There was a time when TV, after decades of square-jawed, ramrod straight cops and two-fisted private investigators, decided to shake things up and give the public some unusual and unorthodox investigators.

Because this was the late 1960s and early 1970s, this typically meant only that those investigators were shaped differently than the run-of-the-mill TV detective.

So we got older detectives (“Barnaby Jones”) and heavyset detectives (“Cannon”), cops in wheelchairs (well, just one: “Ironside”) and a few others.

But the stories were the same ones told in their predecessor shows because … well, it was TV a half-century ago.

Many of the shows followed the formula established by “Lassie” in 1954, believe it or not, and perfected in four seasons of “The Fugitive” beginning in 1963: Wandering stranger comes to a small town and gets involved in the strife-filled lives of people there—all the while being pursued. Heck, even “The Incredible Hulk” came from the same mold.

While the TV networks usually played it safe regarding unconventional mystery-solvers, there were some truly offbeat investigators. The most unusual of them were featured in short-lived shows, because in most cases, the broadcast networks (and viewers, to be honest) didn’t know what to do with shows about investigators whose greatest mystery was … themselves.

‘Longstreet’ was the coolest of the cool

You know those “Sure you’re cool, but are you FILL IN THE BLANK cool?” memes? They’re all half-baked jokes compared to “Longstreet,” thanks in part to the presence of martial arts legend Bruce Lee.

Created by Stirling Silliphant (Oscar winner for his “In the Heat of the Night” screenplay), “Longstreet” had a long life compared to other offbeat detectives: Twenty-three episodes on ABC from September 1971 to August 1972.

In that single season, “Longstreet” introduced Michael Longsteet, probably the country’s best insurance investigator, who’s married and living in New Orleans. In the pilot, a bomb planted in a champagne bucket—don’t laugh, they stage it well—kills his wife and leaves him blinded.

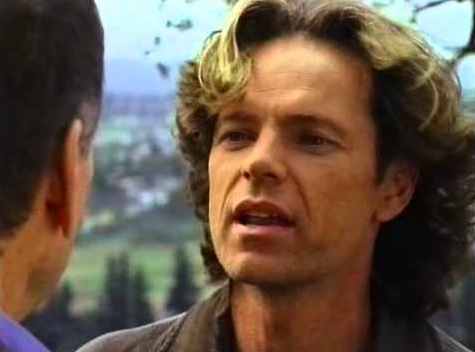

As played by James Franciscus, Longstreet is at first single-minded in his determination to, despite his blindness, identify and bring to justice the men who killed his wife.

Initially the insurance investigator pretends to make progress in his emotional recovery just to be able to work on the case. But ultimately, Franciscus’ character acknowledges he must genuinely want to reconcile his new circumstance with his changed abilities.

As a sighted person watching the show as a kid then and as a discerning (hopefully) adult now, it seems to me that “Longstreet” got a few things right. One of them is its no-nonsense treatment of Longstreet as something very much other than a “Daredevil”-style superhero. He’s physical and fairly daring but his intellect is what solves the mystery in each episode.

Often, he’s not even on hand when the police catch the bad guys. Longstreet notes that he doesn’t have to be there for the bust, because he’s already resolved the problem in his head.

Lee, who appeared in four episodes as Li Tsung, was a rising star after having appeared in “The Green Hornet” and a series of hit martial arts movies in Hong Kong. Lee’s frustration at not being accepted as a leading man in Hollywood, especially in TV, is well known.

But hopefully he felt some satisfaction in “Longstreet,” because it’s obvious his quiet presence is the highlight of every episode in which he appears.

Lee coaches his student through not only basic moves but mindfulness. He’s not just there to instruct; in one episode, he kind of hangs out, joining the team with Peter Mark Richman as Duke, Longstreet’s insurance company boss, and Marlyn Mason as Nikki, Longstreet’s assistant.

Lee and Franciscus, as well as the scenes actually filmed in New Orleans, elevate the series and make me wish it had a long run.

‘Coronet Blue’ was a mystery never solved

When it debuted on CBS in May 1967, “Coronet Blue” offered one of TV’s most intriguing mysteries centering on its lead character. It’s too bad the mystery was never solved. At least on the air.

The series was dead on arrival by the time it aired. It had been filmed two years earlier, in 1965, and had never been shown, so CBS was “burning off” its investment during the summer months of 1967. Only 11 of the show’s 13 episodes aired before its September 1967 finale.

Its star, Frank Converse, had already been cast in another series, “NYPD,” that began airing a few days after the last episode of “Coronet Blue” aired.

But was the show’s central mystery, the true identity of Michael Alden—the lead’s adopted name—ever solved? Creator Larry Cohen, later best known for offbeat movie thrillers like “It’s Alive” and “Q the Winged Serpent,” said in a 2007 interview he knew the answer: Alden was a Russian spy, planted in the United States as a sleeper agent. But Alden—real name apparently “Gigot,” as he’s referred to once in the first episode—wanted to defect. That’s why his fellow Soviet spies tried to kill him in the first episode and menaced him throughout the series.

‘The Immortal’ was … not

The premise of the 1970 TV series “The Immortal” sounds like a comic-book plot in some ways: A racecar test driver donates a pint of blood to his billionaire boss and the rich man discovers the blood is a miracle drug that, with repeated transfusions, can convey immortality on whoever receives it.

Star Christopher George’s character—named Ben Richards, perhaps after two of the “Fantastic Four?”—won’t age and won’t die, unless he is killed. Richards must go on the run to stay out of the clutches of a series of billionaires, who hire bounty hunters to find him and bring him back for an endless series of blood transfusions.

In the meantime, Richards looks for his estranged brother, to warn him that his blood might make him a target as well.

The Fugitive/Lassie/Incredible Hulk trope is in full effect here, as Richards, sometimes hitchhiking and carrying a small duffle bag, walks around the southwest, interacting with strangers and affecting their lives.

Ben Richards might have been immortal but, no, his series was not. It was canceled in January 1971 after only the pilot and 15 episodes.

‘Nowhere Man’ was an exercise in paranoia

Today’s prestige television shows, among the best of them shows on streaming services, are not afraid to definitively finish a story line—even at the end of a single season.

The creators of “Nowhere Man,” which aired as a 25-episode series in 1995 on UPN—remember UPN?—were not afraid either.

Bruce Greenwood starred as Thomas Veil, a news photographer whose most famous work was a photo he took in South America of the hanging of four men wearing hoods.

One evening after a gallery exhibition of his work, including the photo “Hidden Agenda,” Veil finds his life erased. His wife denies knowing him, his friends have never heard of him and his photographs are credited to someone else.

For 25 episodes, Veil tries not only to get his life back, but define the parameters of the conspiracy against him—particularly when it turns out the photo he shot was really of the hanging of four U.S. senators in a remote area outside Washington D.C.

“Nowhere Man” resolved its mystery in a manner that was not the easiest to take, and watching the episodes now leaves one with an acute sense of nostalgia for a time that’s not that long ago. Smoking in a restaurant bathroom! A telephone booth! The mystery’s resolution comes on a VHS tape!

‘Barnaby Jones’ and the Case of the You Kids Get Off My Lawn

When “Barnaby Jones” debuted on CBS in 1973, Buddy Ebsen was 64 years old. It says something about TV’s youth orientation that the selling point of the show was that Ebson was so old! He was the first elderly TV detective!

The Associated Press referred to the detective as—gulp—a foxy grandpa!

Newspaper coverage of the series’ debut also noted that this was a chance for Ebsen, a Hollywood staple since the 1930s, to shake the image of Jed Clampett from “The Beverly Hillbillies.” Ebsen must have done that, because “Barnaby Jones” ran until 1980.

The premise of the series: Jones came out of retirement and went back into the private investigation business after his son was killed. He teamed up with his daughter-in-law, former big-screen Catwoman Lee Meriwether, to take on bad guys. Mark Shera played a younger member of the family who joined up a few seasons in to perform more of the most physical stuff.

‘Cannon’ says if you ask me about my diet one more time …

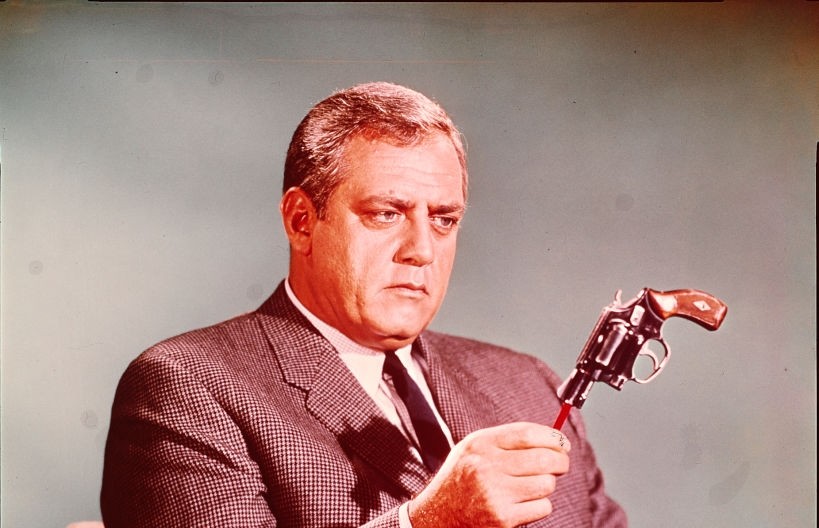

“Barnaby Jones” was actually a spin-off of the CBS series “Cannon,” which starred veteran actor William Conrad as Frank Cannon. The two series crossed over a couple of times.

The premise here was that private investigator Cannon was overweight.

That was the whole premise? In answer to that, let’s look at CBS advertising before the September 1971 premiere: “Bigger than life, that’s William Conrad as private eye Cannon. Big excitement every week.” If you’re counting, that’s two references to “big” in just one newspaper ad.

“Frank Cannon is a gruff, ruthless fat man with a heart as big as his stomach …” began the Kansas City Star’s review. Sheesh.

Conrad’s physicality, often referenced in terms of his diet and love of food, had years earlier reportedly stood in the way of his playing Matt Dillon when the classic TV western “Gunsmoke” debuted in 1955. Conrad had played the role in the original radio show but lost the TV role to James Arness.

“Cannon” ran until 1976. Conrad returned in 1987 in one of the title roles in the TV crime drama “Jake and the Fatman.”

‘Ironside’ showed that being a jerk transcends everything

Raymond Burr had already achieved TV immortality by playing ace lawyer “Perry Mason” from 1957 through 1966. But TV loves a second act for a successful star.

Debuting on NBC in 1967 and running until 1975, “Ironside” was ostensibly about a tough San Francisco police official continuing his career from a wheelchair after a would-be assassin’s bullet left him paralyzed from the waist down.

But it usually seemed to be a series about a condescending, browbeating jerk who happened to run an elite police unit.

Burr first played Robert Ironside in a TV movie that was quickly picked up as a weekly series. The series was notable not just for being led by a man in a wheelchair. Don Mitchell played Mark Sanger, Ironside’s young Black assistant who had, by the end of the series, become a police officer. Also of note was the score by composer and performer Quincy Jones, which featured a piercing siren that was later used in “Kill Bill.”

And “Ironside” sparked crossovers and spin-offs like few series until “Happy Days.” The Burr drama crossed over with two series, “The Bold Ones” and “Sarge” (with George Kennedy as a cop turned priest) and was the origin of “Amy Prentiss,” starring Jessica Walter—best known decades later for “Arrested Development”—as the San Francisco Police Department’s new chief of detectives.

“Ironside” even got a short-lived reboot in 2013 with Blair Underwood in the title role. Only four episodes aired before it was canceled, however, so the spinoff and crossover opportunities were limited.

I suspect the reboot just needed more Quincy Jones music.