanist character Etta.

England in 1840 was a heady time. Change was in the air and that conflict, between science and religion, was already present. Darwin became the catalyst, the light held to the touchpaper in an explosion of ideas and outrage that changed society and culture in ways that still resonate today. I wanted to reflect that simmering sense of change and conflict before the paper was lit, the way perceptions were already shifting, the dedication and devotion of ‘men of science’ at a deeply religious time. I wanted to explore the morals of it too—what might someone do in the name of their beliefs and in the name of science? How far might they go? Edward, my surgeon character, when faced with a winged woman, thus finds himself torn. He considers himself a deeply moral man and yet he uses his belief in both religion and science to justify his actions, no matter how abhorrent.

The great British zoologist and thinker Desmond Morris famously called humans ‘the artistic ape’, a brilliantly compact phrase with a nod to Darwin that beautifully sums up the compelling desire in humans to create something that did not previously exist. A work of imagination. A red outline of a hand in a deep, dark cave. A story woven from words told by the fireside. An idea for a brand new scientific experiment. A ‘what if’.

It always makes me think how we are, in essence, storytelling apes too, creating myths and legends to make sense of the world around us, and The Gifts is my own small contribution to this ancient urge and tradition. I think there’s a deep need in all of us to want to believe in something, whether it is a spirit or a god, a ghost or a superstition, to look up to the stars and imagine something bigger and brighter than ourselves. Yet whatever our belief, we must be careful what we do in its name, as my character Edward demonstrates. As Hippocrates said ‘do no harm’ and a plea for tolerance in our own modern and equally divided world is surely no bad thing.

***