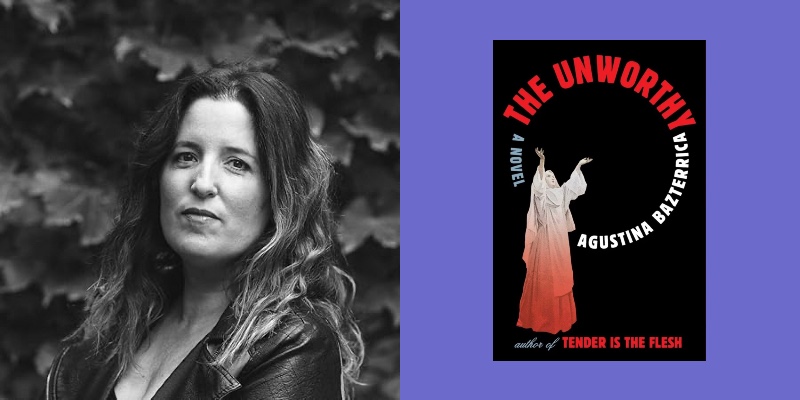

In Argentine writer Agustina Bazterrica’s Tender is the Flesh—a 2017 dystopian novel that won a major award in her country—“mass hysteria” ensues when a deadly virus seems to leap from animals to humans. In its broad strokes, the story presaged the spread of Covid in 2020. Her latest, a character-driven horror novel, envisions a different sort of catastrophe, one brought about by capitalism’s excesses.

Beautifully translated by Sarah Moses, The Unworthy takes place at a once-legit monastery that’s become a misogynist nightmare. The women living there arrive willingly—they’ve fled from environmental disasters and widespread lawlessness—but once inside, they’re tortured, isolated, brainwashed, and forbidden from speaking or reading. Bazterrica’s unnamed narrator risks death to share her story, sometimes using her blood as ink, and hiding her manuscript under the floorboards in her cell. Despite the unrelenting cruelty, the protagonist claims moments of freedom, finding reasons to be hopeful.

From her home in Buenos Aires, Bazterrica discussed the pernicious influence of political lies, art’s power to shape behavior, and the enthusiastic audiences she’s found in academia and high schools.

Tender is the Flesh was published in English in 2020. There’s a big question in the story: Is the virus real or an excuse for the government kill off its enemies?

Yes, you have that ambivalence, and readers have to decide if the virus is real or not.

In that book and your new one, your characters are living in worlds where big lies are repeated, gaining immense power. Is this a theme you set out to tackle, or is it one that developed as you come to know your characters?

When I have an idea, I need to find the elements before writing, the elements of how I’m going to tell the story. That can take months or years. It’s the most difficult thing. There’s a phrase attributed to Flaubert, the author of Madame Bovary: “With my burned hand, I write about the nature of fire.” I write with my burned body about capitalism, about patriarchy. Although I’m a person with a lot of resources and privilege, I’m not indifferent to what is happening in the world. As we are speaking now, women are being raped and killed. So I’m always trying to understand why we live in such a violent world.

Does dystopian fiction enable you to do that in ways that other kinds of fiction might not?

It’s not that I’m an expert on dystopias or horror fiction. I don’t believe in genres in the sense that I think everything is literature. I read a lot of poetry, a lot of essays. After Tender is the Flesh won a big prize here in Argentina, I was asked in an interview: What genre is your novel? I thought, OK, it’s a dystopia. But when I was writing I wasn’t thinking: I want to write a dystopia. I wanted to write this story. I like to think about things that are latent now and take them to the extreme. Today with climate change we are seeing the consequences, but in The Unworthy I take those consequences to the extreme.

The narrator of The Unworthy almost invites us to think that she’s violent or sadistic. She explains how she sews cockroaches into another woman’s pillow, hoping they’ll crawl into her ears and eat her brain. Do you make a concerted effort to balance the good and the bad in your protagonists?

I’m not interested in fiction where the characters are without nuances, because I don’t think that is real at all. When I start writing, I’m living with the characters. When I’m washing the dishes, maybe I can see what is happening with my character in a scene I haven’t written yet. I watch them, and I have to write what they’re doing. They are alive in my mind, and if they are alive, they have to have nuances.

One of the inspirations for this book was my own life. I went to a Catholic school here. The nuns told us that we have to love each other as Jesus said. And then the reality was really different. We were really mean to each other, the opposite of what Jesus said.

As the book goes on, your narrator finds reasons for joy. Is this a hopeful book despite all of the horrible things that happen?

I do think that it’s a book about love. But the word “love” is never written. Of course, I don’t believe in religions—if you read the book, you can take that conclusion. But I do believe that there is—you can call it God, Goddess, whatever you want to call it—an energy that creates everything. So what I try to work toward in the book is this: Where is God, really? The God that they pray to? Or is God in the links she has with Lucía and Circe (a human character and a cat)? I think that when you have relationships of love and empathy with others, you are connecting with God.

In your books, humans have completely destroyed nature. Can art shape behavior in a way that could, say, begin to repair the environment?

Yes, I do think that it can shape behavior, because when you read and when you are connected to art, you have the possibility of dialogue with people that worked and lived 200 years ago, or people that are living other realities. Your own reality expands, and you start looking at it in a different way. I know people who were saved by literature, people without resources, without formal education—literature did that, it saved them. Art and literature are really powerful. That is why in dictatorships—here in Argentina, we had a dictatorship—they prohibit books because they’re really powerful.

Academic studies have been written about your work—the way it critiques capitalism, meat production, sexism. Have you read any of these?

No, but I had some interviews with people who are writing doctorate works. A few weeks ago, a student from the United States interviewed me. And also here in Argentina, I am teaching Tender is the Flesh in schools. I’ve talked to 100 schools, from 2018 till last year.

Wow, that’s great. These are groups of teenagers?

Yeah, 16, more or less. In my Instagram, sometimes I post my visits to school. The students film book trailers as the characters of the novel, they write poems, they write songs. It’s incredible.