I always feel a bit guilty when I discuss movies in an essay about writing—movies are the cheap version of entertainment, right? They’re easy, shallow, a 90 page screenplay is nothing compared to churning out ninety thousand words. Except, having written screenplays I know that they are not easy, or shallow, or quick, and also that to me, my book is a movie. It plays in my head as I’m writing each scene. I know the set, the lighting, the camera angle behind every word. Storytelling is storytelling—the same rules always apply.

So let’s discuss some movies.

We’ll start with The Ring, the 2002 remake of the Japanese film. Naomi Watts stumbles onto a videotape which, if you watch it, you will die in seven days. Does that not sound like the most ridiculous plot ever? Let’s resolve the issue in the first five minutes: don’t watch the tape. I would never have given this flick a look if it had not been recommended by someone whose opinion I trust, and I’m glad I did. Not only was it scary enough to give me nightmares (no easy feat), it is an excellent example of how a writer can take the most outlandish, far-fetched, more or less laughable idea and if they set up the foundation and take care with the details, the results become not only plausible but inevitable.

Then there’s The Usual Suspects (a bit of a cheat because it’s not really scary). Ah, the unreliable narrator. Before there was Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train, The Woman In the Window and who knows how many others, there was Keyser Soze. What are you left with when the person you’ve been listening to the entire time turns out to have been lying about every. single. thing. The questions burrow into your brain and churn forever. Was it everything? Was any of it true? You’ll never stop wondering.

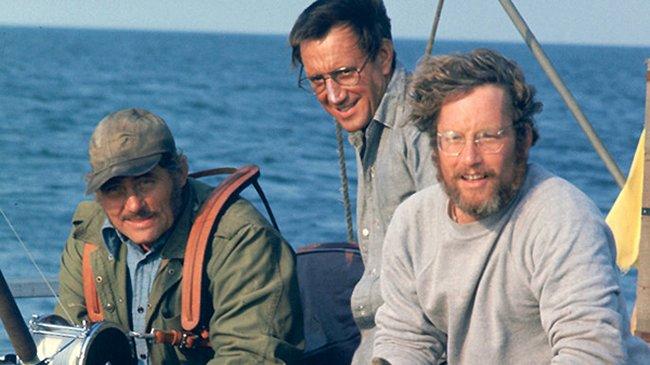

Jaws provides a classic example of how what you can’t see is scarier than what you can. In those dark ages before CG, if Steven Spielberg wanted a menacing Great White to follow directions he had to have one built, a mechanical device that could swim underwater via remote control but still look like a real shark. An electronic device functioning under water…yeah, that had issues, enough to hold up filming so that Robert Shaw and the rest of the crew got to sit around in Edgartown (Martha’s Vineyard) and drink while—being still being paid. To stop wasting money Spielberg had the characters shoot the monster with yellow barrels, so…you can’t see it, but you know it’s there. Those barrels pop out of the water, and sweat pops out of your pores.

Happy Death Day seemed like a bit of teenage fluff, saved only by the irrepressibly snarky protagonist and the grafting of a murder mystery onto a Groundhog Day ripoff. But every movie is a makeover movie in some respect—after all, a cardinal rule of storytelling is that the character has to change between the first page and the last because of things that happen during the in-between. The day resets each time Teresa is murdered, so while trying to break the cycle she resets everything else as well, from figuring out the killer and making peace with her parents down to choosing the nice boy over the popular one and shutting down the fat-shaming of a hapless classmate. This movie took the cardinal rule and ran it out to the nth degree.

If you’re prone to seasickness you may have not reached the end of The Blair Witch Project, but take it from me, it was a brilliant, punch-to-the-gut example of misdirection that I try to use in every book I write. No unreliability here, the movie fairly and honestly informs you of the real threat near the very beginning—but after sitting through ninety minutes of potty-mouthed teenagers wandering around lost in the woods, you have completely forgotten that warning. Not until the final moments does that information jump screaming into your consciousness…and by then, of course, it’s too late, and the characters are snuffed out with a blinding speed that steals our very breath as well.

Which is exactly how we want our readers to feel.