At the recent Left Coast Crime conference in Tucson, Arizona, an author panelist was asked how long she could keep writing stories about her early 20th-century character. Half-jokingly, the author replied that she could perhaps kill them off soon: “After all, the Titanic sunk in 1912!”

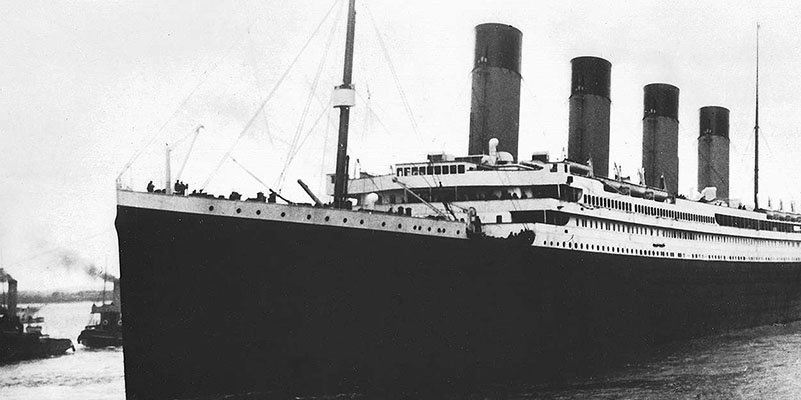

Titanic was just one of over 1,600 vessels built at the still-working Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast, in the north of Ireland, yet despite the fact it happened over a century ago, no other oceanic story still fascinates us as much as this tragedy.

Countless movies, programs, websites and documentaries have explored every conceivable aspect of the disaster, while the many hundreds of literary offerings connected to the Titanic encompass fiction and non-fiction, every genre, for every age group.

Alex Scarrow’s Candle Man combines the Titanic with other historical events, offering the tantalizing premise that, as the ship was going down, a man revealed the truth about the identity of Jack the Ripper. That was an instant purchase, at least for me, Jack the Ripper of course being the source for even more books, movies and documentaries than the doomed ocean liner.

There are numerous books about the night of April 14th/15th, with Walter Lord’s A Night To Remember still considered to be one of the most realistic accounts, while you can fill a wheelbarrow with doorstop-heavy tomes of scientific and technical accounts.

At the moment there are a number of Titanic-themed exhibitions taking place around the world too, including in Las Vegas, New York and, recently, in my own backyard of Hollywood.

Besides the movies, I wasn’t sure what connection Hollywood could have to Titanic, but it turns out one of the survivors is buried at the celebrity-filled Hollywood Forever Cemetery, just a short drive from my house. A tributary plaque to her husband, whose body was never found, is in the same mausoleum.

The Hollywood exhibit also had a picture of “professional gambler” George Brereton, a truly dedicated conman. Just hours after being rescued from a lifeboat, he had already allegedly been working another First-Class passenger/survivor by trying to involve him in a horse-racing scam.

Later, fast-talking card sharp Jean (Barabra Stanwyck) in The Lady Eve (1941) confirmed for us that cruise ships were a smorgasbord of potential crime, while today’s true crime shows often feature murder-mysteries that take place on such floating palaces.

This in turn made me wonder whether there were any real-life felons on the Titanic.

The luxury liner certainly had plenty of gold, silver, jewelry and money on board, both on wrists, necks and hairdos, as well as in wallets, purses and safes, while there were naturally rumors of more illicit cargos (and 1980 flop Raise the Titanic! even suggested it held a mysterious nuclear mineral).

Rich pickings for criminals then, and since maritime law and territorial waters are such gray areas, there seemed to be potential for another take on the famous disaster.

Alas, I should have known that this had already been fascinatingly and deeply researched on www.encyclopedia-titanica.org, among others, and that Titanic had already been used as the background to mix with fictional crime.

There was Max Allan Collins’ The Titanic Murders, and behemoth author James Patterson had gotten in on the act in one of his co-authored BookShots, Taking the Titanic, which was based around a heist onboard.

The statistics however, as they often do, proved to be rather misleading. At first glance, the Titanic seemed like it was infested with criminals of all stripes, yet the research included acts and allegations about passengers from before and after the four-day voyage.

Out of the 2,240 passengers on the Titanic, the convictions of several dozen – men and a number of women – included the more predictable thievery, drunkenness, assault and deception, but also smuggling, “prevarication”, bigamy, spying, kidnapping, preaching illegal religious ceremonies, and protesting as suffragettes.

That said, Christoher Shulver, a Titanic fireman (boiler room worker) who survived the sinking, was a thief with a long record. No wonder he had signed up as “J. Dilley.”

Another fireman, George McGough, who also survived, had been convicted of murder in Brazil in 1900. During a fight, he pushed shipmate John Dwyer into an open hold. Dwyer fell 20 feet and bled to death from his injuries, and McGough was subsequently sentenced to 15 months for manslaughter back in England.

More notably, Robert Hichens, the quartermaster who was actually at the helm of the Titanic when he tried – unsuccessfully – not to hit the fatal iceberg, served four years for attempted murder later in 1933. After drinking heavily, he had gone to see a man he thought had swindled him in the sale of – believe it or not – a small charter boat. When they began arguing, Hichens pulled out a pistol and opened fire.

As for Brereton, it’s possible his post-Titanic idea may have made it to the racetrack, but in Ohio in early 1915 his luck ran out when he was fined and sentenced to two years in prison for his part in a horse racing scam.

Unbelievably, one of his four accomplices, who was also fined and jailed, was Harry H. Homer, a career scammer – and fellow survivor of Titanic. Did they meet in the aftermath and cook up the scheme together?

By 1923 Brereton was living in California and continuing his nefarious ways, again being arrested in 1933 at, of all places, Yosemite National Park, in relation to another false horse-racing deal worth some $27,000 (over $610,000 today). He committed suicide in 1942, some 20 years after his first wife – distraught over the death of their son – had done the same.

Good or bad, every victim and survivor is listed in a new exhibit at the Titanic Belfast museum, whose silver, star-shaped building sits at the head of the slipways where the Titanic and many others were launched.

There are rare artifacts in the museum as well, including a deckchair and a lifejacket from Titanic, and the million-dollar (auction value) violin belonging to bandleader Wallace Hartley. He and his seven fellow musicians famously kept performing while the ship slid under the waves, and their stories were told in Steve Turner’s And The Band Played On.

As we approach the 111th anniversary, the real facts are that over 1,500 people died in the disaster, just like in many other events in history whose repercussions are still felt today. It’s something to remember next time you watch a YouTube video or open the latest Titanic book.