You won’t find Von Goom’s Gambit described in any chess textbook.

But here’s the history. On April 5 1997, Von Goom entered his first ever chess tournament: the Minnesota State Championship. In his initial match, he lost to a man named Curt Brasket in twenty nine moves. A series of equally humiliating defeats was to come. Von Goom lost the further six games he played, including one in three moves, and another – after 102 moves – to a five-year-old child.

He fared no better in the years that followed. Close to half a decade later, in fact, after studying relentlessly and entering numerous tournaments, Von Goom had failed to win even a single competitive game of chess.

The other players on the circuit viewed him as an eccentric and slightly pitiful man. A figure of fun. But then Von Goom discovered his Gambit: a sequence of moves that guaranteed victory, whether starting as White or Black. At that point he entered the Greater New York Open, and he began to win.

His first opponent died of a heart attack.

*****

I read about all of this ten years before it happened.

Because the character of Von Goom exists only in a short story. Von Goom’s Gambit by Victor Contoski was originally published in 1966, in Chess Review, before being reprinted a handful of times. One of those was in a slim volume of science fiction stories that somehow found its way into the reading room of my primary school.

I remember being captivated by it.

Part of that was down to the idea of the Gambit itself. Out of all the possible arrangements of pieces on a chessboard, Von Goom had chanced upon one so alien to the logic of the human mind – so abhorrent – that it could wound and kill. Following that initial heart attack, Von Goom’s opponents in the story meet various terrible fates. One breaks down in tears at the sight of the board before him. Another is violently sick. A third is driven insane, while members of the watching crowd are turned to stone.

As a ten year old – obviously – I loved this a great deal.

But even more than the conceit, what captured my imagination was the way in which the story was told: so dispassionately, from a distance, always treating the Gambit itself as something real. The reader is told of the chess textbooks in which they won’t find it, the manual in which it is warned against without being described, and – perhaps most intriguingly of all – the ones in which the Gambit is listed in the index without a page number.

I think that was the idea that kept me returning to the story. The notion that there was secret knowledge out there in the world, hidden and hard to find, but powerful if you did.

As the story itself says, you won’t find Von Goom’s Gambit described in any chess textbook. But it is still possible to read the story. The text remains available online, albeit in a very basic format on a website that will presumably only last as long as websites do. The book in which I first read it is an anthology of SF stories called Mad Scientists, which is long out of print. Physical copies still exist, but they can only ever be decreasing in number.

At some point in the future, the content of the story itself might become a kind of secret knowledge. Perhaps all that will remain is a warning – entirely detached from the fiction – never to seek it out and play it. Nobody will know how Von Goom’s opponents finally manage to counter that blasphemous Gambit of his.

I certainly won’t tell. To find out, you’ll have to search for the story.

And read it while you still can.

*****

The feeling the story conjured up in me is probably a fairly natural one at that age, when adult life seems full of mystery. But the fascination remained. Von Goom’s Gambit clearly draws heavily from Lovecraft, and I remember, a few years later, being equally entranced by the possible existence of the Necronomicon, a blasphemous and forbidden text that promises the careful (or careless) student access to unfathomable cosmic horrors.

It’s a familiar and recurring motif in fiction: the search for a work of art that may or may not exist. One that is difficult to find. One that is rare because it’s awful, and which is sought after for both reasons. The idea speaks to a human desire to face the forbidden simply because it is forbidden. To be a member of the select few that have gone through an ordeal that others have not. To be let in on a secret even if learning it will ultimately destroy you.

In John Carpenter’s Cigarette Burns (2005), a man is tasked with tracking down the last remaining copy of La Fin Absolue du Monde, a film that was destroyed after driving the crowd at its only showing into a murderous rampage. Eventually we learn its horrible content: the documented torture and mutilation of an angel, the sight of which breaks the mind of the viewer.

Nobody should ever watch such a thing.

But of course, there are people who want to.

I remember seeing The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in my early teens. The film was banned in the UK at that point, but one of my friends had managed to get hold of a scratchy VHS cassette, a copy-of-a-copy. His parents were out. There were maybe five of us there that day. We knew we weren’t allowed to watch it, and even the act of doing so felt transgressive and frightening.

But we were teenagers.

What could possibly be so dangerous about it?

Then someone turned off the lights and pressed play. And as the ominous initial narration began – that solemn and serious voice implying that the horrors we were about to watch were real – you could have heard a pin drop in the room.

*****

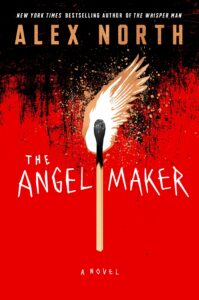

When I first started planning and writing The Angel Maker, all I really knew was that I wanted to add to this whole tradition in my own small way. The characters would be searching for a rare and forbidden text. Some of them would end up doing so for innocent reasons, of course, but there would be others who genuinely coveted the dark knowledge they imagined it contained.

An obvious first question was what might be of so much interest to a collector?

In the real world, scarcity affects value. Notoriety does too. The so-called “Wicked Bible” (which accidentally omitted the word “not” from a commandment, encouraging the reader: “thou shalt commit adultery”) was first printed in 1631. Only a small number of copies survive today, and they occasionally change hands for appropriately ungodly amounts of money.

I wanted the text in my story to be a very rare edition indeed, and I also wanted it to be tainted by genuine darkness. I settled on the journal of a fictional serial killer called Jack Lock, an item that would be valuable in and of itself to certain damaged people. But I also wanted it to contain some kind of secret knowledge, which raised further questions. What else might drive people to seek this book out? What could there possibly be, written between its covers, that might make reading it so dangerous?

A confession of some kind, perhaps?

The solution to an unsolved mystery?

Well … maybe it would be both of those things in a way. But I wanted something even worse. And in the end, I went with an idea that has haunted me more than a little for many years now, and which engages with a number of the themes that have always interested me.

Nature versus nurture.

The influence of the past on the present.

How much control any of us really have.

Life as a chess game, I suppose. The pieces moving in the ways they’re allowed to. The positions playing almost inevitably out. And then – finally – the gambit that has been lying at the heart of the story all along.

But you’ll have to read the book to find out what it is.

***