When I was in college, my roommate lent me a book, A Wild Sheep Chase, by Haruki Murakami. He knew I loved noir and thought I’d also love this postmodern Japanese mystery. I did not. In fact, I threw the book across the room (Sorry, Raj). Yes, it started out in a very hardboiled style with a scarred narrator searching for a missing person, er, sheep (or maybe both). Weird, wonderful. But by the end, the mystery wasn’t really solved, not in any satisfactory way. Sure, I knew more about the sheep and the missing friend, but I also knew less. I felt tricked. I had expected something different, perhaps some feeling of mastery or order that we get when most mysteries are resolved. I picked up the book and read it again, angry. I have read it many times since. I was tricked! I love that trick.

Since then, I’ve come to seek out books that I call Unresolved Mysteries, stories that borrow from the detective genres, then go a little crazy without ever tying things up in neat bows. My novel The Fact Checker follows a magazine-nitpicker-turned-hapless-detective through a series of misadventures concerning secret eating clubs, anarchist parties, and cultish farms. It owes a lot to these off-kilter detective stories. It even has a mysterious sheep (Thanks, Haruki). Perhaps I like these books because, in life, mysteries don’t begin and end with who-done-it. Everything worthwhile is a mystery, and nothing is ever resolved.

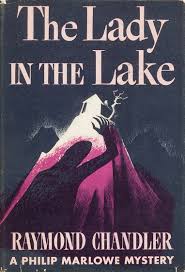

Books don’t have to be “postmodern” to remind us of this. Noir has always been pointing to the strange unknowables lurking in the everyday. Raymond Chandler, for one, filled his novels with as many descriptions of furniture and buildings as he did of clues. Are they clues? (Yes!) I often think of a moment in The Lady in the Lake. Philip Marlowe is watching the house of a doctor who happens to live across the street from a suspect. The doctor is not yet a suspect himself, but Marlowe can’t help but watch his every move: “He was on the telephone now, not talking, holding it to his ear, smoking and waiting. Then he leaned forward as you do when the voice comes back, listened, hung up and wrote something on a pad in front of him. Then a heavy book with yellow sides appeared on his desk and he opened it just about in the middle. While he was doing this he gave one quick look out of the window, straight at the Chrysler.” Marlowe thinks there is something suspicious about him, but what?

Suddenly he switches tone: “Doctors make many phone calls, talk to many people. Doctors look out of their front windows, doctors frown, doctors show nervousness, doctors have things on their mind and show the strain. Doctors are just people, born to sorrow, fighting the long grim fight like the rest of us.” It’s a strange moment: Chandler’s plot-driven surveillance swerves into metaphysical empathy. Then he moves back: “But there was something about the way this one behaved that intrigued me. I looked at my watch, decided it was time to get something to eat, lit another cigarette and didn’t move.” Is surveillance just a form of being nosy? In other words, is it like reading a detective story? Finally, is the real mystery: What are other people?

I’ve put together a list of Unresolved Mystery books that ask that question in different ways. What are other people?

A Wild Sheep Chase by Haruki Murakami

A divorced advertising copywriter and his girlfriend with magical ears set off to Hokkaido in search of a missing sheep and the narrator’s Bohemian best friend. Stuff blows up.

Atmospheric Disturbances by Rivka Galchen

A psychiatrist believes that his wife has been replaced by an exact replica whom he calls the simulacrum. He also indulges in a meteorological conspiracy theory related to the Doppler effect which sends him on a quixotic quest to Argentina while his wife searches for him. It’s a brilliantly funny, tender, and strange portrait of knowing and unknowing, of intimacy and its limits.

Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me by Javier Marías

I don’t think it’s much of a spoiler to reveal the premise of this book which is laid out in the first chapter, but if you don’t want to know it, stop reading here and start the book. The beginning is amazing! The narrator is on a date at the apartment of a married woman – her young son is sleeping in the next room – when she dies in his arms. The rest of the novel is an obsessive surveillance of the dead woman’s family. If you have not read Marías, whose sentences unfold in erudite stream-of-consciousness, qualifying, defining, redefining, and circling back on themselves, this is a good place to start. It’s like a really suspicious Proust stuck inside a thriller.

Riverman by Ben McGrath

In the only nonfiction book on this list, McGrath befriends a vagabond canoeist on the Hudson River. When authorities find his canoe overturned (but no body) in North Carolina, McGrath investigates. He traces the life and wanderings of Dick Conant, a charismatic eccentric, and all the people he met on his watery way. While we never really solve the riddle of Conant, we get a portrait, alternately heartening and disturbing, of America and its castoffs.

Memento Mori by Muriel Spark

“Remember you must die.” This is the message that a mysterious voice delivers to a variety of old people in Spark’s crazy 1959 novel. An inspector is on the case, but for what? The message is true! But, as the inspector says toward the end “If you look for one thing… you frequently find another.” Here we find sociological insight, a comedy of manners, and death. Death is everywhere.

A Separation by Katie Kitamura

After the narrator’s estranged husband disappears, she travels to a Greek island to track him down, or, rather, to wait for him. She doesn’t do much tracking. Instead, the narrator muses, in cool, cutting tones, on the forest fires and class resentment around her and her missing man. She feels the chasm between them: “between two people there will always be room for surprises and misapprehensions, things that cannot be explained.” In the end, nothing is fully explained. “All deaths,” the narrator tells us, “are unresolved.”

The Lady in the Lake by Raymond Chandler

This one is a totally resolved mystery. Marlowe gets his man, or actually that man is randomly shot by the military, we think. Meanwhile, the women who keep masquerading as other women are all sorted out. One corpse is revealed to be another corpse while a second corpse is the first corpse. Wait. What?

***