Dracula is the most powerful adaptation fad in recent times. The count has sprung alive in incarnation after incarnation for approximately a century, without totally dying out.

The Guinness Book of World Records counts Dracula as the most-played character of all time. The Internet Movie Database lists on its website hundreds and hundreds of projects in which the character Dracula has appeared since 1917, when an unauthorized (and as far as scholars know) lost Danish film called The Death of Dracula appeared. (It is unknown whether or not it had anything to do with Stoker’s novel.)

Of course, there have been other textual traditions with long, healthy histories of appreciation and adaptation, especially for film and television—Hamlet (or many others from the Shakespeare Folio), is a good example of this. However, there is a marked difference between the performance tradition of a dramatic work such as Hamlet (something that was written to be staged) and the performance tradition of a work that had to be turned into a performable version first. Dracula was not originally adapted due to its popularity, but, as I and others have written, was adapted, as part of a plan to preserve and expand the power of Stoker’s novel (and bring in more revenue for his widow, Florence).

The fact that it has been accepted heartily in several media and many versions over a century reveals that is still in demand. It was a very successful book. It received favorable reviews. As Dracula scholar David J. Skal quotes from American literary journal The Bookman, “from the very first its sales were enormous, not only in the States, but Canada, also.” In 1912, the publishing company William Ryder and Sons released a new edition, which would remain in print for more than forty years. (Perhaps the only other long-lasting twentieth-century franchise to rival both multifariousness and heterogeneity of Dracula adaptations is that of Superman—while there are more live-action film, television, and stage adaptations of the former than the latter, the vast plethora of Superman comic books and television cartoons greatly exceed both in amount and in popularity the animated avatars of Dracula, the likes of which include the Count Chocula cereal logo, and the British cartoon Duckula.)

The tremendous frequency with which Dracula has been adapted since 1922 has led to something more significant than simply a plethora of Dracula versions, however: it has resulted in many different stories about Dracula. And this is “the problem with Dracula adaptations” that I found: the Dracula adaptation canon is replete with grandiose textual infidelity.

But why is this a problem? Is it even a problem? In his essay “Adaptation, or Cinema as Digest,” André Bazin argues that the actual problem of adaptation is the paradox brought on by misconceptions of both the purpose of adaptation and the necessity of fidelity; nothing can truly be adapted faithfully without being considered a reproduction, and when something is fully reproduced, it cannot be an adaptation. Still, making changes that facilitate a textual version’s formal transformation into a cinematic one does not seem to be the system behind many of the specific changes made during the dozens of times Dracula has been brought to the screen—such as the addition of romances. The problem I have found is that many of these adaptive changes are not necessarily in line with what Bazin advocates. The objective he champions is capturing the spirit of the original work. However, many films name themselves after Dracula without adopting many of the facets of the novel’s ethos.

Is this important? No. Do I want an accurate Dracula film anyway? Yup.

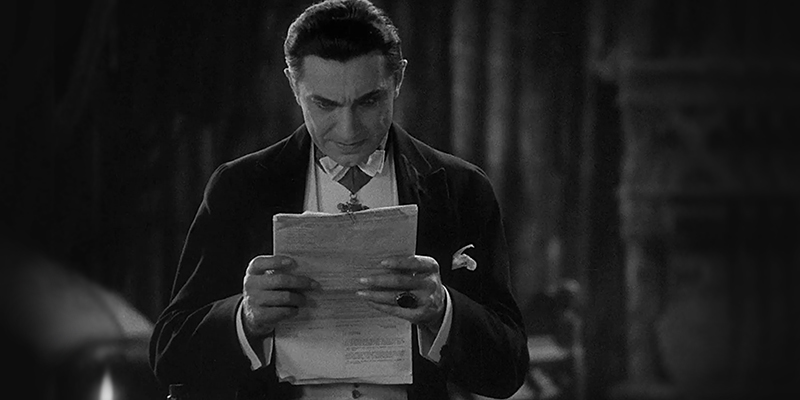

It’s insane that there hasn’t been one yet. How could it be, I wondered after watching many of the major films, that an adaptation canon with so many films to its name could not feature even a single one which told the story that the book did? And it’s not just any book—it is an extremely popular, significant book. In the 1931 Tod Browning Dracula, with a tuxedoed and thoroughly foreign Bela Lugosi as the eponymous vampire, Renfield is the solicitor who arrives in Transylvania, Seward is Mina’s dad, and Lucy’s function has been given to Mina. In the 1958 Horror of Dracula, Dracula is a taciturn English aristocrat, and Jonathan Harker is a vampire hunter who heads to his castle to kill him. When this backfires, Holmwood and Van Helsing team up to save Lucy, Dracula’s next victim. The 1979 Frank Langella film is very similar to the Browning film, except Dracula is now a Byronic lone wolf who shares with Lucy (in Mina’s role, sort of) a forbidden love.

One of the more faithful Dracula films I had encountered was Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 Bram Stoker’s Dracula. I had considered this as a solitary, loyal exception because all of the characters from the novel that were often written out or combined with others in many Dracula versions are fully intact, in this film. However, this same version also situates in the film’s exposition a Medieval vampire origin story involving an Ottoman invasion, and adds to the main plot a love story between Dracula and Mina, the latter of whom is apparently the reincarnation of Dracula’s dead wife.

So, then again, maybe not.

My quest to find a loyal Dracula adaptation proved successful when I came across a version that had been written in 1897, by Bram Stoker, himself, and was published for the first time one hundred years later. During a century in which Dracula had exploded in popularity, and had many famous incarnations, it turns out that the author was the only man to ever closely adapt the novel. Interestingly, though, this produced a complicated, clunky derivative that, after it was staged one time, was never performed again. And for good reason. It’s terribly boring, and was most likely written for to give Stoker a copyright against any pirated stage adaptations, not for any narrative investment.

The thing is that Dracula might simply be un-adaptable, too cumbersome and complicated to be brought to a streamlined cinematic narrative. But I feel like now we’re not even trying.

Most Dracula adaptations now seem more interested in exploring the character’s cinematic afterlives than returning to the whole text: Renfield was a weird re-animation of the Universal StudiosDracula IP that then went off the rails. Robert Eggers’s masterful Nosferatu explored the schism in adaptation history between Dracula and Nosferatu movies. I found The Last Voyage of the Demeter, which promised to bring to screen the one scene from the novel Dracula that is almost never given screentime, a creative endeavor, but more of a side-project.

It feels like we’re mired in postmodernism a little too deeply to return to the text of Dracula, and that’s fine. But I long for the day a filmmaker gives us a film that responds to the book, and only the book.