Glen S. Miranker has what he believes to be the best Sherlock Holmes collection in private hands. No matter that he narrowly lost the most recent manuscript leaf from The Hound of the Baskervilles when it sold for $423,000 at auction this past November—he already owns three. Plus four complete manuscripts of Arthur Conan Doyle’s short stories, all of the British and American first editions, relevant magazine serials, numerous original illustrations, letters, theater and film ephemera, and even a set of souvenir spoons. All told, the collection contains about 7,000 items.

“It’s not a competition,” he says. “It’s a passion.”

Miranker, a retired Apple executive, exudes affability as he discusses the publishing history of the Sherlock Holmes juggernaut and his own ‘gentle madness’ in pursuing it all.

“Normal, well-adjusted people don’t collect books,” he quips, while standing outside New York’s Grolier Club earlier this month, taking a break from installing the first major solo exhibition of his collection, on view at the club through April 16. Sherlock Holmes in 221 Objects—the 221 is a nod to the fictional detective’s Baker Street address—was co-curated by his wife, Cathy, who purchased, for $25, the book that sparked Glen’s interest in all things Sherlockian more than forty years ago.

“A substantial part of the enjoyment is unearthing the stories behind my books,” Miranker says. The Hound manuscript pages, for example, are literary survivors. On April 15, 1902, Conan Doyle’s Hound appeared in the U.S., bringing word of Sherlock Holmes after a seven-year hiatus. It was an instant hit, selling 50,000 copies in less than two weeks. An unusual publicity stunt cooked up by the publisher, McClure, Phillips, & Co., may have spurred those sales—they broke up the original manuscript, essentially destroying it, and distributed individual sheets to bookstores for display. Of an estimated 185 pages, only 37 remain.

The Hound is Miranker’s favorite Sherlock novel, and the three manuscript leaves he has thus far acquired are, in his opinion, the most powerful items in his collection. “I just find that reading something in Doyle’s hand just completes, for me, emotionally, the transformation, the transmogrification of me back into Victorian times and back in London. And I know I can’t explain it, but it’s a very real and wonderful feeling,” he says.

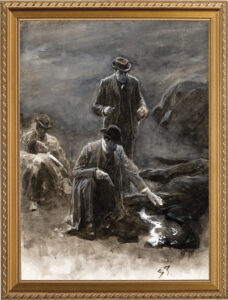

As on Conan Doyle’s moors, the titular hound looms large in the exhibition and the illustrated hardcover catalog. This is perhaps nowhere more evident than in the original illustrations made for the various magazine serials and book editions. So many artists have taken a crack at the part bloodhound, part mastiff, that sometimes the dog is depicted as a dopey Labrador and sometimes a fire-eyed wolf. (The pen-and-ink illustration by John Holder that is used on the front cover of a 1981 Penguin Books paperback is a dead ringer for Zuul from Ghostbusters.) British illustrator Sidney Paget, who illustrated 37 of Conan Doyle’s short stories and the Hound, created not only the iconic look for the detective but for the canine as well, says Miranker. “I think a Paget hound is certainly pretty frightening and also quite realistic.”

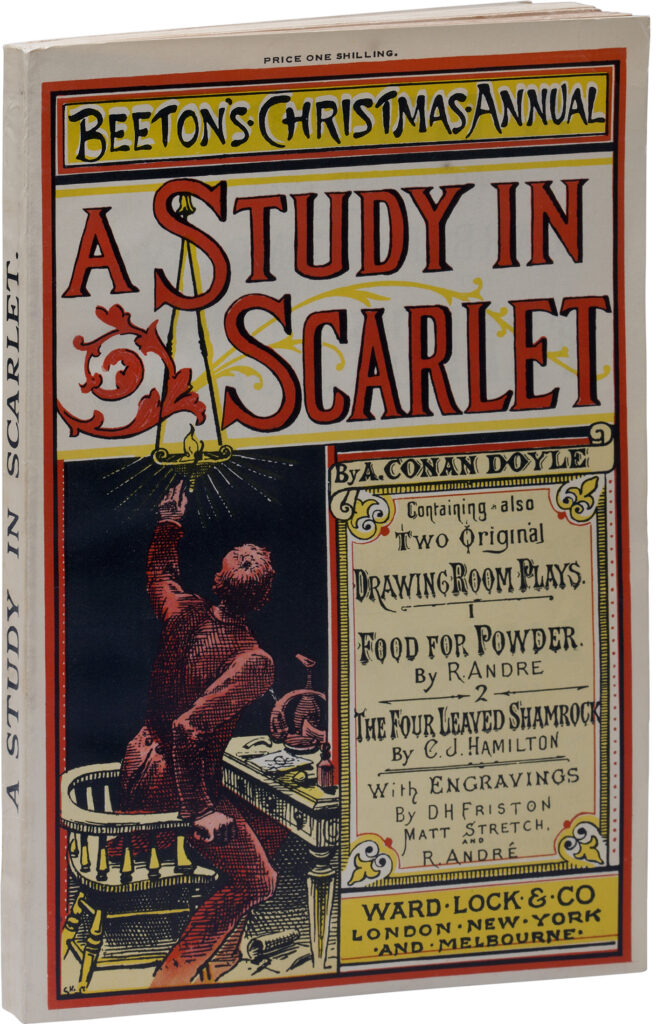

Three publishers rejected Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel, A Study in Scarlet, before the author finally placed it in Beeton’s Christmas Annual in 1887. Readers loved it, and the journal sold out before Christmas. The author, however, “got burned,” in Miranker’s words, by the publisher, who had offered a flat “£25 for the complete copyright.” So while this first Sherlock tale took off in reprints, Conan Doyle didn’t make another dime from it.

Today, this magazine with its flashy cover and claim to fame, is a rarity. According to Miranker, “just 34 copies are known, only 13 are in private hands, and only 11 are complete.”

Doyle learned a hard lesson about copyright (see above) and became much more savvy about retaining his rights. He didn’t yet have an agent for these negotiations, and when he secured A.P. Watt for that purpose a few years later, it “relieved me of all the hateful bargaining,” he wrote in his memoir.

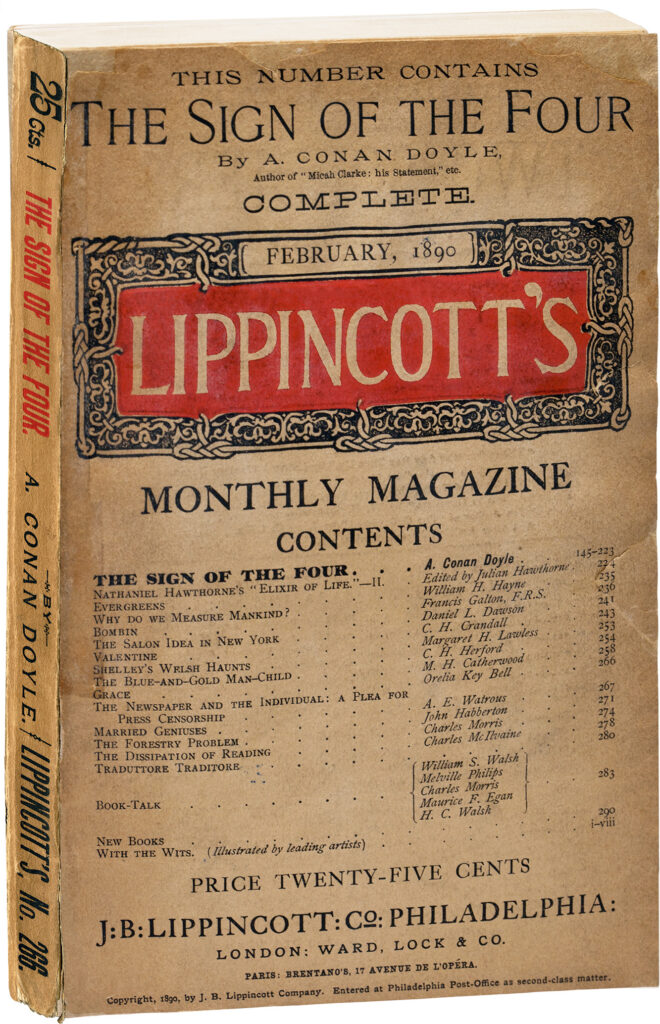

The publication of his second novel, The Sign of the Four, was more fortuitous, at least initially. Conan Doyle had been invited to a dinner in August 1889, where the guests included Oscar Wilde and Lippincott’s editor. That evening, both he and Wilde were commissioned to write novels, and both appeared the following year: Doyle’s The Sign of the Four in February and Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray in July.

But then pirate publishers took the lead. Published before the 1891 U.S. Copyright Act, The Sign is the most pirated Sherlock novel, according to Miranker. In his library, he has copies published by 49 different American pirate publishers. Piracy has become a specialty; his friend, antiquarian bookseller Peter Stern, who wrote the afterword for Miranker’s catalog, calls it “a vast, unexplored area, frustrating, obscure, derided, and ignored….” By digging into the provenance and bibliographic history of pirated editions, Miranker says, he can make some major contributions to Sherlockian scholarship.

Sherlock Holmes in 221 Objects at the Grolier Club

Sherlock Holmes in 221 Objects at the Grolier ClubFrom the Collection of Glen S. Miranker

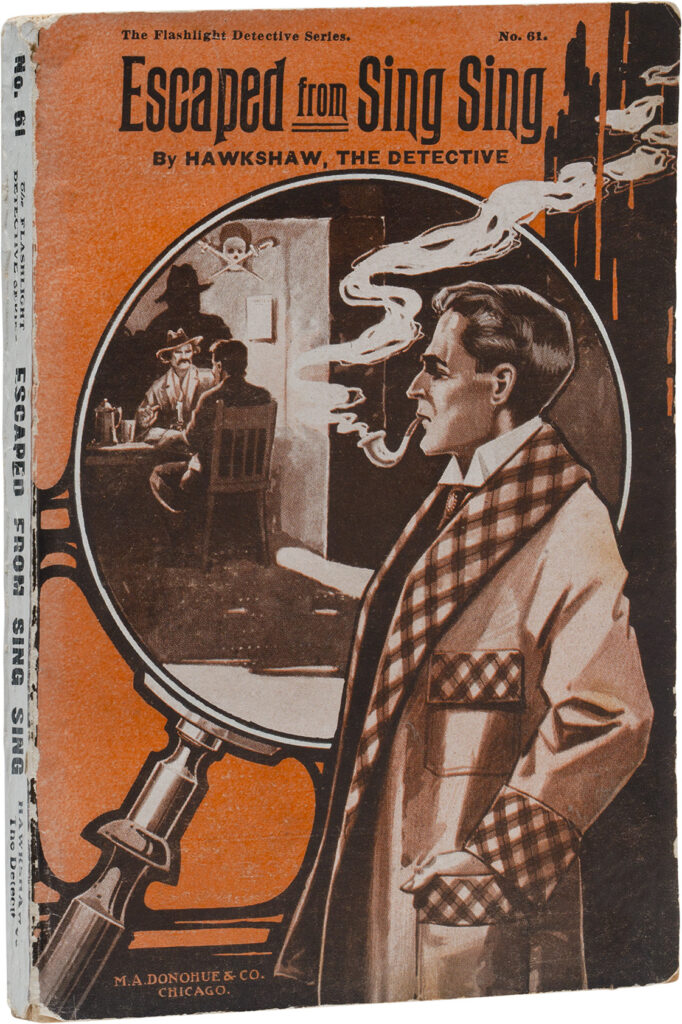

Escaped from Sing Sing, an undated Sherlock lookalike published in Chicago, is not a piracy, although a solid case for intellectual theft of Frederic Dorr Steele’s cover illustration might be made. Labeled No. 61 in The Flashlight Detective Series, the book has “a Sherlockian look but nothing Sherlockian inside,” writes Miranker in his catalog. Aside from the cover, his interest in this paperback stems from the novel’s setting in Ossining, New York, the collector’s hometown.

While pulpy paperbacks and piracies occupy an important part of Miranker’s collection, he has also acquired, over a thirty-year period, four manuscripts that approach ‘holy grail’ status.

Conan Doyle was done with Sherlock by 1893 and famously sent him cascading over Reichenbach Falls to his supposed death. But his fans wouldn’t relent, and his mother was unhappy about it, too. So when Collier’s Weekly offered him $45,000 to revive the detective in thirteen short stories, he picked up his pen. The stories would come to be published in book form as The Return of Sherlock Holmes (1905).

“The Adventure of the Dancing Men,” written circa 1903, was the third in the sequence. Miranker bought the manuscript at auction in 2018 for $312,500.

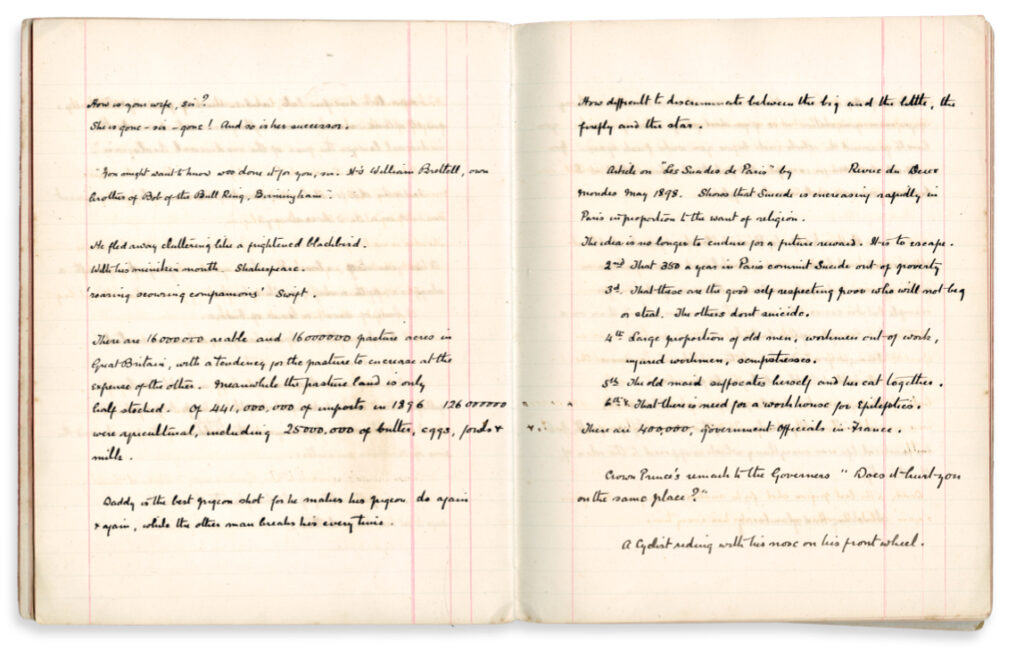

From 1885-96, Conan Doyle kept a fifty-page ‘ideas’ journal and calendar, known as the Norwood Notebook. It is here that he dashed off the earth-shattering entry, “Killed Holmes,” in 1893, followed years later by a quick jot about a walking stick and a St. Bernard, which any Sherlockian will recognize from the opening of the Hound. There are also “thoughts about religion, poetic fragments, descriptive phrases, quotations from his reading, and snippets of dialogue,” notes Miranker.

Presented in this exhibition alongside letters to and from Conan Doyle’s literary agent authorizing foreign editions or cheap reprints of Hound, the notebook becomes one of a “constellation” of objects that elucidate the book’s history. “You can see the physical life of the story of the book as it evolves from an idea in a notebook to establishing markets for it,” says Miranker. “That’s what I like to do.”

All Images Courtesy of Glen S. Miranker