“My name is Carson Drew and this is my assistant, Nancy.”

With that deep cut—or maybe it wasn’t all that deep—in a February 2007 episode, the makers of the TV series “Veronica Mars” put an exclamation point on their obvious love of mystery novels for young people. It’s not like we didn’t know that high-school sleuth Veronica was inspired by classic “juvenile” mysteries, but when Keith Mars assumed Nancy Drew’s father’s name for an undercover mission, it felt incredibly right.

And it was testimony to the staying power of mystery solver Nancy Drew—the star of a current TV series—and her compatriots Joe and Frank Hardy, Jupiter Jones of the “Three Investigators” books, Turtle Wexler of “The Westing Game,” Leroy “Encyclopedia” Brown and Enola Holmes, the smarter, younger sister of Sherlock and Mycroft.

With Enola making her movie debut on Netflix on September 23, featuring Millie Bobbie Brown as Enola and Henry Cavill as Sherlock in an adaptation of Nancy Springer’s books, it seemed like a good time to look at some of those juvenile novels and series that served as an entry point for young readers of mysteries.

This article won’t be exhaustive by any means; there are simply too many good-to-great mysteries for young readers out in the world, thank goodness. But here are a few.

The Boys from Bayport

Before Edward Stratemeyer and his self-named publishing company, the Stratemeyer Syndicate, introduced the Hardy Boys in 1927, there were plenty of print adventures for young boys and girls. A newspaper advertisement in the June 29, 1927 edition of the York (Pennsylvania) Dispatch listed a few. Besides the Hardy Boys and Tom Swift, most of the series listed in the advertisement are mostly forgotten now, except to aficionados: Don Sturdy, the X-Bar-X Boys, Garry Grayson, Tom Slade, Pee-Wee Harris, the Radio Boys, the Rover Boys and Jerry Todd.

(For girls, the ad offered the adventures of the Bobbsey Twins, Polly Brewster and the Girl Scouts. Our heroine Nancy Drew would not come along for a couple of years, as we’ll see.)

The juvenile mystery book as we know it—a point of entry for generations of readers who would grow up to relish as diverse a selection of investigators and troubleshooters as Jack Reacher and Irene Kelly and Tess Monaghan and Easy Rawlins—was about to be born.

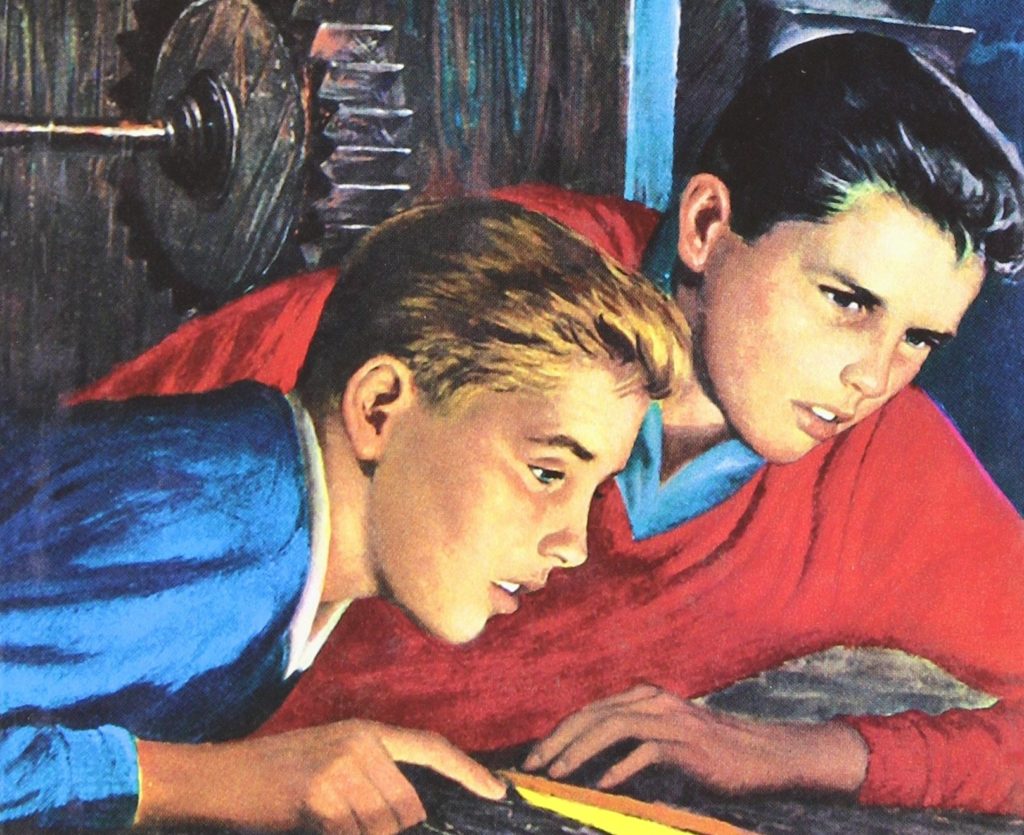

For their 75 cents—50 cents in Salt Lake City, the Deseret News told us—young book buyers got “The Tower Treasure,” a thrilling adventure published under the Stratemeyer Syndicate pen name Franklin W. Dixon. Brothers Frank (16 years old in the earliest books) and Joe (15) Hardy lived in Bayport, a fictional burg within driving distance of New York City that had more smugglers, spies, saboteurs, thieves and mysterious and exotic strangers per capita than any city in the world.

Although Frank and Joe were still in school, the brothers and friends Chet Morton, Tony Prito and a few others regularly investigated thefts, disappearances and other mayhem. Sometimes they assisted their private detective father, Fenton Hardy, on tough cases. Their daring-do got a few “tsk-tsks” and worried looks from their mother, Laura—a character I barely remember from reading the books—and their Aunt Gertrude.

Like boys throughout the years, I devoured the books. The library at my small rural elementary school—how small? My glass had 50-some students—remained open during the summer so we could check out books. I took home eight Hardy Boys books every week, the limit of books we could check out. (My 1960s grade-school reading list also included horse stories, books about mythology and celebrity autobiographies like Sammy Davis Jr.’s “Yes I Can!” My tastes were diverse.)

Over the decades, some school librarians apparently disapproved of juvenile books. But I was lucky that my school’s librarian recognized that all reading is good reading and that it only leads to more reading. (Thank you, Mrs. Jeffers.)

Not enough can be said, by the way, about the importance of school libraries to young readers. Libraries of every kind, as well as the Scholastic Book Fair, opened magical doorways for us, just as great teachers did and still do.

If you’ve read the Hardy Boys books, you know the Hardy Boys books. They’re highly formulaic and almost every one features Frank and Joe, usually working on behalf of someone but sometimes just butting into a mysterious situation because they love intrigue, tooling around Bayport on their motorcycles or in their convertible, following shady-looking characters or getting captured and tied up by shady-looking characters.

Frank was a “thinker” while Joe was “impulsive,” but each boy was really a surrogate for the boys and teenagers who read the books. They could be ciphers personality-wise and still solve ciphers, clue-wise.

The formula was and is comfort food, of course, and the Stratemeyer Syndicate turned out stories like Swanson turned out frozen TV dinners: Edward Stratemeyer—and later his heirs—produced outlines and story and character notes for writers, including the original Franklin W. Dixon, Leslie McFarlane. “Dixon” fleshed out the skeletons. Publisher Grosset & Dunlap—and later Simon & Schuster—released the books in regular fashion, publishing three their debut year of 1927.

In 2001, The New York Times reported—on the eve of the series’ 75th anniversary—that the Hardy Boys books still sold more than a million copies annually. The Times correctly noted that Edward Stratemeyer’s mass-production skills made him “the Henry Ford of children’s fiction.”

The books’ ghostwriters reportedly were paid as much as $125 and as little as $75 for each adventure, a good sum at the time. Still, Stratemeyer and Grosset & Dunlap were making money hand over fist. Melanie Rehak’s 2006 book, “Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her,” reported that more than 115,000 of the company’s series books were sold by 1929.

How many Hardy Boys books have been published? Well, it depends on if you take into account works other than the core “Hardy Boys Mystery Stories.” Mark Connelly’s 2008 book, “The Hardy Boys Mysteries 1927 to 1979: A Cultural and Literary History,” says that 190 volumes were published from 1927 to 2005, although Connelly notes that only the first 58 are considered canon by some fans. Another couple of hundred differently titled books in later, more updated series has been published.

And then there are the curiosities like “The Hardy Boys’ Detective Handbook,” a 1959 volume credited to Dixon “in consultation with Captain D.A. Spina,” the latter of the Newark, New Jersey Police Department. In the book—a copy of which rests on my bookshelf—chapters can be found devoted to “Fingerprint Clues,” “Surveillance,” “The Value of Shoe Prints, Tire Marks and Tool Marks: Plaster Casts and Moulage” and “Criminal Slang and Legal Terminology.”

In the latter chapter, we learn that “bad news” is criminal slang for the check at a restaurant, the “big house” means penitentiary and “beak” means nose. I can’t tell you the number of times I benefitted from knowing that “caught with a biscuit” meant “found with incriminating evidence.”

Among the most important rules of surveillance? “Act nonchalant.”

A lot of the success of the Hardy Books books depended on newspaper advertising, libraries and word of mouth, because a search of newspapers online found very few news articles mentioning the books in the series’ first few years. For all the influence they would have on generations of readers, the books were disrespected by some adults and institutions. The Times story from 2001 noted that the chief librarian of the Boy Scouts of America even produced a pamphlet about the books and other, similar series. Its title? “Blowing Out the Boys’ Brains.”

In 1959, the Stratemeyer Syndicate undertook the task of revising the Hardy Boys books—as well as the companion Nancy Drew series—to eliminate dated references to roadsters and the like and, oh yeah, horrifying racial characterizations. As hugely popular as the first three decades of the books were, it’s possible the revised versions were even more accessible to young readers, as late-era Baby Boomers and the children of Baby Boomers discovered the old stories.

Decades later, revisions continued and all-new adventures were written. But it was the original and unexpurgated stories and their revised versions, however, that kept the teen sleuths of Bayport in the hearts and minds of young readers. So much so that in the late 1920s, Stratemeyer recognized the need for a female counterpart.

The Mystery Queen of River Heights

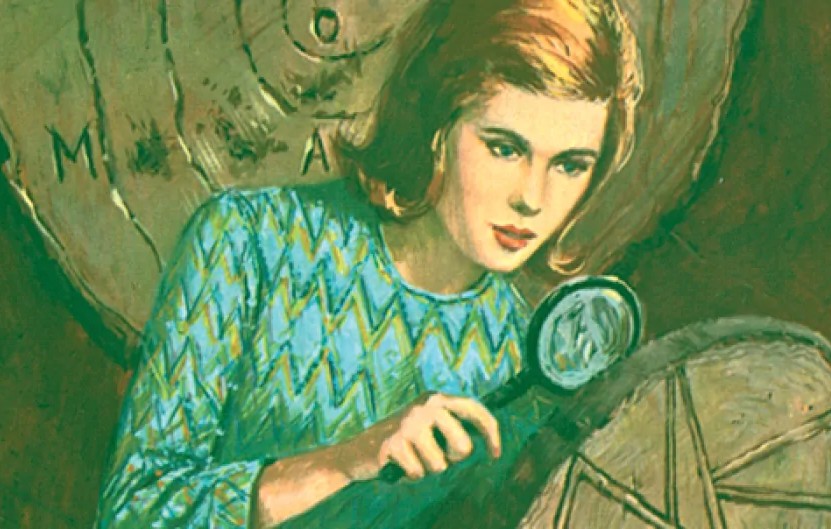

We can go ahead and say it: Nancy Drew, extraordinary young woman and ace detective, could have been insufferable.

“Nancy Drew, an attractive girl of eighteen, was driving home along a country road in her new, dark-blue convertible,” begins the “The Secret of the Old Clock,” the first of the Nancy Drew Mystery Stories. (At least thus begins the revised version from 1959.)

“’It was sweet of Dad to give me this car for my birthday,’ she thought. ‘And it’s fun to help him in his work.’”

“Her father, Carson Drew, a well-known lawyer in their home town of River Heights, frequently discussed puzzling aspects of cases with his blond, blue-eyed daughter.”

“Smiling, Nancy said to herself, ‘Dad depends on my intuition.’”

Okay, so if you didn’t hate-read Nancy Drew’s 175 volumes of adventures—starting with the 1930 publication of “The Secret of the Old Clock” and ending in 2003—you probably admired her. If you were a girl you wanted to be just like her—pretty, well-to-do, smart, popular—and if you were a boy … well, you were probably reading the Hardy Boys.

There’s a lot to like about Nancy Drew. Not the least of those things is that she undoubtedly inspired more girls to read. She also probably inspired girls to take charge of their lives and not worry about whether some Ned Nickerson type liked her or not.

Nancy’s 1959 makeover courtesy of the Stratemeyer Syndicate made her 18 instead of 16 and, as “The Mysterious Case of Nancy Drew & The Hardy Boys,” Carole Kismaric and Marvin Heiferman’s essential 1998 overview of the books, notes, tamped down some of her wilder tendencies, like driving too fast.

Nevertheless, as the authors note, “As intelligent as Nancy is, she sometimes becomes so obsessed with her mission that her judgment clouds over and she gets reckless. She’ll ignore warnings, chase red herrings and take senseless risks. Time after time, she brushes off the concerns of friends, experts and sensible adults.”

Luckily, Nancy has a cadre of friends who help her out—or at least keep her company—on those missions. Her best gal friends, Bess Marvin and George Fayne, are there to keep her company on stakeouts and share picnic lunches. Between the two of them, Bess and George are probably more like the girls who grew up reading the books. Bess is the more traditionally girly, worried about her looks, while George is the tomboy with a short hairdo. George’s portrayal inspires interpretations of her sexual orientation. A 2017 article in The Mary Sue suggested that a planned reboot needed to outright declare George as lesbian.

The strength of Nancy Drew is that readers feel passionately about the books—more so than most Hardy Boys readers feel about those books—and see themselves in the characters.

That helps explain why Nancy and her friends remain pop culture icons. “Nancy Drew,” a series starring Kennedy McMann, debuted on the CW network in October 2019 and aimed to update the classic character with edgier storylines and situations. A second season has been ordered by the network.

The current “Nancy Drew” TV series isn’t the first time the girl sleuth or her Hardy Boys counterpoints have been brought to life, of course. The live-action adventures of the three might have reached their peak in two seasons of an ABC series that began in 1977, featuring Parker Stevenson and Shaun Cassidy as Frank and Joe and Pamela Sue Martin (and later Janet Louise Johnson) as Nancy. Martin broke out of her role with a pictorial in Playboy magazine in 1978.

If not for the nudity and objectification, it would have been a norm-breaking move right out of Nancy’s playbook.

The Movie Director and the Young Gumshoes

It’s hard to imagine, looking back from the perspective of 2020, just how big a cultural touchstone film director Alfred Hitchcock was, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s. Hitchcock, frequently cited as the master of suspense cinema, was the true star of each of his movies, including “Psycho” and “North by Northwest,” by virtue of having become known as the maker of twisting-and-turning, shocking thrillers. He narrated many of the coming attraction trailers for his films and could be glimpsed in cameos in the movies themselves.

But Hitchcock was literally a personality on TV, where he hosted a weekly anthology thriller series, “Alfred Hitchcock Presents,” from 1955 to 1965. He appeared on camera to introduce each story in a short monologue featuring macabre and punny jokes. He became a household name unlike any other film director would until Steven Spielberg.

So it makes a kind of sense that, beginning in 1964, Random House published a series with the umbrella title of “Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators.” The series was created by Robert Arthur Jr. and several of the earliest of the 43 books published through 1987 were written by him.

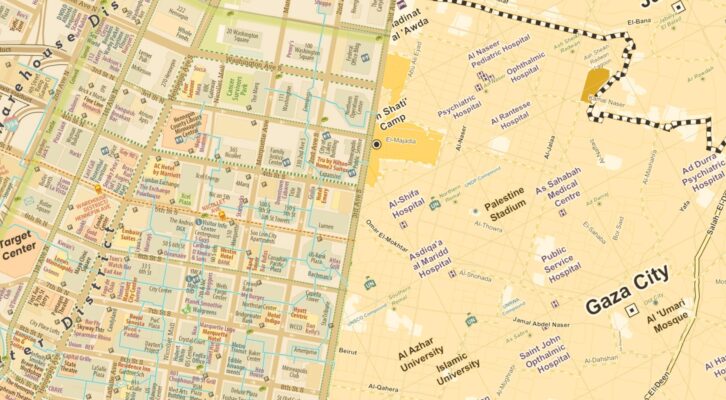

In the books, Hitchcock engages in a battle of mystery-solving wits with a trio of underage private eyes from Rocky Beach, a town not far from Los Angeles. It is a town that, like Bayport and River Heights, has more than its share of wrongdoers.

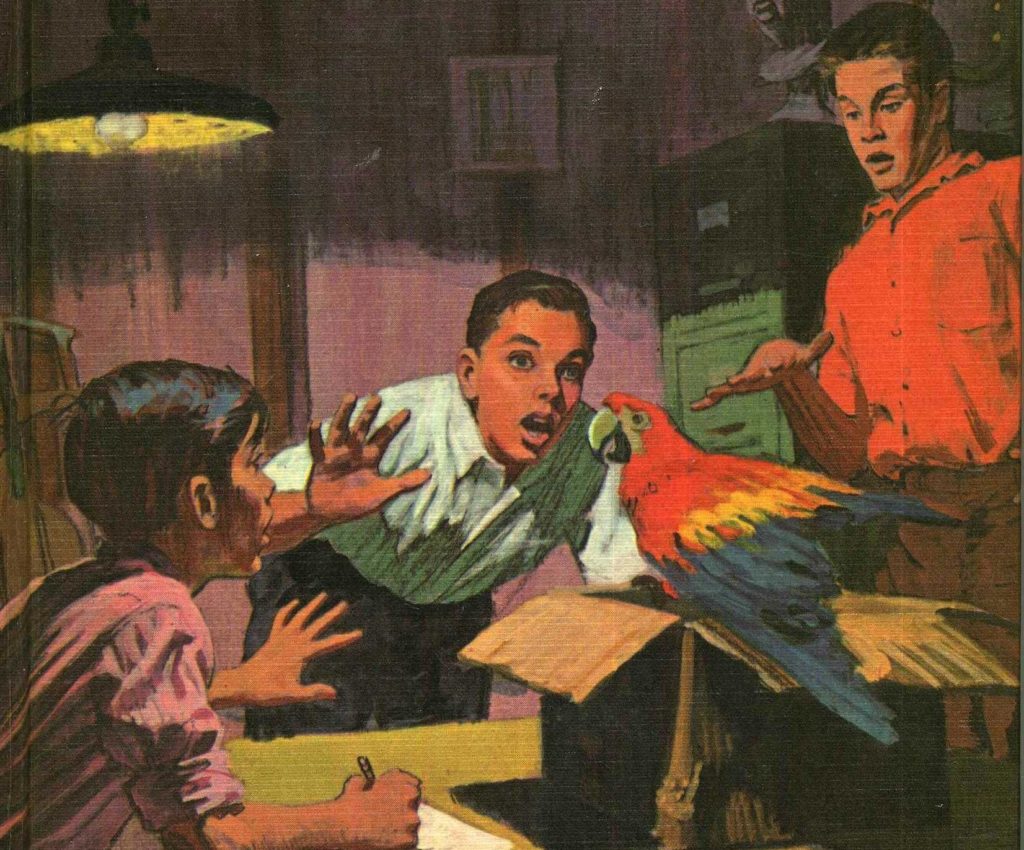

The Three Investigators who shared top billing with Hitchcock were Jupiter Jones, Pete Crenshaw and Bob Andrews. Like trifurcated versions of the Hardy brothers and Nancy, the three brought deductive reasoning, observational skills, daring and technical know-how to mysteries that would often start simple—such as who took value-less paintings created by a little-known artist in “The Mystery of the Shrinking House”—and escalate into kidnappings, encounters with threatening thugs and bicycle chases—the latter because none of the Three Investigators was old enough to drive.

Jupiter Jones was first among the Three Investigators—literally; the investigators would call each other “First” and “Second” and, in the case of unfortunate Bob Andrews, the decidedly un-snappy “Records.”

After Hitchcock’s agreement to let his “character” be used expired, he was replaced as the boys’ mentor by Hector Sebastian and Hitchcock’s name was dropped from the series’ umbrella title.

(While the Three Investigators books were being published in the 1960s, another young detective, Leroy Brown, began appearing in a 29-book series. Name doesn’t ring a bill? How about Encyclopedia Brown? Donald Sobol created Encyclopedia—that’s not awkward to say at all—as a way of presenting puzzles to his readers. It was an approach that was later perfected in “The Westing Game,” as we’ll see.)

In much of the world, the Three Investigators aren’t the household names that Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys are. But in Germany, the books have not only continued as popular reads but continued as new product, with 200 books, two movies, audio dramas and a live stage show – featuring the actors from the audio dramas—touring the country.

Jupiter Jones lives!

Get a Clue—and a Newberry Medal

Not every juvenile mystery is hugely popular and acclaimed, but Ellen Raskin’s 1978 novel “The Westing Game” won the prestigious Newberry Medal as a “distinguished contribution” to American literature for children.

It’s easy to see why. While “The Westing Game” is a mystery novel for young people, it is so well written and clever that it transcends any stereotyping of the genre.

The book, which is something of a read-along puzzle, follows the adventures of a group of people who live in Sunset Towers, a brand-new apartment building on the Lake Michigan shore.

The new tenants of the apartments—most of them adults—are recruited to play a game by representatives of the late developer of the building, businessman Sam Westing. The 16 players are divided into eight teams of two and are told that they are heirs to Westing’s fortune of $200 million—but only if they solve the elaborate word-play puzzles Westing has left behind in his will.

“The Westing Game” wouldn’t be a mystery without not only the puzzles but also twists and turns. Some of the players have hidden secrets and much of the premise is upended.

Raskin’s book is a clever spin on a “And Then There Were None”-style mystery, with several suspicious types and several admirable competitors … or are they?

Easily the most likable character—and most relatable for young readers—is Tabitha Ruth Wexler, known as Turtle. She’s a super-smart 13-year-old who has something of a reputation for kicking people in the shins. But not even Turtle is a simple, straightforward character. Raskin shows her respect for the intelligence of her readers by making Turtle a more multi-faceted character than many young people in books for young people.

“The Westing Game,” like some other entry-point mysteries, has found life outside the printed page. “Get a Clue,” a TV movie adaptation, was produced in 1997, and Variety reported in September 2020 that a series version of the book was in early development for HBO Max.

Holmes Sister Doin’ it for Herself

Really, the idea of young women solving mysteries is about as old as juvenile fiction itself. Nancy Drew paved the way for young women like the four friends who debuted in 1932’s “The Merriweather Girls and the Mystery of the Queen’s Fan” and appeared in four books in a short period of time.

It’s hard to imagine a better modern-day realization of the idea of a smart young woman solving mysteries than the Enola Holmes Mysteries.

Nancy Spring created the Enola Holmes Mysteries series in 2006 with an audacious conceit: Take the family tree of the best-known detective of all time and give it a shake, prompting a new, younger, smarter, better detective to fall out.

In “Enola Holmes and the Missing Marquess” and five subsequent books, Springer creates an intensely likable protagonist truly born before her time. Enola is the 14-year-old sister of Sherlock and Mycroft Holmes. Sherlock is already a well-established consulting detective in London and Mycroft is far along the path to his shadowy life in government service by this point.

On Enola’s birthday, her mother disappears. Sherlock and Mycroft believe their mother decided to drop out of society, but Enola—because she’s been raised by the mother of geniuses—suspects differently.

Before her brothers can send her to a boarding school to “refine” her into a British gentlewoman, Enola eludes the boys and sets out on her own, intent on determining the truth behind what happened to her mother. In the process, she helps other people, solving their mysteries while maintaining her own undercover life, avoiding her brothers and disdaining the rigid role that 19th-century British society forced women into.

Enola becomes a private detective while operating in a world that resists mightily the idea of an intelligent, freethinking young woman.

The series seemed like a natural for the screen, and the trailer for the movie, starring Millie Bobby Brown, the “Stranger Things” star, Sam Claflin as Mycroft, Helena Bonham Carter as Eudora Holmes and Henry Cavill as perhaps the hunkiest Sherlock ever, make it look like a lot of fun.

And, like movie and TV adaptations of young sleuths before, the “Enola Holmes” movie just might inspire young people to go to the written word source. Which is a good thing.