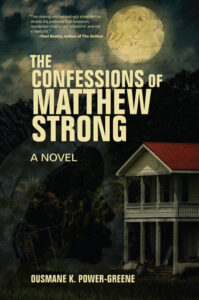

When I finished my debut novel, The Confessions of Matthew Strong, I planned a trip to Birmingham, Alabama to search for the plantation homes and graveyards of the southern slaveholders who inspired the book. Yet, when my wife suggested I bring my 14-year-old daughter with me, I hesitated. After all these years, the racist violence in the deep South that tormented me and drove my family to migrate from Alabama to New York City still haunted me. But, come on, I thought. Did I really think she or I would become targets of some white supremacist? That was ridiculous. I knew Birmingham had done tremendous work to repair the racial divide since the 1960s. The city was over 50 percent black, and statues and memorials that honored the activism of youth who responded to Martin Luther King Jr’s call for a “Children’s Crusade” dotted the urban landscape. Not to mention, the four girls- three of whom were 14 like my daughter –who were murdered when Klansmen bombed the 16th street Baptist Church in 1963 had forever changed how whites felt about the use of violence to maintain segregation. Some believe the Klan’s violence backfired after white people across the South denounced it. But, still, the legacy of racist violence—from Birmingham to Greensboro, NC in the 1970s to Charleston, SC in 2015 and Buffalo, NY this past June—make me feel on edge visiting any new city—especially those with a legacy of racist violence like Birmingham.

However, Birmingham wasn’t the city in the deep South that first became associated in my mind with racial terror. That was Atlanta. I was 8 years old when the possibility that someone might kill me because I was black first entered my consciousness. This happened after I overheard the TV news describe a string of black children in Atlanta, Georgia who some believed had been murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. What became known as the “Atlanta Child murders of the 1980s” terrorized black people all across the nation, particularly because some theorized the Klan did this to ignite a race war. Although police arrested a black man, they found responsible for at least two of the murders, this notion—a white supremacist plot to ignite a race war—continued to animate conversations in the black community up until 2019 when the police finally reopened the case.

Actually, ever since Wayne Williams was convicted of killing two of the children, black parents had clamored for the police to continue investigating the other deaths. But, once the killings stopped after Williams was incarcerated, the public-will to keep searching for more answers diminished. Only a few parents and their allies refused to abandoned their campaign for justice. Nearly forty years later, some in the black community of Atlanta responded to the police announcement they would reopen the case with, “It’s about damn time.”

When I decided to fly into Atlanta rather than Birmingham, I didn’t mention any of this to my daughter. I mean, why would I? She already knew our primary objective was to search for several plantation homes and the place where the most-wealthy slaveholder in Jefferson County was buried. I had no intention of passing this fear of travelling in the deep South to another generation. Besides, a boy who she now called her “boyfriend” was in Atlanta visiting his father. Although I suspect that her desire to join me on my search for the dead slaveholders who inspired my novel was really motivated by the faint chance we might meet her boyfriend for breakfast, she never said as much to me. In fact, she only mentioned it as a possibility and was, perhaps, as anxious about meeting his father as she was excited to spend a morning with her boyfriend.

Our plan was to rent a car at the airport and drive two hours and 15 minutes to Birmingham. It seemed fairly straightforward, and Route 20 actually went directly between the cities. We had five days—two days traveling and three days in Birmingham. Between our sojourns to plantation homes, graveyards and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, we planned to check out the World Games, an international sports event that featured alternative sports, like canoe water polo and six on six women’s lacrosse. Like me, my daughter loved playing lacrosse and the idea of watching the women’s national team play in Birmingham during our trip seemed too good to pass up.

The flight was fine, rent-a-car line, short, and our drive from Atlanta to Birmingham provided us just enough time to plan out where we’d go for the mini-documentary I asked her to help me shoot. Yet, when I crossed the border into Alabama, passing small cities only those who know the history of the civil rights movement, such as Anniston, would recognize as notorious sites of white racist violence, I felt a sense of unease. But I held my tongue, and spared her another lecture about this history that might only terrify her. Not to mention, I needed to save what she described as “boring” history lectures for when we arrived in Birmingham.

The real reason I didn’t bring up my fear of Atlanta was because I continued to be haunted by these murders. Even since my college days, I read books about the Atlanta child murders that reignited my childhood fear. Some of the most celebrated black authors, such as James Baldwin, Toni Cade Bambara, and Tayari Jones, also found the murders so traumatizing that they devoted their literary prowess to rendering this real-life horror story to the page. Reading James Baldwin’s The Evidence of Things Unseen, an extended essay about the Atlanta child murders in the early 1980s, was one of the most hair-raising experiences of my life. I was home from college when I came upon Baldwin’s book on my father’s office bookshelf. A master essayist, Baldwin’s probing intellect, his ear for southern dialect, and acute sense of how to capture the distinct way black people carried themselves within this context had brought these black mothers and fathers, some from of the poorest neighborhoods in Atlanta to life. Unlike the victim narratives within the mainstream media, Baldwin’s poignant portraits of families torn apart by this act of inhumanity captured their indominable faith that one day their children would turn up.

In a way, Baldwin’s book led to my fascination with crime writing, a genre few associate with the author of If Beale Street Could Speak, or, The Fire Next Time. And what Baldwin had captured in his essay, Toni Cade Bambara and Tayari Jones accomplished in their novels. Bambara’s These Bones are Not My Child, published posthumously, was so haunting I could only read portions of it at a time before putting it down. Jones’ Leaving Atlanta forced me to imagine the ways these horrific acts divided the black community as the scope of this crime began to come to light. While these books inspired my own novel about white supremacist crimes and black resistance, they also cultivated a greater fear of traveling to the deep South—particularly Alabama, where my grandmother was born but left under horrifying circumstances.

According to family lore, a white man who owned the land near where my great-grandfather lived nearly lynched him after a dispute. Growing up, I was never told about this incident. In fact, I first learned of it when I was visiting my own grandfather during the last days of his battle with cancer. That’s when he told me—virtually on his deathbed—about the incident, including a description of how a few white men bound my great-grandfather’s hands behind his back, dropped a rope around his neck, and pulled him up. As he kicked and fought, the son of the white man pleaded for his dad to cut him down. This, apparently, saved my grandfather from suffering the fate of so many other black men for the past century. Soon after, my great-grandfather fled with my grandmother and her sisters to New York City and never returned to Alabama again.

Why had my grandfather waited until I was in my twenties to tell me this story? Moreover, why didn’t my grandmother—who passed away a few years prior to this—ever tell me this story herself? I often wondered if both of them did not want me to carry the weight of this history to my deathbed, as my grandfather had done.

On drive to Alabama, I couldn’t decide whether or not I should tell my daughter all of this. I wondered if denying her this horrifying story I somehow prevent something like this from happening again. Perhaps, to me? Looking back, I wish I had asked my grandfather all these questions. Instead, I just listened and nodded along as he told the story.

In many ways, I have come to view my decision to bring my daughter to Alabama as an act of defiance. I no longer intended to allow my fear of this history and family legacy dictate the choices I made. Over the past few years, I brought her with me to marches and demonstrations—especially after George Floyd’s murder—even though I instinctively feared some police officer or angry onlooker would target me or my daughter. Like many black pre-teens, she was inspired by the Black Lives Matter to speak the unspoken and challenge what has stood unchanged for decades. Within this context, she learned on social media sites and through conversations with other students in the black student group at school about how monuments and memorials celebrated enslavement and other systems of racist violence. Openly defying historic markers in public spaces has come to represent one of the most important elements of the Black Lives Matter movement, and young people like my daughter were at the forefront of these efforts. After all, it was a young person who wrote the letter to the Charlottesville city council that set off a movement to remove the statue, which inspired white supremacists to hold a counter-demonstration and led to the murder of an anti-racist activist.

Birmingham, too, had its own reckoning with Confederate monuments in Linn Park, which forced the city, then the state, to reconsider under what circumstances monuments and memorials should be removed. Ultimately the governor signed into law the Heritage Preservation Act to prevent city and local municipalities from taking down historic monuments—an ironic imposition of outsider political interference from a state that once prided itself on “state’s rights.” When a judge overturned this law, the Alabama Supreme Court countered that decision with a ruling in favor of the state—all of which illustrates how red-hot this fight over the legacy of those who took up arms against the federal government remains to this day. Perhaps as disturbing was the news that city officials in Alabama refused to fire a police officer affiliated with a white supremacist organization based on the claim that the employee was entitled to his or her “beliefs.” Only after activists brought this to the attention of the national media did the city reverse its position.

Even if my daughter knew nothing about this specific case, or politicians in Alabama with white supremacists affiliations, on January 6, 2020 she watched off-duty police officers and military personnel don Confederate flags and neo-fascist symbols in their effort to overthrow the government. With all this swirling in my mind as we drove to Birmingham, I decided not to pass on the fear I’ve carried all my life about driving around in deep-South states like Alabama—and visiting cities, such as Atlanta.

The trip went well. We visited a renovated plantation home and had her shoot me walking the grounds and discussing the history of slaveholding in Jefferson County for a documentary to accompany my forthcoming book. We even tracked down the cemetery where the slaveholders I studied had been laid to rest. Of course, this did freak my daughter out a bit. Yet, I appreciated her willingness to play videographer, as I bent over to read the names and dates on the headstones. The conversations we had driving the back roads of Alabama reminded me how important it is that I don’t allow my fear to prevent me from having the kinds of difficult conversations necessary to teach her about our family’s past and why my family left Alabama for New York. She’s 14, after all. I can’t allow my discomfort to prevent me from telling her the truth.

***