“Hamburg is a giant counting house by day, a giant brothel by night,” satirist Heinrich Heine quipped a good two hundred years ago, in a mordant description of the Hanseatic city’s two defining poles: its free trade and its permissive nightlife. Behind any ridicule lies the reality of the city as a place of economic, moral, and social contrast, one that persists into the present day.

Or as Ingvar Ambjørnsen once wrote, “Buying and selling, I thought. That’s what it all revolved around. And I thought of all the people who had nothing to sell and therefore nothing to buy, but who kept their grip nonetheless, neuroses blossoming and psychoses vivid as ever” (The Mechanical Woman, 1991).

When Saxon settlers built the Hammaburg fortification at the edge of the known world in the eighth century CE, they did so in a prime geographical location nestled in between the Alster and Bille rivers, with the Central Eastern European hinterland behind and the Elbe in front—the powerful river that would prove the lifeblood of the city and guarantor of its rise.

Soon a busy trading center, the town developed slowly at first, then with increasing speed throughout the Middle Ages. With the founding of Neustadt in 1188 and the construction of the port, Hamburg became the engine of the Hanseatic League alongside Lübeck, the primary outlet to the North Sea and Western Europe. By the end of the eighteenth century it was Europe’s trading post, a critical center of maritime commerce linking every corner of the earth.

In an era before commercial air travel, Hamburg was quite literally Europe’s gateway to the world. Anyone from Northern Europe looking to strike out for distant lands or the New World on the far side of the Atlantic had to start from Hamburg, creating a cosmopolitan melting pot of different cultures and lifestyles from early on. Today, nearly forty percent of Hamburg residents trace their roots back to one of more than 170 countries.

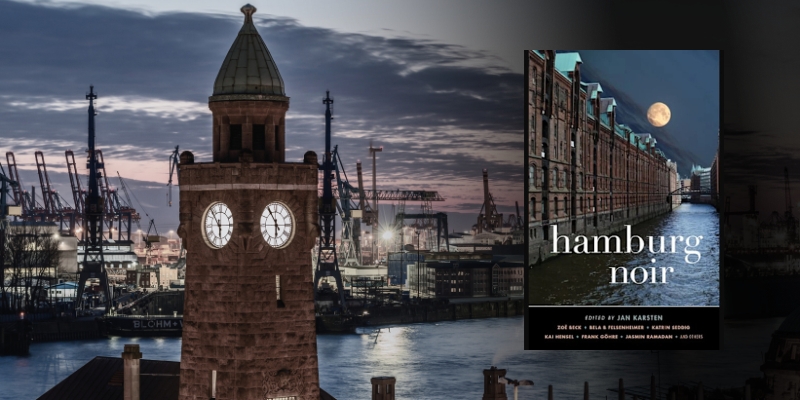

The Port of Hamburg continues today as one of the world’s busiest; the ships and cranes, teeming crowds and shrieking gulls, and the sounds and smells of the shipyards, unloading docks, and warehouses have always been a fixture of the city’s identity. It is a location that has undergone one incarnation after the next, from the cog ships of the Hanseatic League to the tall ships and general cargo vessels of yesteryear, to the monstrous container ships of our time.

At present, a new chapter in the city’s history is being written with the HafenCity project, built around the €866 million Elbphilharmonie.

That is one side of the city, at least as it appears in the glossy tourist brochures: the panoramic view of the harbor from the landing piers; the distinctive Kontorhaus district, a UNESCO World Heritage Site along with the adjacent Speicherstadt district; the gaudy department stores around Binnenalster, the glittering lake in the heart of the city; and the red-light clichés of St. Pauli.

Hamburg Noir prefers to explore some of the city’s less illuminated districts, out beyond the superlatives like the “most beautiful city in the world” that Hamburg likes to pin on its lapel.

It isn’t that Hamburg has an exorbitantly high crime rate; the index lies somewhere in between Chennai, Melbourne, Bangkok, and San Diego. Yet crime has never been the exception to the rule, but an integral, and perennial, element of the city’s history.

There is the callous reckoning of the city’s power brokers; the black market activity and countless sorts of smuggling one would only expect from a city of trade (as recently as 2021, sixteen tons of cocaine with a street value of nearly €3 billion were discovered here, in Europe’s all-time largest haul); and last but certainly not least, the everyday crime that typically plays out below the threshold of public perception, whether related to drug trade and procurement or the turf wars of organized crime—not only in the red-light district.

Then, of course, there are the all-too familiar companions to a human life: the obsessions and fateful decisions we arrive at out of love, greed, jealousy, misery, necessity, despair, hatred, or anger.

For Hamburg has always been a place for the stranded—sailors no longer in service, lost souls, failed soldiers of fortune, windmill chasers. By the Middle Ages the city had already come to be defined by social contrasts: wealthy ship-owning dynasties and affluent merchants on the one hand; mass poverty, hunger, and misery on the other.

The divide meant the wars and disasters of the early modern era hit the poor especially hard, as in 1806, when the French occupation forced any city resident unable to demonstrate at least four months of provisions to leave, ultimately halving the city’s population through flight or death.

Or in 1892, when a cholera outbreak claimed more than 8,500 victims in what was then Europe’s largest slum district, the Gängevierteln, where people lured to the city in the hopes of a better life subsisted under medieval conditions.

Still, amid all the crass inequality Hamburg has largely responded to its disasters with a mixture of pragmatism and resilience. When the Great Fire of 1842 destroyed a third of the city center, including the town hall and St. Nicholas Church, the resulting push for modernization brought the wide streets and modern construction that help define the city center to this day.

It would take all of the city’s powers of resilience and determination to survive and rebuild in the wake of the devastating bombing raids of World War II. Over the course of ten days during the summer of 1943, more than 34,000 people died in an unparalleled series of attacks from British and US planes.

The firestorm that resulted from “Operation Gomorrha” obliterated half of Hamburg’s housing stock, reducing entire neighborhoods to apocalyptic, rubble-strewn scenes; only the tower of St. Michael’s Church emerged unscathed. Anyone looking at the pictures from the era would hardly believe that in just fifteen years Hamburg would have reestablished itself as a bustling metropolis.

Yet throughout all the demolition, rebuilding, and construction, Hamburg retained its unmistakable character. Now as then, the spires of the city’s five chapter churches still mark the city skyline, in part since hardly anything has been built that’s taller than the 132-meter spire of St. Michael’s, following an unwritten but ironclad rule.

Today Hamburg’s industry and economy still place it among Germany’s richest regions, the place where the greatest number of the country’s millionaires call home. The distribution of that wealth is disproportionate in the extreme, as is visible from the sea of faces the city presents: the sea captains’ homes and the villas looking out onto the Elbe in Blankenese; nearly rural suburbs; socially restive areas south of the Elbe and to the northeast, in parts of which every other child lives below the poverty line; the crowded urban scenes of Altona, St. Georg, and St. Pauli.

*

The many facets of Hamburg’s ambivalent identity, forged over centuries, are on full display in the stories collected in this anthology. Here, we have assembled some of the city’s finest and best-known writers, luminaries in the world of crime fiction and German literature, featuring multiple recipients of the German Crime Fiction Award and the Hubert Fichte Prize, among others.

Relative newcomers rub shoulders with established authors, some of whose work now spans decades, like Ingvar Ambjørnsen, who first came to Hamburg from Norway in the mideighties. Many of Ambjørnsen’s novels give voice to societal dropouts and petty criminals, the prostitutes and the drunks, depicting their worlds as empathetically as they do unsparingly.

Writers like Frank Göhre, a towering figure in German-language crime fiction whose work condenses reality and fiction into rapid-fire, highly associative, dialogue-rich studies of society. Taken as a whole, Göhre’s evocative settings provide a sort of counterchronicle to the Hanseatic city that spans decades, laying bare time and again how tightly political and economic power are interwoven, and petty criminality with more organized crime.

Nora Luttmer walks us through Rothenburgsort, a diverse, industrial area in the city where Auntie Lien runs her small Vietnamese restaurant—until a bull-necked extortionist threatens the intricate social web that exists between Ghanian traders and Senegalese day laborers, between the Afghan market and snack bars and the Lebanese import-export shop.

Jasmin Ramadan shows Hamburg’s immigration as a process of daily arrivals. Fresh from Sudan on an art stipend and searching for the vanished woman whose apartment she’s been allowed to stay in, Ramadan’s protagonist discovers family in an unexpected place: a local bar in Eimsbüttel.

As a port town, it’s no surprise that pubs are a mainstay in Hamburg; the bars and hot spots, notorious dives and drinking dens, are often open along the piers or on the block around the clock, at times providing the only constant in the lives of their patrons. As in Tina Uebel’s requiem for the Clochard, a neighborhood institution where people with nowhere else to call home find one, but which didn’t survive lockdown during the pandemic.

It isn’t bars alone that set the pace and rhythm of the neighborhoods. Aside from its parties, Hamburg has long had a thriving music scene, home to Johannes Brahms and the Beatles and now featuring the world’s third-largest concert hall, drawing massive crowds.

Yet over recent decades it’s been the many small clubs (not just around the Reeperbahn) that have largely set the tone for the musical underground, whether swing—under mortal danger during the Nazi era—jazz, rock and roll, punk, avant-garde pop, or hip-hop.

Fittingly, two contributors to this volume have been well-known as musicians for decades. Bela B Felsenheimer delivers a tale full of gallows humor about small-time dealers and bouncers in St. Pauli, with a problematic character named “Rocken Roll” leading the charge. Timo Blunck stages a “Grusical” deeply rooted in the city’s history, parodying Hamburg’s reputation for musicals, serial-killer novels, and the middle class’s new fetishization of cooking, all in the same breath.

Brigitte Helbling explores the ways in which seemingly harmless encounters can mushroom into greater and greater threats, introducing us to aikido as an art form for dealing with danger, even in completely unexpected ways. In Kai Hensel’s coming-of-age story, set against Hamburg’s triannual carnival, an encounter between two teens leads to the unnerving discovery that it isn’t always wrong to commit a crime.

In “The Assignment,” Katrin Seddig sets out to capture the city’s essence by literary means, having her heroine stroll through an almost expressionist cityscape of hellishly loud arterial roads, disrepair, and vast construction sites. As the “new, shiny, and clean” blots out and overwrites the “old, boggy, and overgrown,” it echoes the ruins of the past: the “essence” of the city is “lethal.”

Seddig’s story is also a clear-eyed chronicle of gentrification as the constant companion to a city forever at war with itself over who should get to determine a neighborhood’s profile: the people who live there or the investors and real-estate speculators yet again.

Till Raether cooly narrates the demise of a captain of modern finance who runs his private equity firm aground gambling on crypto currency. The sharp turn in fortune leads the loser of the bet south of the Elbe, to the less glamorous corners of the industrial port behind Europe’s most modern shipping-container terminal, where people live in condemned warehouses, in the forgotten, in-between sections of the city.

The water is never far off in Hamburg, no matter where you end up in the city. Matthias Wittekindt’s protagonist Manz, a young police officer in the 1970s, is charged with investigating an attack on a young woman found dead in a small branch of the Elbe east of the city center. The trail leads to a nearby hang-gliding club, where the old guard of the Hanseatic elite spend their weekends.

Robert Brack takes us even farther back into the past, to the Altona of a hundred years ago. Still an independent borough at the time, Altona was a bedroom community for the workers who toiled in Hamburg’s factories under difficult conditions to process the tobacco and other wares that flooded unceasingly into the city through trade.

In vivid, concrete prose, Brack writes about cigar rollers and cigarette stuffers, an ill-fated romance in patriarchal times, and a restive worker population who finally get enough of the daily drills on the “parade grounds of capitalism.”

The fourteen stories in this collection all look to where good (crime) fiction has always looked: toward lesser-known settings and living situations, repeatedly drawing our attention to lives overlooked, the lost souls and the powerless who have slipped through the cracks of commerce.The degree to which class tensions still determine individual fates in the present day is on glaring display in Zoë Beck’s contribution. Against the backdrop of the exclusive Elbchaussee and Hamburg’s yacht marina, Beck shows us the corruption of Hamburg’s modern business elite, as superficial as they are debased, in a sparkling minidrama that wickedly but casually brings home money’s perennial ability to make every last problem disappear and destroy entire lives.

The fourteen stories in this collection all look to where good (crime) fiction has always looked: toward lesser-known settings and living situations, repeatedly drawing our attention to lives overlooked, the lost souls and the powerless who have slipped through the cracks of commerce.

The perspectives on the metropolis are as diverse as the writers’ backgrounds, resulting in a varied depiction of Hamburg as a colorful hodgepodge of people inhabiting a lively city of millions. Between water and spirits, between power and oblivion, between dream and reality.

(Translated by Noah Harley)

***