Vivian Parry, the main character of Alexis Soloski’s Here in the Dark, is a perceptive theater critic for a New York magazine. She’s tough on hammy actors, but even harder on herself. Despondent since her mother’s sudden death, Vivian is a self-proclaimed “abyss where a woman should be,” one who dulls “any genuine feeling with casual sex and serious drinking and rationed sedatives.”

When a grad student asks to interview her about the life of a working critic, Vivian reluctantly agrees. Her meeting with David Adler seems unremarkable. She’s nearly forgotten the encounter when, a couple weeks later, his fiancée phones her at work. David has disappeared, the woman tells Vivian, “and you are the last person to see him.” This pulls Vivian into an increasingly complex mystery that threatens her safety and leaves her questioning her prized skills of discernment.

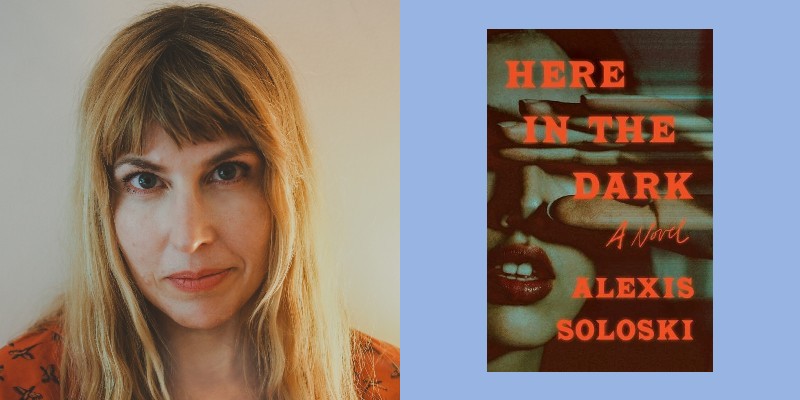

With snappy dialogue, biting humor and a gratifying, well-earned resolution, it’s an excellent debut. Soloski, a New York Times culture reporter and critic, took a few minutes recently to discuss the real-life incident that inspired her book, what people misunderstand about critics and how she’s nothing like her protagonist.

What was the spark that got you writing this book?

It’s more than a decade ago now, but when I was at the Village Voice, someone called and asked to interview me about my work. I was very flattered. I was young and female and a theater critic, and these things were not very common. They’re still not incredibly common. I did the interview, and then I was told that he was missing, and that I was the last person to have seen him. The article never appeared, and I always wondered what happened. I googled his name, but it was too common a name to really come up.

A fact about me is I’m pretty boring. Safe choices are in my DNA. I just wanted to write about someone who did not make safe choices, and who sort of ran toward the danger at every turn, someone who did not have good boundaries and a solid network of family and community. To take a little bit of the real experience and transmute it onto a character who made way more dangerous choices than I would.

When one of Vivian’s colleagues says something stupid, she wonders if “his aggressive idiocy is a ploy.” Maybe “he’s performing just as I perform. As we all perform.” Was that an important idea as you were writing—that to some degree, our relationships are performances?

I do think that we engage in—and certainly I engage in—social performance, that I am not the same person talking to you as I would be with my kids, as I am with my mom, as I might be with friends. The differences aren’t enormous because I’m a pretty sane person and a pretty happy person.

I’m pretty influenced by Freud’s idea of the psychopathology of everyday life. There’s also a great Vivian Gornick essay, it’s something like, “On the street, nobody watches; everyone performs.” (Soloski’s recollection of the quote is correct; the piece was published in the New Yorker in 1996.) Her thesis is that to live in New York, you have to engage in a certain amount of social performance.

Vivian has an encyclopedic knowledge of theater. Is that yours, the product of research for the book, or both?

This is my joke, and like all of my jokes, it comes from a place of pain: Vivian and I are very, very different, but I needed her to have good taste, so I gave her mine. I do, for better or worse, have an encyclopedic knowledge of theater. I had a really wonderful high school drama teacher, who had the gift that some great teachers do, of seeing who kids are before they know it themselves. He knew early on that I wasn’t going to be an actress, but I loved theater. He got me reading plays. When I was a junior, I think, he gave me a book of Chekhov’s five major plays.

And then when I got to Yale, I started reading my way through the shelves. A wonderful professor who’s still there, Mark Robinson, heard that there was this undergrad who was checking out every book. He gave me the reading list for the dramaturgy and dramatic criticism graduate students, and he said, I think you think you should organize your reading a little more deliberately. I followed that syllabus and then went on to do a PhD in theater at Columbia.

So as different as you and your main character are, you can identify with her path—you thought maybe you’d be an actor, but you chose criticism.

I did, but there’s no tragedy there (like the death of Vivian’s mother). There’s no trauma. There were three reasons. One, I wasn’t a very good actor. I have severe limitations, and I didn’t want to have an eating disorder for the rest of my life. Two, the things that I was going to have to do to my face and body to be competitive—I didn’t think that those were good. And three, I’m a nice middle-class kid and I just didn’t want to take the financial risk. Back then, journalism and academia, both of which I was pursuing, were reasonable career paths in a way that acting wasn’t.

For Vivian, the two hours when she’s at the theater, watching a play and taking notes, is when she’s most alive. Do feel the same excitement when the lights go down?

When the lights go down is honestly the best part. Anything could happen—this could be the greatest night of your life. And then, usually, it’s 10 minutes and I’m like, Oh, this again. And I’m fighting with my grocery list. I think of it almost as a meditative exercise. You’re fighting to keep attention, but sometimes you’re like, Wait, I do need eggs. And then you bring your attention back.

In the book, you note that Beckett and P.G. Wodehouse, among many others, wrote nasty things about theater critics. What do people get wrong about critics?

I mean, there are some real assholes, but most critics want to like things. All I want to do is like things!

I want goosebumps up and down my arms that say, OK, this is good. I want to give myself over to something. I want that feeling of absorption, of engrossment. So I’m always hopeful, I always think this could be the night. It rarely is, but when it is, there’s nothing else like it.

Your dialogue—particularly the conversations between Vivian and Justine, her closest friend—is quick and funny. Are you a note taker? When hear somebody say something on the subway or at the office, do you file it away for future use?

I don’t think I am a note taker, but yeah, I love crackle. The fancy term is stichomythia—that’s Greek for really quick back and forth dialogue, like you see in my favorite Shakespeare comedy, Much Ado About Nothing, where Beatrice and Benedick are just going at it on the page. And I think you see it in the screwball comedies of the 1920s and ‘30s, some of the noir of the ‘40s and ‘50s.

The gift that I have is that I do so many interviews with artists, with celebrities, and those interviews at some point have to be transcribed. There’s nothing better for having you realize how people talk, and all the ways that people talk around something. The trick is to edit out all the paralinguistic “ums” and “you knows” and “of courses,” just distill it down to something really crisp and sharp.

Do you read your dialogue out loud?

No one should watch me write because I do look insane. I am absolutely a mumbler. It’s one thing to read it on the page—and obviously, it’s heightened to some degree, there’s something theatrical to it—but it still has to sound plausible in the mouth.

Your book ends in a way that I really like. It was obviously important for you to have an ending that meshes with, and adds nuance to, all the developments that came before.

I think that there’s nothing that makes you want to throw a book at the wall more than a twist that seems out of character or out of step with the rest of the book. If there is going to be a twist, it has to feel authentic to what’s come before, and it has to feel earned. Because otherwise it’s just going to feel disgusting, and you’re going to wonder why you bothered in the first place.