I subscribe to Alfred Hitchcock’s theory of suspense versus surprise. Mystery, he said, is when the spectator knows less than the characters in a movie. Suspense is when the spectator knows more than the characters.

Hitchcock’s example involved a box under a table. The box explodes. The audience is surprised. Now let’s imagine the audience knows there is a bomb hidden in the box.

“In these conditions, the same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: “You shouldn’t be talking about such trivial matters. There is a bomb beneath you and it is about to explode!” he explained.

Sometimes fans ask me if I worry that readers will figure out who the baddie is in one of my stories, if they will guess the ending. But I gravitate towards suspense, towards that ticking bomb that we know is under the table. Like Hitchock said, you can surprise someone for fifteen seconds. But you can keep them in suspense for fifteen minutes.

One of my favorite Hitchcock films is Shadow of a Doubt, an undoubtedly Freudian story about a young woman and her uncle. We know from the beginning that the uncle is a serial killer. But you’ll still bite your nails and squirm as you hope the young woman will figure out the truth before it’s too late.

I had Shadow of a Doubt and other Hitchcock films in the back of my mind when I was structuring The Bewitching so I figured I’d talk about five other movies that novelists should watch, which exemplify the principles of suspense.

*

Fritz Lang, M (1931)

Fritz Lang’s tale of a city terrified by a serial killer targeting children makes wonderful use of sound and photography to show us both the police officers searching for a murderer, and the denizens of the underworld who are also intent on catching the predator.

The scene where the killer, played by the terrific Peter Lorre, is methodically hunted down through an office building, is a master class in suspense and the triple point of view structure (cops, criminals and killer) remains innovative.

Henri-Georges Clouzot, The Wages of Fear (1953)

In a distant South American oil town, four men desperate for a paycheck agree to drive two trucks loaded with nitroglycerin, needed to extinguish an oil well fire, across rickety bridges and bumpy roads knowing one wrong turn could end in a quick and awful death.

Sure, a truck full of nitroglycerin is an excellent way to up the stakes, but the film is also a great example of why backstory and setting up characters is necessary to tell a suspenseful tale. Be patient; you’ll be richly rewarded.

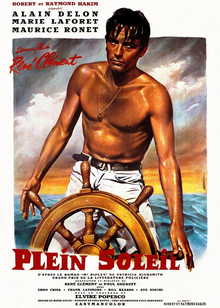

René Clément, Purple Noon (1960)

There are criminals, and then there is Alain Delon playing an impossibly gorgeous Tom Ripley, he of the Highsmith novels. Delon oozes charisma, danger and hunger as he gazes with rapturous desire at all the expensive trinkets wealthy playboy Philippe Greenleaf owns and decides to keep them for himself, along with his girlfriend and his very identity.

There is no question Tom is a bad egg from the start—Delon never telegraphs anything but greed and desire—but the fun is in seeing if he’ll get away with it.

Brian de Palma, Blow Out (1981)

A sound technician recording effects for a cheap horror movie accidentally records a real crime and is roped into a conspiracy. This is a delight to watch for any sound afficionado, and it also has a terrifying villain who is intent on covering up the whole incident, even if it means engaging in multiple, ghastly murders.

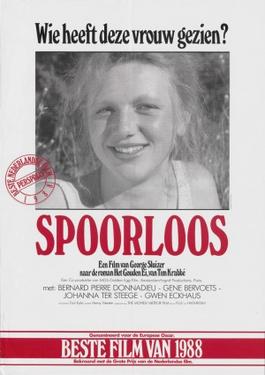

George Sluizer, The Vanishing (1988)

Be careful to watch the Dutch film, not the botched American remake. Titled “Spoorloos,” literally “Without a Trace” in its original release, this is the story of a man on a desperate hunt to find out what happened to his girlfriend who went missing while on vacation.

We know from the beginning who abducted her and why, but you’ll still be at the edge of your seat as this cleverly structured film lures you into a tale of obsession.

***