Speculative fiction. It’s a big umbrella term, and many an author gets embroiled in online (or in-person, in the case of friends Margaret Atwood and Ursula K. Le Guin) skirmishes, debates, and lively banter about what it really means. Personally, I don’t think there’s a right or wrong answer; it’s what it means to you as a writer or reader.

As a kid, I grew up with a dad who took me to Dairy Queens alongside graveyards so he could tell me ghost stories; bought tickets to Alien as I watched, enthralled, and my Swedish cousin ran to the bathroom and puked; encouraged me to consider all things supernatural and extraterrestrial—in other words, the best-worst dad ever.

Parenting skills (or lack thereof) aside, those wild, terrifying, exhilarating experiences imprinted themselves in my DNA as a human and an author. I’m drawn to stories that feature what-ifs, tales that dance within the realm of reality only to dip into the murk of what could be possible…if.

Speculative—to me—rubs up against horror, makes a social commentary, frequently includes some form of time travel, and very often features technology, government or corporations run amok with power and Borg-ing up the tattered remains of our humanity.

In my debut novel, The Found Object Society, my protagonist, Greta Davenport, is a train wreck of a socialite who has harbored guilt over the death of her parents for twenty years. She’s filled that abyss of grief with drugs, booze and sex until one night—when she nearly crashes her car while driving drunk—she receives a mysterious blank white card that slides under her front door. Within it, she discovers a hidden QR code, an invitation to join (for a mere $500,000) the Found Object Society, a secretive society hidden in the bowels beneath one of NYC’s oldest buildings, 273 Water Street, in the South Street Seaport. The society allows members to select one of thousands of objects from different eras and regions and travel back in time to experience the death of the last person who died touching it… and live to tell the tale.

It’s a trippy, fun ride that allowed me to bake in some of my favorite fiction goodies: organic time travel without complex machinery; otherworldly operators of a society with potentially nefarious intentions; writing in different POVs; a lot of creative ways of dying, all while addressing addiction, the excesses of the uber wealthy, and the steely thread of grief that weaves through our lives at one point or another.

Below are some of my recent (and one of my oldest) speculative favorites that thrillingly delve into crime and murder in its many forms.

A Step Past Darkness, Vera Kurian

Kurian’s second novel is a delicious ode to Stephen King’s It, featuring multiple POVs and timelines along with a smattering of the supernatural, thanks to a very scary priest. Six classmates witness a horrifying crime in their idyllic town’s abandoned coal mine and take a vow of silence, never to see one another or speak of it again. Cut to twenty years later, and the murder of one of their own brings them back. The combination of the town’s cult-leader (or worse) coupled with eerie depictions of the neighboring town—abandoned because of a decades-long smoldering coal mine fire—makes for a nuanced and creepy read.

The Paradox Hotel, Rob Hart

Time travel for the ultrarich? Check. Powerful government entities privatizing the technology for their dubious gain? Check. One grieving female security officer trying to solve a murder while she slips between the present and past due to her time travel sickness called, Unstuck? Check and check. The time portal is starting to glitch; baby dinosaurs keep popping up; and things are going all kinds of wrong at the Paradox Hotel. Here, Hart showcases his mastery of melding noir, sci-fi and thriller in this wild ride.

The Dream Hotel, Laila Lalami

A Moroccan-American scientist is detained at LAX because an algorithm has predicted that she will commit a violent crime against her husband based on information found in her dreams. How many of us would get locked up, institutionalized, if our dreams were interpreted at face value? The thought of it alone is hive-inducing and a terrifying violation of privacy—feeling eerily close to our current trajectory. As the protagonist’s detention drags on, the tension builds to such a point I almost needed an antacid (in the best way possible).

Good Neighbors, Sarah Langan

No one skewers the sweet candy-coating of suburbia and lets spill the gooey gore inside better than Langan. Set in the very near (and increasingly hot) future, an unconventional family has moved to picture-perfect Maple Street, sending ripples of disapproval throughout the well-manicured McMansions. Soon after, a giant sinkhole opens up in the park, swallowing the daughter of the neighborhood’s self-appointed Queen Bee. Rumors and accusations fly, directed squarely at the outcast new family. Laced with ruthless humor and tension, this novel lays bare the noxious underbelly of the American Dream.

Time and Again, Jack Finney

First published in 1970, this book has set up shop in my heart and mind since I first read it 30 years ago. An advertising artist is asked to assist in a hush-hush government operation exploring the possibility of time travel. Eager for the opportunity, he goes back to 1882 New York City, not only for his employers but also trying to solve the mystery of a half-burnt letter from the same year that hints at a terrible death and a fire. What he doesn’t count on is falling in love with a woman in 1882 and bringing her back to the present. This is the book that got me hooked on the idea of time travel being a cerebral thing instead of a complex machine—requiring no more than taking a seat and gazing out the window onto Central Park from an apartment in the iconic Dakota building.

Siren Queen, Nghi Vo

Vo takes the glamour of 1930s Hollywood and pulls back the curtain to reveal the terrifying monster lurking behind. A young Chinese-American girl, Luli, is determined to become a movie star and break free from a life working at her parent’s laundromat. She worms her way into the studio system—signing a contract with the appropriately-named exec, Oberlin Wolfe—and refuses to take the stereotypical roles usually assigned to Asian girls. Through Luli’s eyes we see the hellscape of the studio lot, where monsters roam, dark magic is in play, and (literal) sacrifices must be made to gain silver screen immortality… but is our narrator reliable? Dizzying and frightening, Siren Queen left me delightfully off-kilter.

The Puzzle Box, Danielle Trussoni

The second installment of a two-book series, The Puzzle Box completely works as a standalone. Mike Brink suffered a traumatic head injury as a teen and now has savant syndrome, which has given him remarkable puzzle-solving abilities. In this story, the Emperor of Japan has hired him to decipher the Dragon Box, a deadly puzzle box that has remained unsolved since the 1800s and left many a dead body in its wake. It’s believed that inside the box is a long-held secret that could upend the fate of the Japanese empire. There’s also a very nasty tech giant who died in the first book but whose consciousness lives (dare I say, thrives?) in the ethernet and is desperate to get ahold of Dragon Box’s secrets. There’s good reason this pulse-pounding ride won the LA Times Book Prize for Mystery/Thriller.

Jackal, Erin Adams

Here’s a case in which speculative and horror intertwine, holding a mirror to racism. A Black woman reluctantly returns to her predominantly white hometown for her best friend’s wedding. On the night of the event, the bride’s daughter (a young Black girl) disappears into the woods—the same woods where young girls (all of them Black) have gone missing for years and met with grisly fates. The police investigation into this and other disappearances has been apathetic, at best. Something evil lurks in the forest. Is it human or supernatural? The protagonist’s hunt for the truth brings her to the edge of sanity, and uncovers a horrific pattern that stretches back to 1889 and a tragic dam collapse. Beautifully rendered, this story hit me hard.

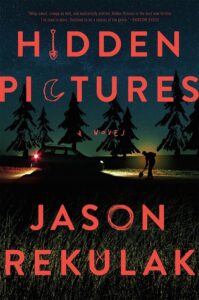

Hidden Pictures, Jason Rekulak

One million copies sold, wow. This novel leans heavily into horror and features a child’s illustrations throughout, which add so much to the creepiness of its premise: A young woman who is a recovering addict becomes a nanny for an idyllic-seeming family. The young boy under her care is drawing increasingly disturbing pictures that seem to point to the truth behind a murder on the property many years earlier. Seeing the childlike scrawl of these pictures smattered throughout the book lends an unusual and genius approach to the storytelling—visual plus verbal. The story speaks with power to the perceived societal biases of addiction and recovery. Several beautiful special editions of Hidden Pictures are also available that amp up the illustrations and, no surprise here, Netflix has also optioned the novel.

***