Several years ago I turned to a life of crime.

After a career writing and making comedies of various stripes—sitcoms, rom-coms, satires, dramedies—producers and studios started asking me for screenplays and TV pilots about detectives. I did three of them in a run of five jobs, after never having written any at all in my first twenty years in the business. One of those scripts, a feature screenplay, ended up being reverse-adapted into my first novel, Last Looks.

I have no intention of going straight anytime soon.

It’s not that I’ve abandoned comedy, it’s just that I’m enjoying the hell out of something that movie fans and great filmmakers have known since the silents: that comedy and crime go together like caramel and salt. The tension of crime drama sets an audience up for the unexpected laugh; the distraction of comedy sets an audience up for the unexpected thrill or plot twist.

In fact, the crime comedy is such a staple that it would be hard to make any kind of list of great movies without including a few. I’m sure you’ve got your own favorites; mine would include The Lady Eve, Midnight Run, Miller’s Crossing, The Sting, The Player, and I’m just warming up. But you don’t need me to make that kind of list; you know all those.

Instead I’d like to point you toward half a dozen you might have missed. Some are flawed, but all are worth a watch, or two, or five.

Quick Change (1990)

Bill Murray gives one of the most controlled performances of his early career in his only directorial credit (shared, with Howard Franklin, who adapted the script from a book by Jay Cronley). Murray robs a New York City bank, orchestrating a hostage standoff which would be more reminiscent of Dog Day Afternoon if Murray weren’t in full clown regalia. He outwits police chief Jason Robards and slips out with the money and his two accomplices (Geena Davis and Randy Quaid), intent on getting away for good from the city he’s come to hate, if they can only find their way to the airport. The romantic comedy never really works, but it’s one of my favorite Murray performances, the supporting cast is a who’s-about-to-be-who (including very young Tony Shaloub and Stanley Tucci) and it holds a special place for me as a sort of perverse paean to the last days of the bad old New York, which I left myself only months before Quick Change came out.

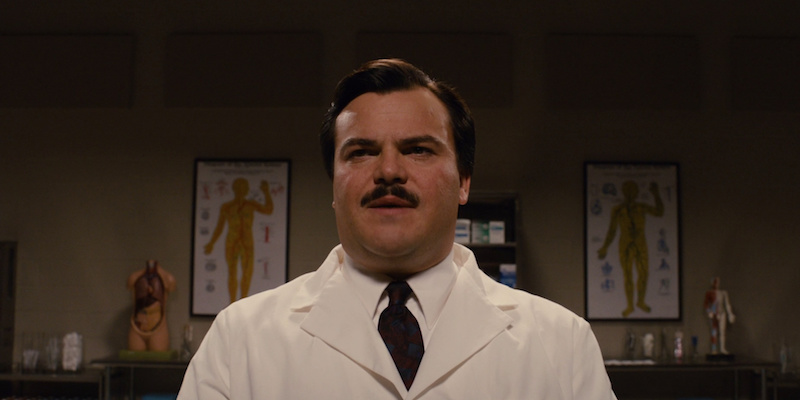

Bernie (2011)

Texas Monthly’s Skip Hollandsworth is America’s journalistic maestro of comedy and real-life crime, and here he joins forces with one of my favorite filmmakers, Richard Linklater, to tell the true story of Bernie Tiede of Carthage, Texas. An astonishingly well-loved assistant funeral director, Bernie takes up with a wealthy widow forty years his senior, becomes her companion and eventually her emotionally abused servant, then kills her, stuffs her in a freezer, and starts giving her money away to worthy causes and neighbors in need. Linklater brilliantly offsets Jack Black, whose chirpy portrayal of the sexually ambiguous Bernie dances on the edge of unreality, with a Greek chorus made up of the actual townspeople of Carthage, who keep the whole thing grounded by sharing warm memories of the killer and less warm memories of his victim (Shirley MacLaine) and prosecutor (Matthew McConaughey). Doubtless some will find the whole enterprise too sympathetic to a confessed murderer, and it certainly invites some larger questions about fact vs. truth and reportage vs. art. The bizarre series of events triggered by the film—Tiede was released from his life sentence to go live with Linklater for a while, and later re-sentenced and returned to prison for ninety-nine years to life—will only add to those conversations.

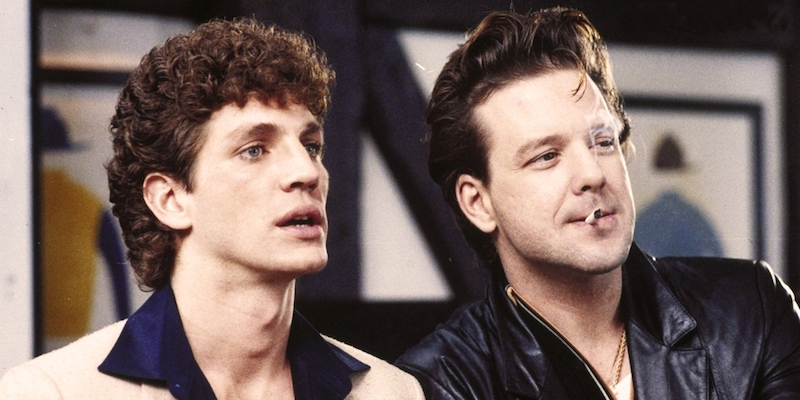

The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984)

Believe it or not, there was a moment when Mickey Rourke and Eric Roberts as your leads meant you had a way cool cast. Directed by Stuart Rosenberg from a script by Vincent Patrick (based on his own novel), it’s about dreamer Rourke and his schemer cousin Roberts, working stiffs with expensive tastes who pull the wrong robbery and pay dearly for it. The dialogue sparkles all the way through (I particularly like an exchange, over a racing form, about what exactly a gelding has removed) and another killer supporting cast, led by the legendary Geraldine Page, whose brief appearance won her an Oscar nomination. Roberts has the flashy role, but it’s Rourke who holds the movie together; every time you’re sure he’s finally going to drop this cousin who keeps dragging him down, he gives Roberts a look of genuine love, and somehow it all makes sense. And about that cool? Check out the stickball scene, with Rourke pitching in a suit, cigarette in hand, swaying to Sinatra’s “Summer Wind,” and the pull back to the wide shot of his whole infield bopping along with him.

Panic (2000)

The first time I saw Panic (written and directed by Henry Bromell), I remember laughing hard. The comedy hasn’t held up as well as I thought it would but the movie’s so wonderful and so extravagantly under-appreciated that I have to include it here anyway. It’s about a depressed hit man (William H. Macy) caught between his psychotherapist (John Ritter) and his boss-father (Donald Sutherland, extra creepy), and also between his wife (Tracey Ullman) and a complicated young woman (Neve Campbell, so compelling here that her limited resume since feels like a minor tragedy). Analyze This and the The Sopranos, both of which landed around the same time, have made this territory a little too familiar; the once-hilarious scene in which Macy’s mother (Barbara Bain) dismisses his dreams of quitting the family murder business, for example, doesn’t play nearly as outrageous at it once did. Still, the everyday human pain is so sharply and wittily rendered that much of the movie feels like its own flavor of sad comedy, especially several remarkable scenes between Macy and his six-year-old son (David Dorfman), dialogues in long, single shots that feel absolutely real but hit points which give away that they had to be scripted; I can’t imagine how Bromell pulled them off with an actor that age.

The Guard (2011)

In this Irish film written and directed by John Michael McDonagh, Brendan Gleeson tears it up as a profane, politically incorrect and mildly corrupt cop. He’s winding down his career in a comfortable low gear, taking breaks from the job for a drink or a visit with a prostitute or two. Then his young partner gets shot down and he’s slowly overtaken by a sense of purpose which surprises even himself. The whole thing kicks into gear when it morphs into a buddy movie supreme, with Don Cheadle in a rare turn as the straight man, a fish out of water FBI agent sent to the wilds of Galway to stop a looming drug deal. Cheadle’s deadpan, nonplused responses to Gleeson’s unabashed racism (“I thought black people couldn’t ski. Or is that swimming?”) take out the sting and lock in the funny, and when Cheadle says “You know, I can’t tell if you’re really motherf***ing dumb, or really motherf***ing smart,” he’s only a half step behind us, and you know he’s about to catch up.

In Bruges (2008)

It’s Gleeson again in another violent, literate buddy comedy, this one by McDonagh’s more celebrated brother Martin. It’s a stone cold masterpiece and I’m certain the only thing that kept it from being more widely seen and appropriately celebrated is its sole misstep: a lousy title. A team of hit men is dispatched to the well-preserved Belgian city of Bruges to await further instructions after a job gone awry. This time Gleeson plays the seasoned veteran, constitutionally built for patience and to quietly enjoy the tourism opportunity until they’re told what comes next. His rookie partner (Colin Farrell) is miserable, though, immune to the locale’s medieval charms and haunted to the edge of suicide by a tragic mistake. McDonagh keeps the violence offscreen and the comedy light for a daringly long while, using the time to build our investment in the characters and their investment in each other. A flashback to Farrell’s horrific error gives the movie a sudden weight, and the appearance of their rage filled boss (Ralph Fiennes) a sudden tension. The comedy gives way entirely to suspense and then to violence; along the way what first plays as an erudite confection evolves into a blood-soaked meditation on loyalty, honor, debt, and the value of life. It’s the blend of comedy and crime at its most sublime.