Sarah Weinman’s latest book, Scoundrel: The True Story of the Murderer Who Charmed His Way to Fame and Freedom, now out in paperback, tells the story of Edgar Smith, who in 1957 killed 15-year-old Victoria Zielinski and was sentenced to death for it. From death row in New Jersey, Smith maintained his innocence, eventually winning the attention of renowned conservative William F. Buckley. Smith convinced both Buckley and Knopf editor Sophie Wilkins—through whom he published a book about his “wrongful” conviction—to help him win his freedom.

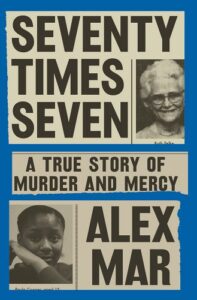

Alex Mar’s new book, Seventy Times Seven: A True Story of Murder and Mercy, out this week, tells the story of a 1985 murder in Gary, Indiana, committed by 15-year-old Paula Cooper. Despite her age, Paula was then sentenced to death for the crime. A few months later, her victim’s grandson, Bill Pelke, decided to publicly forgive Paula and campaign to spare her life—and the story exploded in scope from there, stretching from the steel mills of Indiana to the halls of the Vatican.

Weinman and Mar recently sat down to talk about finding the stories at the heart of each of their books, how our criminal justice system is built around storytelling, and the slippery definition of “justice.”

Mar: So let’s talk about Edgar Smith. He’s been received as a controversial character, and he’s definitely unsettling in many ways.

Weinman: Well, it’s not a book about Edgar Smith.

Mar: Right.

Weinman: I think if it had been, then that would’ve just been the story of a killer, and it would’ve felt like I’m just letting him run the table with pronouncements and lies and sophistication and take up too much oxygen in the narrative. And, as I’ve said before, to me he’s the least interesting person. He’s just the sort of the lodestar around which far more interesting people revolve—for the purposes of this story.

Mar: I wanted to talk about what Smith represented for William F. Buckley, and what perhaps Buckley was eager for him to represent. You’ve got this tough-on-crime conservative who then discovers this man on death row who claims to be a great fan of National Review—

Weinman: Except, as we later learn, that was all a lie.

Mar: Yes—which is hilarious. You know, there’s a convenience to being able to demonstrate that, “as a mega-conservative who’s taken this hardline stance, I do occasionally think in a more open-minded fashion about the justice system.” But he’s extending himself to someone about whom I have to believe he thought, “Okay, it wouldn’t be that hard to insert him into my social circle in a way that gives me cachet.” So here’s the question: To what extent do any of us give the benefit of the doubt to people who we feel look and sound like us? To people we can picture inserting into our own social circle without effort? And then how much does that inflect how the justice system works—or is played?

Weinman: I am sure that it has a tremendous effect on how the justice system plays out. Because humans are social creatures. And so people help like-minded people or people they aspire to be friends with a little more readily than people who are not like them. And, you know, speaking for Buckley, it makes perfect sense that he would gravitate to someone like Edgar Smith who displayed literary talent. And some of his mentorship of young men got a little weird, especially if you read Ross Douthat’s book, which was excerpted in The Atlantic, where he talks about skinny-dipping with Buckley. Or Alex Chee’s amazing essay about being a cater waiter for the Buckleys. I also think, between him and Edgar, there was an element of a Pygmalion, male-Galatea thing happening.

But to me, the book became the book the moment I learned about Sophie Wilkins, who was Smith’s editor at Knopf. I really, truly thought, “I’m just going to look at correspondence between an editor and her author.” I didn’t think it was going to be anything more than professional stuff. And then it became a huge deal. As soon as I started reading Sophie’s letters—and particularly the letters that I think of as NC-17-level, between her and Edgar—I was like, “Oh, this is the book!” [Smith and Wilkins’s correspondence quickly became openly flirtatious and sexual.] Because I felt like I intuitively understood Sophie as a person in a way that I was never going to fully understand Edgar. Once I realized that Sophie was such a pivotal character, and that it was really a triangle, then the book made so much more intuitive sense to me.

Mar: Related to that: Edgar Smith ends up not being a participant in the book. And unlike in a lot of situations, that was the writer’s decision, as opposed to the subject’s. And I think I understand personally why you made that decision, but I was curious to ask you more about it.

Weinman: I had done enough research and reporting even by the time I reached out to Edgar, a few months into the process. I had already seen about half a dozen versions of why he killed Vickie—because every time he would appear before the parole board, they would ask him, and he kept giving all sorts of answers. And ultimately the one I landed on, which I did include in the book, is what he said in his last hearing. And his answer then was, “I was angry.” And I thought, “You know what? I don’t think it’s really much more than that.”

Mar: So getting his perspective was less important to you.

I loved—to the point where ultimately I think it may even be my favorite part of the book—the coda to Scoundrel. You make this choice to end the book by jumping back in time to the very first young woman who reports Smith—

Weinman: She wasn’t even a young woman. She was just about to turn 10.

Mar: It’s just gross. And he experienced very minimal consequences for that assault. And there’s this feeling of deep regret that I think most readers must feel when they read that section at the end and they realize that any time girls and women are not listened to by the authorities, a much larger chain of events is possibly being set into motion.

Weinman: And in the quest to elevate Edgar’s literary talent, Buckley and Sophie Wilkins forgot that he caused severe harm, murdering one girl, sexually assaulting a younger girl, and abusing his wives. And maybe some of this could have been prevented. It’s hard to know.

I just didn’t want people to think that there was doubt about Edgar. I was really trying not to structure Scoundrel as a whodunnit. That’s why I wrote the introduction in the way that I did: you start with him dying, and he’s in prison, and how did he get there and how the hell did this happen? And what were the forces and who were the people involved in creating what I view as a tragedy?

Mar: I also made clear in my prologue that Paula Cooper’s case is not a story of wrongful conviction. And with that case, I think, a huge moral challenge for the reader is to accept that this young girl did commit this truly horrific crime—and knowing that, what would they have chosen as her punishment? Where do their sympathies lie? And do those sympathies shift as they continue to read? Does their idea of justice in this scenario evolve as they work their way through the book?

Something that I thought about a lot while writing this is the degree to which our justice system responds to storytelling. Right? I mean, as a writer I thought about it that way—but I think actually, quite literally, that’s an important piece of the system. If you have an opening to tell a more convincing, more fully fleshed-out story of someone like Vickie within the justice system, then potentially there’s a different outcome. But if you have a powerful public figure getting behind an innocence narrative for someone who’s been convicted of her murder, that can push the outcome in another direction, right? And that version of the narrative of her death, in this case, involved a diminishment of her as a human being. And for Paula Cooper, her appellate team coming up with a richer story about her background—her chaotic, abusive childhood—and making sure the press knew about it both here and across Europe, that really informed the public’s awareness of her situation.

Weinman: And the fact that her story reached the Vatican! I mean, it became so much bigger than Gary, Indiana.

But to your point about storytelling: what is a trial? A trial is two adversarial versions of a story. It’s the prosecutor’s job to tell their story about what happened and make the evidence fit their narrative. It’s a defense lawyer’s job to refute that and either come up with their own narrative or just be constantly at odds with what the prosecution is saying. The witnesses tell their story in a very prescribed way. The judge is even telling a story, shaping what evidence gets let in or left out. You have closing arguments where you reiterate or even fashion a different narrative. And then the jury is processing these competing stories the entire time.

Mar: Related to this question of how a narrative about justice is built in our system: you have Paula and her sister and her grandfather, on the one side—because the rest of Paula’s family really abandoned her—and you have the victim Ruth Pelke’s family on the other. The whole justice system is designed to keep families on either side of a crime apart. And it’s not really spoken about that much. The idea that the two families might have anything in common as human beings—

Weinman: —is just anathema to how things are supposed to function.

Mar: Anathema, that is the word. And any reaching across the aisle is also highly likely to complicate the prosecutor’s agenda.

Weinman: And so the families banding together complicates a narrative that is supposed to be kind of binary.

Mar: Exactly.

Weinman: Which is this idea of the defendant as mastermind, the defendant as villain, the defendant as perpetrator—when in fact, you know, masterminds and villains are for fiction and TV, and perpetrators are often victims.

Mar: Yes. And it allows the prosecutor to keep everyone’s relationship to the sentence deceptively simple, right? The family of the victim isn’t thinking about the potential victimization of the family members of the defendant.

You said that you feel good about the fact that Edgar Smith was not ultimately executed. Well, you’ve written about these various women he touched, whose lives were entwined with his. Whether or not they continued to love him or trust him, his execution would’ve had a horrible impact on them.

Weinman: I’m sure. A year after he was convicted, he did get within half an hour of being executed, and I think of what that would that have done to Patricia—his first wife, who was still married to him and stuck by him, at least through the early sixties. And their daughter Patty Ann. There’s already going to be trauma, so why are we making it worse?

This whole “eye for an eye” thing is just not where I’ve ever been at. It doesn’t solve the problem pro-death-penalty people think it solves. I’m curious what you think about this: I hate the word closure, because I think once you have experienced significant violence in your life, or you’ve had a family member murdered, there’s no closure.

Mar: It’s so interesting you bring up that word. Because, as you know, Paula’s victim’s grandson, Bill Pelke, ends up discovering, little by little, a string of individuals who are also murder victims’ family members who chose not to support the death penalty in their cases. It’s like finding other unicorns! And eventually they become this extraordinary collective of people who are able to understand each other. And I got to know several people in that community along the way. And it was deeply fascinating to talk with them honestly about their response to the murder in their family. Across the board, they had all been furious, traumatized. And for most of them, the fact of trying to live with their anger, to pursue the course of all-out retribution that was suggested by the prosecutor—it devastated them further. And they’re very clear about that. A number of them started drinking, using drugs, couldn’t hold a job, stopped talking to their friends—because they were consumed by anger. And so when each of them chose to forgive, it was—you know, for a certain number of them, part of that was driven by faith, right? But it was also a means of survival.

So, bringing it back to this idea of closure: Most of these individuals I got to know, they said they were completely insulted by the idea that taking someone else’s life was somehow going to bring back the balance of things. “Your family member is dead, and now we’re going to kill this guy, and somehow we’re all good now.” They found it insulting—that was the word I heard.

On a different note: it’s kind of interesting to think about how both of our books are driven in part by correspondence. The letters in our books serve as a window into the psyche of these very important players, and really significant gaps would exist in the narrative without that. Edgar Smith was on death row, Paul Cooper was on death row, and their way of communicating with the outside was primarily through letter-writing. There’s an incredible, essential importance to correspondence for those who are incarcerated.

Weinman: And that’s why the middle section of Scoundrel had to be so letter-driven, because if you’re Edgar and you’re on death row, you get, if you’re lucky, about one hour a day to be outside. So what does that do to your mind? And if your only avenue of communication with people is by letter, you kind of alight on that—like you’re a drowning man, because you kind of are. It absolutely makes sense that Edgar, if strange women were writing him, would have no sense of boundaries. And it would take maybe two letters for him to start getting mildly inappropriate, and then it would just go off the rails really quickly. But in fairness, Sophie met him and, you know, developed her own fantasy.

Mar: In what was supposed to have been a professional relationship.

So when Bill Pelke decided to forgive Paula, he looked up her address at the Indiana Women’s Prison and wrote to her on death row: a 40-year-old man writing to the teenage girl who had killed his grandmother. And that was the beginning of hundreds, even thousands, of letters over many years. And one of the many things that I found fascinating in their correspondence was that it didn’t always have the power balance you’d assume. When you have this girl on death row, you assume that she’s so grateful to hear from anyone, especially her victim’s family member who’s forgiven her. But the reality was that, at times, Bill seemed to need her more than she needed him. That was a revelation to me.

Weinman: Right. It’s almost a transference thing happening.

Mar: Very possibly. Because he was going through a really difficult period in his personal life—particularly his relationship with Judy, who later became his wife. He felt that he had received so much judgment from his friends and family about that relationship, and he didn’t want to hear the same old thing over and over, like “You need to leave that woman.” So who’s the perfect person to confess to but this girl on death row, who is the perfect captive audience, literally? But he’s also writing into this mysterious void. He doesn’t know her, but she’s there and she’s ready to receive his letter and write back a thoughtful response, over and over. Multiple times, he was essentially asking for life advice from a teenage girl.

Weinman: It’s pretty staggering when you spell it out that way. What does that say about Bill that he had no one else emotionally to turn to other than Paula? A teenage girl on death row—it’s like he’s asking for emotional labor from her.

Mar: I’ve thought a lot about Paula’s writing. Before the crime, she bounced around—I think she went to ten different schools by the time she was arrested, which is a lot. And she barely went to class during her last few years outside. And yet when she’s on death row, because of all this letter-writing, she develops a voice, and you can actually see her vocabulary, her mode of self-expression, her style, just develop. Because, for a stretch of a few years, she was writing letters all day, nonstop. And I have no doubt, reading her letters to a whole range of individuals, that she understood that she represented different things to different people. You’ve got Bill, who’s tied to her by the crime—that’s a very specific relationship. But then you have, for instance, a friar in Rome writing to her about how he thinks the Vatican can get behind her case. Well, she’s very careful with her language with him and with other representatives of the Catholic Church. And then you have members of the press where sometimes she’s so fed up, she’s just sassy with them, and doesn’t fully understand what it means to be quoted in the press.

Weinman: Because she’s still an impulsive teenager!

Mar: Thinking about the whole spectrum of people whose lives intersected with Paula’s, you know, I realize that, while there’s a tragedy at the center of this story, for me writing it, it was actually very hopeful. Because there’s the cumulative effect of the life choices of this larger cast of characters. So many of the people, across the board, chose to do the unusual thing—whether it’s Bill forgiving publicly; or Monica Foster, one of Paula’s most passionate and relentless attorneys; or Earline Rogers, a public school teacher and a Gary representative who was the first person in the state to speak out after Paula’s death sentence. And over time, the story connects up with, ultimately, the end of capital punishment for juveniles in this country. So I tried to really focus on that: the bigger story that entire cast of characters could tell.

I mean, you did the work of fleshing out all of the women who collided with Edgar Smith, and that ended up being very powerful. It’s also bigger as a story, a bigger project to take on. But it’s in the work of looking at that bigger picture that maybe we can do a better job of wrapping our heads around how our justice system truly works, and how our working definition of “justice” can hurt families and communities. And maybe that’s one very small step towards a different system.