I’m an old-fashioned writer at heart. I like my martinis dry, my women wry, my plots chronological and my crimes supernatural. I don’t want to read about heads kept in a Milwaukee fridge, or bodies buried in the crawl spaces under a clown’s house, or bloody mayhem inspired by the Beatles tune, Helter Skelter. (I didn’t even like the song.)

On those rare occasions when I’m exposed to such stuff, there are moments I feel weirdly complicit—I am immersed in, and even tacitly enjoying, a story in which real people have suffered unimaginable horrors. That stuff really happened.

But when I read, or for that matter write, books in which crimes of a supernatural nature occur, I can take comfort in the fact that no, these things did not ever really happen, no, I am not exploiting anyone else’s real anguish, and no, the vampire didn’t really drain the life out of some nubile maid, the werewolf didn’t really rip someone to shreds.

Crimes in a supernatural story have other things to recommend them, too—they’re less predictable, more far-ranging, unrestrained by the laws of everything from gravity to mortality. In some of the most iconic and revered supernatural tales of all time, the crimes committed are already far removed from us in time, and even further removed from the time-frame of the books themselves, involving sins of the fathers coming home to roost, or tortured ghosts still unable to go to their rest until their bad behavior in life has been expiated (think of poor Marley in A Christmas Carol). To wit, I cite a half dozen of the most famous and influential supernatural novels and the intriguing, even unique, crimes central to their cores . . .

Bram Stoker, Dracula

Crime: Ex-sanguination

Published in 1897, after a long and agonized parturition on the part of its author, Bram Stoker, the book met with generally good reviews, but a fair amount of criticism, too, in part for its lurid passages of blood-letting and, to be blunt, blood-sharing. Try re-reading the scene in which Jonathan Harker lies insensate on the bedroom floor as his wife kneels on the bed, her mouth pressed to an open wound in the vampire’s breast, sucking his blood as he holds her head fast. Kinkiness, thou hast no better example, and even in the Victorian age (maybe especially in the publicly-repressed Victorian age) the metaphorical implications were not entirely lost. The novel didn’t really take on a life of its own and become the mythic tale the world now knows until 1922, when F.W. Murnau made the film adaptation, “Nosferatu.” Stoker’s widow sued for copyright infringement, and won, and all the copies of the film were supposed to have been destroyed. Thankfully, one or two slipped through the net. And when Bela Lugosi came along almost a decade later, with Universal Pictures behind him, Dracula was cemented into the collective human consciousness in a way rivaled only by one other. See directly below.

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

Crime: Grave-robbing and desecration of human remains

To this day, I am astonished when I think of Mary Shelley, 19 years old, marooned in the Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva in Switzerland, during a hellish spell of stormy weather, coming up with a story – on a dare! —so spooky, so powerful, so resonant on so many levels. It was Lord Byron who suggested to his houseguests that they while away the time by trying to write a ghost story that they could then share with the others around a roaring fire, but it was only Mary, after hearing a discussion of galvanism, who was inspired enough to pick up the ball, run with it, and create a masterpiece in the process. (Although Dr. John Polidori, another houseguest, was inspired to write The Vampyre, his work can’t hold a candle to Shelley’s.) And please, you have to forget the hulking, mumbling monster portrayed by Boris Karloff in the movies. Shelley’s creature is imbued with the full range of human emotions and the ability to articulate them eloquently. That’s what lends such poignancy to this otherwise harrowing tale.

Robert Louis Stevenson, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Crime: Identity Theft

Yes, yes, Dr. Jekyll did voluntarily conjure up Mr. Hyde—his evil alter-ego—by imbibing those mad concoctions, but he never expected the villain to take over! At will! Nor could the good doctor have foreseen the global shortage of the peculiarly-tainted chemical he would need to whip up more of the mysterious cocktails needed to remedy his situation. That said, Mr. Hyde is launched on a career of crime and depravity that manifests itself early on when he tramples an innocent girl at night (and buys himself out of the predicament using Jekyll’s checking account) and culminates in the brutal murder of the respectable Sir Danvers Carew, beaten to death with a walking stick. In an interesting coincidence, one which inspired me to write a novel called The Jekyll Revelation, the stage play of Jekyll and Hyde opened at the Lyceum Theater in the summer of 1888, just when Jack the Ripper began his lethal rampage in the East End. If you’re looking for the true identity of the Ripper, look no further—I’ve got a theory, elucidated in the book.

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

Crime: Artistic Representation

Oscar Wilde’s hero, Dorian Gray, commissions a portrait from the society portraitist Basil Hallward that, through a barely-breathed wish from Dorian, takes on all of the subject’s sins (and there are plenty) and ages appropriately; Dorian, meanwhile, remains his youthful, unblemished self, untouched by time or crime. All I can say is, if Hallward set up a studio in Beverly Hills, anywhere near my place, the line would be around the block and all the way down Rodeo Drive. (But who am I kidding? Given what stared back at me in the mirror this morning, I might be in that line myself.) At the time of publication—1890—the book was thought immoral, and that was before its author was convicted in 1895 of even worse crimes (homosexual conduct) and sentenced to two years of hard labor; he survived his imprisonment, but emerged such a broken man that he died destitute, and in virtual exile, in Paris, just a few years later. He was only 46.

Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights

Crime: Mortgage Fraud

Heathcliff, a man so deprived he only gets the one name, uses his ruthless temperament and financial acuity (gained somewhere in the New World, doing something mysteriously lucrative) to wind up as the owner of both Wuthering Heights, where he was at first brought as an orphan, and ultimately Thrushcross Grange, too, the estate where the love of his life, Catherine Earnshaw, once lived as the wife of the aristocratic Edgar Linton. Published in 1847, under Emily Bronte’s pen name, Ellis Bell, the book stirred up a ton of controversy with its dark, Gothic tone, its lonely ghosts wandering the moors, and its implicit challenges to traditional Victorian notions of morality. Why, Heathcliff even sneaks to the side of Catherine’s open coffin to open the locket around her neck and replace a snip of her husband’s hair with a lock of his own. Talk about chutzpah. The English poet and painter, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, had it just right when he declared Wuthering Heights to be “a fiend of a book…an incredible monster…The action is laid in hell – only it seems people and places have English names there.”

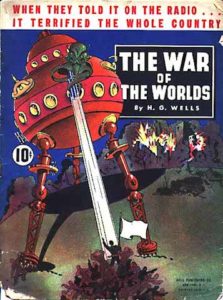

H. G. Wells, The War of the Worlds

The Crime: Crimes Against Humanity

It’s not that the Martians had any personal vendetta against anyone (an ex-wife, a former business partner, an upstairs neighbor who played his music too loud)—they had it in for all of us. H.G. Wells upped the ante in the supernatural scares department when he created the huge, lumbering tripods, on articulated stilts, bucketing across the English countryside and laying waste to everything in their path. In doing so, he helped create a genre—science-fiction—that not only endures but thrives to this day. Extraterrestrial invasions, time machines, invisible men, inhumane practices akin to cloning (see The Island of Dr. Moreau), astronomical catastrophe (In the Days of the Comet), genetically-modified agriculture (Food of the Gods), he virtually mapped out a universe of story ideas that never had to rely on such old, real-life crime staples as bank robbery or car (well, buggy) theft. I can read any of Wells’s stories today and enjoy them for their incredible flights of fancy, without ever once fearing the intrusion of a serial killer or school shooter ripped from the headlines of today’s newspapers. Although it may be cold comfort, supernatural crime, no matter how well or even frighteningly rendered, is essentially bloodless. It never actually happened…yet.