Upon assuming power, the leader of the Bolshevik Party, Vladimir Lenin, envisioned the film industry as a valuable resource to promote class consciousness and worker solidarity in support of the new regime and communist ideology, famously stating that “the cinema is for us the most important of all the arts.” In that sense, his vision was entirely utilitarian. Foreign imports and new entertainment films meant to raise revenue, and other genres included depictions of people from all countries in order to inculcate the Soviet people with a genuine sense of internationalism.

However, for the first half of its existence, horror films were taboo in the Soviet Union. One reason is that Anatoly Lunacharsky, as People’s Commissar for Education, advocated for melodrama as an art form to combine education with entertainment for the people. Even though he co-authored the 1925 film Medvezh’ia Svad’ba [The Bear’s Wedding], broadly categorized as horror, its plot and techniques borrowed from pre-revolutionary cinema more than offering something new, and the horror aspect was dialed down. Another reason is simply ideological: toward the end of the New Economic Policy, which permitted a limited market economy, and particularly in the early years of Stalin’s ascent, major film makers perceived horror as overly fixated on personal psychology and ignorant of class and social issues. The superstitions and promotion of the paranormal not only pushed against the Soviet stress on atheism, but it also promoted violent and reactionary ideas that denigrated the effort to construct a new, future oriented, socialist society built on mutuality and socialist realism. A vampire’s aversion to the cross meant nothing in a society that did not officially believe in sanctity.

Horror did not really re-enter into conversation until the late 1960s, with the release of Viy in 1967. With the state’s turn toward satisfying consumer production after World War Two, the film industry gave more attention to commercial considerations over rigged ideological orthodoxy. The ninth five-year plan of 1971-1975 clarified the economic failings of the country, and the State Committee for Cinematography sought to exploit the emergence of consumer culture to raise money. Part of that strategy involved importing foreign films, giving domestic producers competition, and improving the creative output of Soviet films. This led to a veritable boom in film production, but not all films were treated equal: some were released for popular audiences, and others were shelved for crossing ideological boundaries. The film industry had its hands tied by a realist knot.

Thus, what makes the period of glasnost [openness] and perestroika [restructuring] so integral to the history of Soviet cinema, and yet so paradoxical, is that it saw initiative for industry change emanate from the Party, rather than from the industry itself—the knot was finally released. Granted, members of the film industry sought and lobbied for changes well before perestroika but change only came when the regime considered it integral to its reconstruction campaign. The process of cultural decentralization, initiated under Mikhail Gorbachev’s leadership, released pressure from decades of suppressed creative talent and Party ideological control. Films that struggled to make waves before perestroika, like surrealist films and those seriously addressing youth issues, finally broke through after 1986. In May of that year, at the 5th Congress of the Filmmakers Union, three-fourths of the leadership was replaced by progressive members not promoted simply by Party bureaucrats. When controversial director Elem Klimov (who’s first film [Welcome, or No Trespassing] was banned as an insult to the USSR in 1964) became head of the Union, replacing the conservative Lev Kulidzhanov (led 1965-1986), spectators hailed it as a triumph, even though the decision was still heavily influenced from above. Major studios like Lenfilm also sought to reinvigorate the studio with artists and directors to encourage personal initiative in creating innovative motion pictures, which, it managed to do with horror films like P’iushchie krov’ [Bloodsuckers]. This new progressive leadership paved the way for the diversification of the Soviet film catalog, opening the possibility for genuine horror films. Not everyone liked the new developments, with one conservative film commentator noting that “the [horror] genre has become fashionable because irrationalism has become fashionable.”

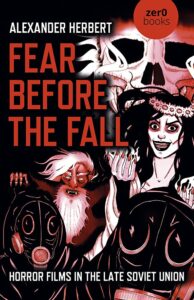

My book, Fear Before the Fall: Horror Films in the Late Soviet Union, uses horror films from 1967-1992 to reflect on the course of Soviet history. Beginning with the 1967 film Viy, which used a folk story by imperial-era writer Nikolai Gogol to reflect broadly on the moral bankruptcy and gluttony of consumerism, I trace several fears and anxieties that weighed on the minds of late-Soviet people. Vampires that signify generational tensions and female promiscuity, technology that heralds the apocalypse, and werewolves that signify the permanence of transformation are just a few of the themes that emerge from the study.

Horror more than any other genre strikes at the heart of our fears as humans and thus provides a lucid framework for studying late Soviet culture and society. Horror films are perhaps the most capable of demonstrating the power of the moving imagine because they intentionally manipulate the emotions and experiences of the viewer by toying with something psychologically innate in human nature—fear of death, dying, change, and the unknown. The primary question of my book then is precisely what scared people most in the late Soviet Union?

***