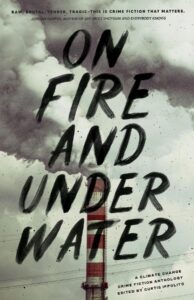

The new anthology On Fire and Under Water sets out to show how devastating the effects of climate change are for everyday people. Discuss the growing urgency of the climate emergency and the ongoing dismantling of environmental protection efforts.

C.W. Blackwell: There is no greater emergency than the climate crisis. All of the fundamental political rights we are fighting to protect are meaningless if we are literally on fire and under water. In a post-apocalyptic world, there is no guarantee of any rights at all. The one percent know this and are building bunkers and hoarding resources to ensure their reign as Kings of Armageddon. Don’t you dare let this happen—fight it with everything you have.

Richie Narvaez: Our current times have totalitarianism, widespread economic disparity, oh, yes, and genocide. Plus, racism, sexism, rise of AI, et al. But none of that can be resolved in any way if we don’t have a planet. Every passing day without real action from governments and corporations is another step closer to doom. I know our culture expects upbeat endings and “Everything will be okay” messaging. But I don’t see any rainbows ahead. Unless you count ones arising from giant oil slicks in the ocean.

Kendall Brunson: The climate crisis is also a humanitarian crisis. In Florida, state and federal governments are running roughshod over environmental protections in the Everglades to service their agenda. A judge ordered the South Florida Detention Facility (aka Alligator Alcatraz) to close because it was causing irreparable damage to the fragile ecosystem, but that damage to the Everglades and the immigrants being held in the prison is ongoing. We can only hope the courts enforce the rule of law to stop the destruction and continue to fight back, for both the people and the ecosystem.

Puja Guha: When I worked in East Africa, I thought Typhoon Idai was the worst climate change could deliver. But then earlier this year I visited Jasper, Alberta, and saw the devastation from the fires last year. Since then, the Los Angeles and Manitoba fires have been even worse. The devastation is beyond comprehension, and I feel as if humankind could be too late to put a stop to climate change.

Edward Barnfield: I hit 50 last year, and the discussion of climate change has been a constant throughout my life. And so, alongside watching the numbers get worse—2024 was the hottest year on record and 2025 looks like it might beat that—I’ve known the situation is deteriorating rapidly. It’s fascinating and maddening to watch the coordinated reaction against even the flimsiest environmental actions. Protections for forests and wetlands are being torn up, and we’re deluged with misinformation against anything other than the status quo. It feels like a generational failure to confront the issues, supported by a spasm of nihilistic consumerism that could function as our epitaph.

What role do you believe fiction and storytelling have to play in regard to this emergency?

Priscilla Paton: Stories sound alarms. Stories connect. Stories empower. It’s difficult to grasp the scope of climate change without being overwhelmed or numbed. In my story “Ice Out,” warming temperatures and misuse of land threaten a Maine family’s economic survival, their autonomy, and their sense of belonging to a place and its culture. Stories such as these in the anthology entertain as they frame the issues to reveal personal connections, costs, and knowledge.

C.W. Blackwell: Seeing drone footage of flooded towns or fires raging through hellish landscapes makes an impression—but for some, it can also feel distant without seeing it directly through the eyes of folks closest to the tragedy. Fiction enables us to understand tragedies in their context, within full view of a survivor’s hometown, their loved ones, their sense of identity and their histories. Understanding a character in this way helps us to build empathy—and hopefully empathy will become action.

C.E. McKenna: Reading fiction is a form of experiential learning; it allows us to imagine scenarios before we encounter them. To some, reading about the fictional devastation of climate change might underscore how immediate and worrisome the future is and cause them to change how they live today. For others, it might give them the ability to think through how they would approach a similar situation. In my story, “Long Night of the Polar Bear,” which I set on the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, I wanted to take readers to a setting they might be unfamiliar with—a wild place, populated by more polar bears than people—and investigate what it feels like when an environment doesn’t behave the way you expect it to.

Mary Thorson: I’m a born and bred journalist. I switched careers after I had children, but my parents were both journalists, my siblings, and me for about ten years. Storytelling is the only way to move the needle. And it moves it so little, but it’s the only thing that moves it at all.

Richie Narvaez: Fiction is unlikely to change anyone’s mind. No one who thinks climate change is a hoax is going to pick up an anthology like this. Or any anthology, probably. So what we’re doing here, as the saying goes, is preaching to the converted. But there is value in that because we are reassuring each other that this problem is imperative and hopefully keeping each other riled up enough to keep working to do something, even when things feel hopeless.

Edward Barnfield: Even if fiction can’t shift the narrative on climate responsibility, it’s important to mark this moment and people’s response to it. The analogy I draw is Western literature in the 1930s, where a handful of writers (mostly exiled Germans) try to warn of the rise of Nazism, and the British writers were mostly focused on ballrooms and nonlinear storytelling. There’s a responsibility to confront the most pressing issue of the day and try to leave an honest account for readers in the future.

Puja Guha: I believe fiction and storytelling are powerful tools to raise awareness—both on the existence of climate change, but also on the scale of its impact. Throughout my life, I’ve learned so much about history, culture, and the vastness of human emotion from fiction. My hope is that fiction like the On Fire and Under Water anthology can help more people understand the importance of this issue and how it impacts everyone, all over the world.

What was most important thing for you to show readers about this moment in our planet’s history, seen through the eyes of your main character(s)?

Kendall Brunson: In “Bad Egg,” Angel truly believes there is no action too small. Individual effort still matters. Every native species saved and tree protected or planted is an act of resistance. The most devastating thing we can do now is believe it’s too late and give up. Apathy is dangerous.

Meagan Lucas: The thing I was grappling with most while I was writing “What You Lost” was the idea that these emergencies don’t happen in a vacuum. They happen when you’re already having a terrible day/month/year. That in our collective ignorance and greed we are making our already difficult lives worse.

C.E. McKenna: Any story I write about climate change has a kernel of hope in the face of hopelessness. That hope comes from zooming out to the global level and knowing that this is neither the first apocalypse, nor will it be the last. Earth has gone through billions of years of changes that wipe out species and forge new ones. That’s the story of this planet. This realization—that individual humans are part of a much larger geological and ecological history—is something my main character, Atle Solås, discovers at the end of “Long Night of the Polar Bear.” It’s a concept that brings me, Atle, and hopefully our readers, a small sense of peace.

Edward Barnfield: My story, “Marching to Jerusalem,” is about an earlier generation of activists, and the extent to which state power was used to crush them. That’s still a constant now—if anything, the situation is more extreme than it was. At the core, it recognises there were and are very human failings at the heart of the environmental movement—errors of tactics and politics, organisational mistakes, etc.—but that those are of much less consequence than the fact that successive governments decided to use any means necessary to defeat it.

C.W. Blackwell: For me, the fact of the environmental catastrophe is one thing, but the human reaction to the impending chaos is another. I wanted to show in “Poison is the Wind that Blows” how corrupt, rapacious, and immoral humans will behave when shit hits the fan, and how it will be up to a select few to hold the line between possible redemption and full-blown authoritarian kleptocracy. Better yet—let’s stop it from happening at all. There’s still time, but we’ll have to start yesterday.

Priscilla Paton: Like many of us, teenage Becca feels overwhelmed, frustrated, and distrustful in the face of climate change and financial and political bullying. She fears that her Maine Guide family will be punished for protecting resources and that the native beauty around them will be ruined. She seeks agency, as do we all. Desperate for that agency, she commits to a desperate act. What “saves” her in the story is family knowledge of their bit of nature, insight into the “enemy,” and canny thwarting of strongarm tactics.

If you could eliminate one symptom of climate change, what would it be?

Meagan Lucas: Selfishness. Specifically, the selfishness and apathy of the developed world who have decided that they have the luxury to not believe scientists because they don’t live below sea level, or because they have the money to rebuild and relocate. It’s gross. We’re stealing from our children for some short-term comfort, and it makes me ill. What happened to our grit?

C.W. Blackwell: Apathy. I want people to be single-mindedly focused on solving this crisis at all costs, even if it means major short-term sacrifices. I’m not rich by any means, but I’d gladly pay double at the gas pump if it meant avoiding a world of ash and suffering for future generations. We need the will and resolve to tax oil companies into oblivion in order to foster a clean energy revolution. Oil and gas companies are akin to the ghoulish tobacco companies of yesteryear—how can anyone not see this?

Priscilla Paton: Gosh, the rise of devastating storms which result in loss of human life, animal life, and terrain. Then again, there’s species extinction—a world without polar bears?

Kendall Brunson: Habitat loss and protecting as many native habitats left on Earth as possible. The Everglades are less than half the size they used to be because of government intervention, agriculture, and urban development. Where I live in Northeast Florida, we recently fought to prevent a developer from buying and destroying 600 acres of the Guana Preserve, and last year, Floridians fought to keep the state government from turning state parks into golf courses with hotels. But Florida still loses roughly 120 acres a day to development. We need to keep what remains and try to rebuild what we’ve lost.

Mary Thorson: Asthma. Specifically, the socio-economics causation of asthma.

Puja Guha: Summer heat! Instead of the occasional heat wave, I now feel like the entire summer is just one long heat wave. Air conditioning is becoming more of a necessity in places where you could easily have gone without a decade ago.

C.E. McKenna: If I had a solution to keep the polar ice from melting, I would enact that immediately.

Edward Barnfield: I’d quite like to solve accelerated cryosphere decline and coral bleaching, but I don’t think the answer to either is going to be technological. In truth, I’d remove the false equivalence, where every new fact about climate change is countered in the media by a contrarian voice recycling old arguments and conspiracy theories. It’s more of a cause of the crisis than a symptom, but, God, I’d like it gone.

Richie Narvaez: Belief. Belief that climate change is real. Belief that our home is worth saving. Belief that we need to constantly be working to keep it livable for everyone.

***