Among the reasons to love Charles Vincent Emerson Starrett (of which there are multitudes) is that, notwithstanding his status as a passionate bibliophile, critic, poet, essayist, novelist, and bon vivant, the man never graduated high school. This always rang a bell with me.

I may have my bachelors in theatre and literature, but I can claim no graduate experience whatsoever. (I’ve been roundly booted from academic journals when this scholarly deficiency was discovered and asked politely whether I wouldn’t like to write the introduction instead; I’m swell at those.) To boot, I’ve never taken a creative writing class in my life, and have always looked at elite programs in which venerable literary gods break the egos of their students until Pulitzer material gushes from the pinata with a kind of fascinated queasiness. I don’t know whether Starrett would have remotely liked me, but I know for a fact I’d have taken a mighty shine to Starrett. Like me, he wrote books because he grew up marinating in them. These might not be lofty beginnings, but they’re highly egalitarian ones.

Vincent Starrett was raised above his father’s Toronto bookstore and he lived in the children’s literature section. I was raised in a paper mill town in Washington State and I lived in the public library’s carpet-lined bathtubs in the children’s literature section. Starrett never lost his unabashed enthusiasm for all things adventurous, mysterious, piratical, alien, thrilling, or fantastical. He likewise never misplaced his affection for soothing comforts: The Boxcar Children, Treasure Island, Little Lord Fauntleroy.

His tastes were never sullied by pseudo-intellectual elitism, and if he were alive today, I’d bet a Benjamin Franklin that he would own first editions of The Hunger Games series, but possibly not Infinite Jest. There’s nothing wrong with enjoying David Foster Wallace, mind—I’d just lay my money on Suzanne Collins as a sure thing.

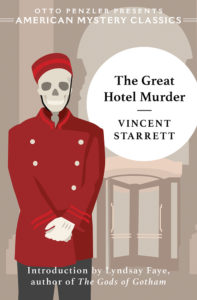

Malcolm Gladwell in his now-iconic book regarding extraordinary success, Outliers, makes a lot of hay about being born in the right place at the right time. Starrett was undoubtedly born in the right locale—he had hundreds of fictional worlds at his fingertips the instant he descended a staircase. But in a way, the timing of his birth was likewise fortuitous. 1934, the year Recipe for Murder was published in Redbook Magazine (later to spread its wings and expand into The Great Hotel Murder when published the next year by Doubleday’s imprint, the Crime Club), was a darkly troubled one.

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt arrived in office in 1932, a quarter of America’s wage earners were unemployed. Nine thousand banks had closed by the next year, between them magically disappearing two-and-a-half billion dollars’ worth of deposits. It’s hardly surprising, therefore, that by far the most popular entertainment was unrepentantly escapist: radio serials, screwball comedies, sports rivalries, sci-fi fantasias. Whodunits slotted nicely into this groove and, thankfully, Starrett of all people knew his way around mystery novels.

He’d been writing his PI sleuth Jimmie Lavender in short story format for around two decades by the mid-thirties, racking up fifty or so published cases, and had started experimenting with novels helmed by Walter Ghost in 1929. His utterly and endlessly beloved essay collection The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes was released in October of 1933. He had experience as a reporter for the Chicago Tribune, then as their book critic, and by the time he sat down to write what would become The Great Hotel Murder, let’s just say there was a pretty solid built-in audience queuing up for this sort of material. Clearly it was high time for Starrett to write his own avatar as a gentleman detective.

Don’t imagine that I say this in any pejorative fashion. On the contrary. That would be hypocritical, as the vast majority of the major characters in my novels possess various striking similarities to yours truly. And I’m not saying definitively that Riley Blackwood, the theatre-critic-cum-amateur-sleuth who stars in The Great Hotel Murder, was intended to be just a smidge autobiographical. It may well have an accident. Certainly, Blackwood positively glows with appreciation for his Chicago habitat. “Out on the lake an excursion steamer was plodding into port, outlined in colored lights against the purple sky. The endless line of motorcars was coughing past, as always, in the street below. All the world was wagging merrily,” he gushes after recovering from a conk on the head, “appalled by his own isolation.”

Starrett was equally in love with his chosen Windy City, from its powerhouse publishing industry to its wild atmosphere to naming Jimmie Lavender after a pitcher for the Chicago Cubs. Indeed, by the time Blackwood finds himself in the Wisconsin woods attempting to locate a key suspect gone missing, his preference for Chicago grows downright humorous.

“He was ardently sick of trees, in spite of an early-morning notion that dwellers in the city were oafs and half-wits. Trees hemmed one in. They weighed mysteriously on the senses. He hoped that he would never see another adjectival tree. The poet who could sing of trees was full of bats and mice and fleas. Riley Blackwood, jiggling along a country road in northern Wisconsin, would have given up a dollar and a half for just one glimpse of a sputtering white electric sign in Clark Street.”

But this observation regarding love of one’s metropolis is surely inconclusive—who is Philip Marlowe without Los Angeles or Sherlock Holmes without London? It may also be happenstance that Blackwood, like Starrett, is bony and satirical and bespectacled, with a genial disposition and a penchant for irony. It’s possibly pure chance that both men are newspaper critics, both men started off as journalists, and both men collect mysteries (Blackwood rather more aggresively than Starrett himself, I grant, since to my knowledge Starrett never held any villains at gunpoint). Both men have an eye for the fair sex—Blackwood as a roving bachelor and Starrett both in and out of wedlock on occasion—but what of that? Of Blackwood we further learn, “The number of [his] books was legion… He liked to idle there among them, in certain moods, and feel himself a part of that great company of crime savants who stalked and blustered in so many of their pages.” This passage could equally well describe Starrett, but maybe my own love of detective stories is causing me to hatch ludicrous conspiracy theories.

In any event Riley Blackwood, for some inexplicable reason, is allowed to traipse all over his friend Widdowson’s lavish downtown hotspot, the Hotel Granada, solving crimes. (Or rather, attempting to solve crimes.) Briefly, a man named Dr. Trample has switched rooms with a man named Jordan Chambers (an alias, we later learn), and Chambers the next morning is found tangled in his sheets, quite dead. Who better to consult than an arts critic?

We know the drill here; the police will be flummoxed and the amateur will capture the flag with a flash in his eye and a whistle on his lips. But as I said, in the mid-1930s, when Chicago was booming and the Southern Plains were turning into the Dust Bowl, why not consult an arts critic? Blackwood makes keen observations, draws astute inferences, knows the prettiest actresses, trades barbs handily, and is good at card tricks. All admirable qualities. And qualities that perfectly suit this sort of mystery—we’re not solving the travails of destitute America here, and we’re not avenging a lynching or looking for a missing child. There’s a swank hotel dealing with an apparent suicide that Blackwood insists is a murder, and a lot of varyingly attractive people whirl about through the lobby’s revolving doors.The Great Hotel Murder is fun, and Starrett knew better than to stick his nose in the air when enjoying the book in front of it.

The Great Hotel Murder is fun, and Starrett knew better than to stick his nose in the air when enjoying the book in front of it.And so do I. It would take a tremendous effort and churlishness of spirit not to like The Great Hotel Murder. The varyingly attractive people I mentioned are tropes, yes, but in Starrett’s deft hands, they are much more. Sleazy PI antagonist Gene Cross is thuggish, but he’s also cunning. Our somewhat-heroine Blaine Oliver is beautiful and witty, but she’s refreshingly insightful and short-fused, too. Harry Prentiss, her dashing young friend, toes the line between ally and suspect until the final pages, and the elusive but affable Dr. Trample is either the obvious murderer or else the victim of astonishingly vexing coincidences. Kitty Mock—actress, occasional dope addict, and wife of the dead man—might be a bit empty between the ears, but she’s shockingly practical and such a very talented actress that she can get away with all manner of mischief without a degree in rocket science, thank you very much. Yes, Riley Blackwood is a well-off young intellectual, but he isn’t above diving into the notoriously inhospitable waters of Lake Michigan to save a man overboard.

It must be noted that Starrett would have been well aware of the character types he was toying with; he was too much of a literary critic not to have done it deliberately. And as familiar a name as Starrett’s is to any admirer of the Great Detective, Mr. Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, another legendary Sherlockian contemporary of his ought to be mentioned here, and that is Monsignor Ronald Knox—priest, radio personality, translator, essayist, satirist, lecturer, and fellow shameless peddler of original detective fiction. In 1929, Knox codified the Golden Age of Detective Fiction into a Decalogue of ten hard and fast rules. Starrett follows most of them, and that’s a satisfying and familiar blanket to snuggle inside. The criminal is mentioned early on, for example–no ghosts need apply–we aren’t infested with secret chambers, and twins fail to plague us.

But equally satisfying are the aspects of this rulebook Starrett flirts with breaking or outright ignores. No “Chinaman” (with all apologies for even mentioning this regrettable edict) is meant to figure in the story according to Knox; Starrett, however, who lived for a year and a half in Peking, promptly and with a certain flair announces that Blackwood’s beloved Aunt Julie employs a Chinese servant. I can’t help but think he knew exactly what he was doing. And Father Knox’s Rule Six, that “no accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right,” is altogether run over by a roadster in The Great Hotel Murder. Blackwood knows the exact cut of Dr. Trample’s jib from the beginning; it only remains to understand what the devil is going on.

He’s also helped by a frankly hilarious number of accidents, which only adds to Blackwood’s charm. One gets the feeling (and again, here we veer into territory that may ever so slightly resemble Starrett himself) that Blackwood would absolutely love to be Sherlock Holmes if he could, but is plagued by that pesky ailment so many of us suffer from: being a mere mortal.

Not everyone can be expert in boxing and chemistry, dirt types and dialects, ninja skills and legal arguments. It’s exhausting just to contemplate being Sherlock Holmes for a day, let alone an entire lifetime. That’s not to say the heroes don’t share marvelous similarities. Regarding Gene Cross, Blackwood mentions, in the most casually Sherlockian fashion to his friend Blackwood, “He’s a key piece in this puzzle. He has a very irregular outline, and God knows where he fits.” Like Holmes, Blackwood is well aware we are each starring in our own drama, that life imitates art and art life, and he has a tendency to wax philosophical about it. Also like Holmes, for a character about whom we are being told a story, he is weirdly self-aware of his own existence. Holmes knew about Watson’s Strand Magazine chronicles; many a riposte was aimed at them. As the plot gains momentum, we learn of Blackwood, “He had set out to solve the mystery in his own way; and his own way had been, of course, the way of the cerebral story-book and stage detective.” When he finally does crack the case, a still more meta-fictional inner monologue pours forth.

“And what a simple explanation, if that were all of it! Simple and natural—and surprising. The good old formula. The sort of thing that lay concealed beneath the red-herring trickery of all good fictional problems, then bobbed up at the end to knock the cock-eyed reader cold with astonishment. And with dismay that he had not guessed it earlier.”

“’Elementary, my dear fellow! It has all been obvious from the beginning. It was the butler, of course!’”

Unfortunately for Blackwood (and perhaps for Starrett, too), he isn’t Sherlock Holmes and never will be. Regarding his own foibles and failures, he’s both understandably tetchy yet endearingly philosophical. The Great Hotel Murder isn’t the knot of Euclidean problem-solving that Sherlock Holmes wistfully thought all cases ought to look like; it’s a romp, much more to Watson’s tastes than Holmes’s refined sensibilities. Blackwood finds himself drinking his breakfast, snaking an arm around alluring women, making outright errors in judgment, tripping over his own feet, getting whacked in the noggin, and sneaking around the woods on tippy-toe like an adolescent heading for a forbidden bonfire in a way Holmes would have found downright embarrassing.

Watson would have loved it, however. And so do I. And so did the public. The Great Hotel Murder hadn’t even cooled off from its printing when Fox Films snapped up the movie rights. By 1935, lo and behold, it was already a flick starring Edmond Lowe and Victor McLaglen. Although Starrett liked to quip that the film differed enough from his novel that he was as surprised by the ending as anyone else, he must have been proud to see his efforts reap so much success so quickly, and bring so many people pleasure during remarkably difficult times.

It’s highly gratifying to see it in print and widely available again, and again, I experience that joy on a personal level. Sherlock Holmes says (very rightly, too) that when a doctor goes wrong, he is the first of criminals—he has the training, intelligence, and foresight to plot all sorts of dastardly deeds. Well, I will go so far as to say that when a reader goes rogue, he or she can potentially become the best of writers. Starrett penned what he did for love of a ripping yarn, without blushing or prevaricating or gatekeeping of any sort, wanting only to give his audience a chance to escape the reality of their lives for a little while. What a lovely goal. What a timeless one.

It would be completely hubristic to fantasize that we might have been pals if Vincent Starrett were around today. But it’s perfectly safe for me to admit that I want to be him when I grow up.

***