One hundred miles east of Reno, Nevada, there is a town. You can’t see it from Interstate 80, the road I traveled with my husband and children twice a year as we drove from California to Idaho to visit my parents, but we stumbled upon it one day when the pumps at the Exit 105 Chevron were broken. Lovelock, it’s called. “Lock Your Love in Lovelock,” says the billboard on the interstate. As I drove from the Chevron to the Two Stiffs Selling Gas convenience store on its short main street I slowed the car. I needed to see this town in its entirety. I needed to imagine the lives of the 1,847 people who lived there, in the middle of the barren desert, so far from anyone else.

My family wasn’t surprised. They know I’ve always been fascinated by small, remote towns and the people who live in them. My parents grew up in picture-perfect Iowa towns, complete with elm-shaded streets and white-painted bandstands. They reminisced about them often, with a nostalgia that managed to ignore the fact that I grew up in the Washington, D.C., suburbs, in a “town” made up of a handful of subdivisions grouped together for purposes of mail sorting. Every summer we visited my father’s hometown, and I walked two blocks from my grandparents’ house to Dribblebee’s soda counter and swam in the community pool behind their fence. It felt like a theme park version of the perfect childhood, and every time we left I felt cheated. My parents had had that life. Why couldn’t I?

Then, when I was in high school, my mother said she wanted us to move back to Iowa, and suddenly I could imagine nothing worse than living in those cornfields, far from the malls and multiplexes of my teenaged suburban world. You’ll be Homecoming Queen, my mother promised, as though there was nothing better than being Homecoming Queen in a small Iowa town, and I realized that the nostalgia I’d always heard in her voice was really regret. She’d never wanted to leave. She’d wanted to live her whole life in the place where she’d been crowned Homecoming Queen, and to be buried in the cemetery with her great-grandparents.

But as much as he’d loved his Iowa boyhood, my father had always wanted to live in the wider world. So we didn’t go back. And ever since, I have driven slowly through small towns. I think about my mother, who wanted to stay, and my father, who wanted to leave. I think about my own internal tug-of-war: my heart is still drawn to the picket fences and slow beats of these lovely pastoral villages even as my mind revels in the kinetic energy of the large city where I’ve chosen to live instead.

Lovelock, though, was not a lovely pastoral village. It was, to put it bluntly, an unsightly scab on an already bleak landscape. The buildings in its commercial district were soulless 1970s boxes. Its businesses were the sort that cater to a struggling, working-class community: secondhand clothing stores, inexpensive diners, and a suspiciously large number of bars. The houses were small and nondescript, and there was, on the western edge of town, a rural slum that was shocking in its poverty and filth. Yet as I drove its small grid of streets its existence out there in the desert struck me as kind of wonderful, as if I’d found a secret pocket in the lining of a raggedy coat. I’d assumed the appeal of small towns lay in their quiet beauty: in grassy town squares, white-steepled churches, and graceful old homes with wraparound porches. But it couldn’t be beauty that kept people in Lovelock. Before we pulled back onto the interstate I knew I would set a story there.

***

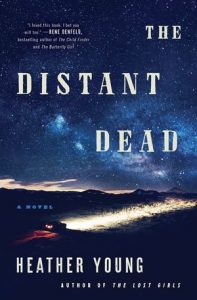

Small towns have been the setting of choice for countless mystery writers, of course. Some, like Louise Penny, create idyllic villages that they disrupt with brutal crimes that are often committed by outsiders. Others, like Gillian Flynn and William Kent Krueger, build seamier places where dark prejudices and old grudges lead to bloodshed that is all the more visceral for being so deeply personal. With The Distant Dead, the novel I set in Lovelock, I wanted to do something a little bit different. I wanted to explore the choice everyone in a small town faces when they leave childhood behind: whether to stay, or to go. How much do they value the connectedness they feel to their hometown, and everyone in it? How does that rootedness weigh against the allure of new experiences and a life filled with serial strangers? Most of all, how can the same small town offer succor to one person, and feel like a cage to another?

After that first visit to Lovelock I went back many times. I stayed in the Cadillac Inn, ate dinners at the Cowpoke Café, and drank beer at the Whiskey Barrel. The town’s seediness—its pawn shops and slot machines, its sandy lots and concrete sidewalks cooking in the sun—never failed to depress me. But I did come to see it, as best I could, through the eyes of the people who lived there.

I learned that Lovelock was once a busy watering hole on the California Trail, and saw booms and busts as silver mines opened and closed in the nearby Humboldt Range. Today it’s the Pershing County seat, serving two thousand widely scattered ranchers and alfalfa farmers. It has a sheriff’s office that hasn’t seen a murder since 1993 but investigates a disturbing number of property and drug-related crimes. There’s an annual Frontier Days fair, and a hot air balloon festival every February. It has a half dozen churches and two sandy, barren cemeteries so desolate they will break your heart. Children fish in the Rodgers Dam reservoir and ride ATV’s across the salt flats, and when they grow up, they marry their high school sweethearts and run businesses that have been in their families for generations. Or they work at the Family Dollar, the courthouse, the schools, or in the last open pit mine in the nearby hills. The horrifying rural slum is home to several hundred Paiutes and Mexican immigrants whom the white community tries its best to ignore. In short, it’s a place with troubles and pleasures that aren’t unique to it but still manage to feel distinct to its place in the world.

The Distant Dead is a mystery about a man who moves there seeking sanctuary only to die a terrible death at the hands of the demons he thought he’d outrun. It’s also about a woman who feels trapped in the town where she was born, and the fraught coming of age of a young boy, orphaned and burdened with a terrible secret, who just wants a place to belong. All three wrestle with the idea of home: what it means, how much it matters, and whether it’s ever possible to leave it and start fresh.

They stay because their people are there. Their history is there. Their dead are there.

And yes, it answers the question I asked myself when I first drove down Lovelock’s shabby main street: why stay? It’s the question I asked the bartender at the Whiskey Barrel. She married her high school boyfriend, followed him around the country while he served in the Army, then moved back with him when his tour was over. There are prettier places, she allowed. But they wanted to raise their children alongside people who’d known them since they were born. I asked the owner of the town’s only coffee shop, too. She knew the town was struggling, but her family had been there since the beginning. Leaving would feel like a betrayal. Anyone else in Lovelock would tell you the same thing: they don’t stay because they like the weather. They stay because their people are there. Their history is there. Their dead are there.

That’s also why they leave. Because for some, like my mother, the fact that the mention of their name will make everyone in their town nod in recognition is a comfort. To others, like my father, it’s a claustrophobic horror. But whether they stay or go, they will always feel the weight of home in a way I never will. My investigation of this one small town taught me that this—the birthright my parents denied me when they left Iowa–is why I’m fascinated by all such places. I will never be known the way my parents were, surrounded by people who’d watched them grow up and knew everything about their families going back five generations. Nor will I ever know anyone else as deeply or effortlessly as the people in Lovelock know one another. I desperately wish I had had that opportunity. I’m profoundly grateful I did not. And so, I will always drive slowly through small towns, feeling envy and relief in equal measure.