Every American town had a weakness, and in each place where he stepped off the train, from Bakersfield to Tucson, he would softly tip off a local, letting word spread about his significance. Sometimes he went direct to the saloon and confessed his identity to a drinker on the next stool, other times announced it upon arriving at the station: a tawny stranger with a drummer’s case and a story that would circulate like a business card until city elders asked him to speak. Waiting in a hotel lobby, he might draw someone a map of the fateful battle and sign it. He seduced people with their love of Custer, who they believed had died fighting for them. Then he made his pitch.

In Oshkosh, Nebraska he arrived in time for the Garden County Fair in late September 1914, arranging to give three lectures to fairgoers in as many days. A high leaping horse performed as did the “horse with a human brain,” calculating on command. Bentley’s Wild West put on historical spectacles at the fairgrounds, but the visiting speaker known as Curley the Crow offered a stunning account, as Custer’s scout who somehow escaped death at Little Bighorn. The audience saw a thick-set older man in black braids, closing his eyes to recall that bloody afternoon and clearly fluent in unfamiliar tongues.

Even when he was not speaking, Curley kept in the public eye at the fair: reaching second place gathering up spuds in the potato race; huffing his way to first in the fat man’s quarter mile; and mingling at an evening dance. To some he explained that he was also an Indian Agent back home on the Crow Reservation in Montana. In that capacity, he knew that land would soon be sold by the government and he could offer to sell them plots for cheap. When the fair ended, he moved on to Sutherland, Nebraska, spoke again about his experiences and was even seen trying to ride a bronco, which tossed him.

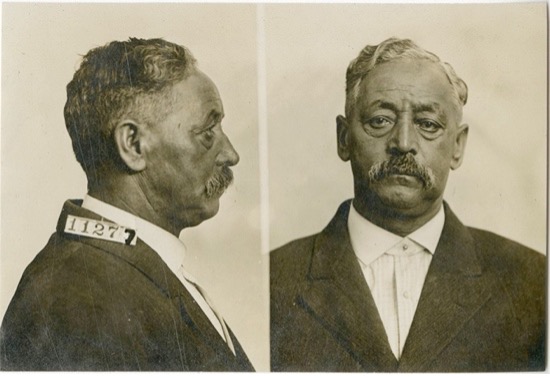

Ben McIntosh alias ‘Curley’ at Leavenworth

Ben McIntosh alias ‘Curley’ at Leavenworth

But he was back in Garden County by November, seeking out two men from Lewellen for a loan, J.C. McCoy, whom Curley had bested in the fat man’s race, and J.H. Orr, who had beaten him in the potato contest. He hoped to borrow some money until his government check arrived. The men were happy to help the loyal friend of Custer’s, who, while called “Curley the Crow,” said his legal name was actually Ben McIntosh. If they came to see him in Montana, some 400 miles away, he would repay the loan as well as treat them to a real Indian bear hunt and perhaps help them buy some ponies to take home.

The men from Lewellen were excited for their bear hunt when they set off for the Crow agency in Montana. Once there, several facts caused them to worry about the security of their loan. First, when they asked about their friend from the Garden County Fair they were directed to a man who turned out to be the actual Curley the Crow. He was not communicative or in the mood to give them money or take them hunting. In fact, he spoke almost no English, unlike their mountebank who’d captivated fairgoers for three days. Meeting the real Curley had shaken them, but the Lewellen men were further disturbed when they saw a nearby cemetery contained a tombstone for Ben McIntosh, suggesting neither of their friend’s names had been his own.

They noticed a newspaper account of a new “Curley” appearance and got him briefly held in Edgar, Nebraska, where the sheriff met his train. “Curley the Crow, now in jail,” wrote the Superior (Nebraska) Press, “has been prominent for years on the Chautauqua circuits, but has been considered for some time as an imposter by many who did not appreciate his vaunted greatness.” When the charges were somehow dropped “Curley” traveled on, reappearing to explain to the people gathered in the opera house at Elko, Nevada, “Custer was a wonderful man, but Major Reno was a coward of the worse type. Had he responded with his five companies immediately to the call which I carried to him it would have been a different story.”

He was jailed again in Illinois in December 1915, when a man from St. Louis bailed him out after McIntosh charmed him through the bars into believing he might be the genuine Curley. To prove his identity, McIntosh suggested the man buy two sleeper tickets to Montana, where he promised to lead a tour of his reservation lands and reward him out of his holdings. He lived on a battlefield, he said, and would show the St. Louis man how to make some money.

The man agreed and they dined and talked and enjoyed cigars, admiring the passing country until early one morning when McIntosh borrowed a dollar and left the train to fetch something to drink across the tracks at Edgemont, South Dakota. He let the train roll on and the St. Louis man who’d believed in him waited at the reservation. But McIntosh was by then in a fresh town thrilling a new audience with his Custer stories. All over the West, they tumbled to his con.

ii.

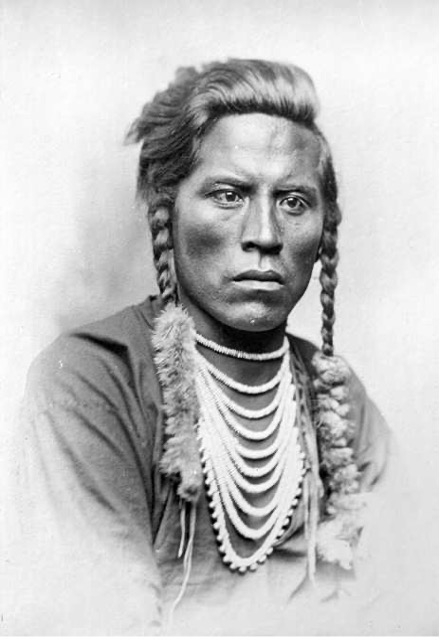

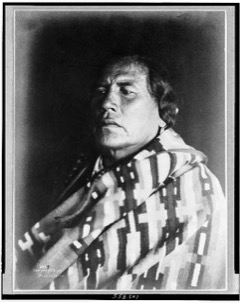

The real Curley the Crow

The real Curley the Crow

It was while searching for stories about the actual Curley that I happened on his con artist substitute, and discovered his dozens of recorded appearances around the West. It seemed surprising that Custer’s famous Scout, who was known to speak almost no English, would be wandering the country entertaining crowds in town after town, speaking at Elk Clubs and county fairs about his survival at Little Bighorn, describing how the handsome General had died in his arms. The real Curley needed permission from the government to even leave his reservation home, let alone travel about selling land as McIntosh did.

The two men did not look or sound anything alike. Had his audiences seen a picture of the genuine scout known as Curley the Crow –well-muscled and distinguished, with his own long dark hair—they might have been more suspicious of the stocky, bewigged impersonator who took their money. The man named Ashishishe (but called Curley or Bull Half Whitein English) remained one of the country’s best known Native American figures, a mountain Crow visited by photographers and battle historians.

His visitors from Lewellen, Nebraska were hardly the first to bring news of the con man using his name. The Crow Agency superintendent kept a file of the many queries received from people writing to see if they had lost their money to the genuine Curley, and he did his best to protect his reputation. “Ben McIntosh is one of the rankest frauds that the Indian business has produced in many a long day,” Superintendent Evan W. Estep wrote to a bewildered victim of the bogus Curley in Yuma, Arizona.

A speech Ben made in Chicago as Curley was carried widely enough by newspapers to outrage cavalry veterans back East, and even reached Montana friends of Curley’s. A Bronx Judge named William E. Morris had served as a corporal under Major Reno’s command during the Custer battle, and took to the New York Sun to question the wild memories of “Curley,” who sounded to him like “a public nuisance.” The story of Curley and his New York critic finally drew an answer from the Reservation Agent:

“Curly is a full blood Indian residing on this reservation, does not talk English and was not in Chicago recently. I have known Curly personally for a number of years…and according to his own statement the story as given in this clipping is untrue and was never given by the real Curly. Curly, in spite of the various stories which have been written to the contrary, does not claim that he was in the fight or took any part in the fight on Custer battlefield, but does claim he was on the field immediately preceding the fight.”

Curley was one of four surviving scouts living on the Crow agency who had worked for Custer, including Curley’s cousin White Swan, who was wounded on Reno Hill and later sold drawings of the battle to tourists. Visitors came now and then to get the men’s stories, touring the field they remembered hung with powder smoke and dust and prodding them to stir the battle’s larger controversies: Curley was said to be the last of Custer’s men to see him alive. To the end, the Crow scouts disagreed.

McIntosh was not the only one who put words in Curley’s mouth: He had let others, in newspapers he could not read, give romantic versions of his “escape” from the battle in which he had not claimed he fought – sometimes by cutting a blanket to make himself leggings in the style of the enemy or even gutting a dead pony and hiding inside its carcass until the fighting ended. In some accounts he begged Custer to escape with him, offering a second disguising blanket, but the General nobly refused.

The battle would not die in the memory of a public that embraced purported survivors, even while warriors and their families from the victors’ side recalled that event quite well. When the two met years after the fighting, the Hunkpapa chief Gall, proud to have killed soldiers that day, mocked Curley for his escapes, asking if he was a bird, “Where are your wings?” And Sitting Bull told a Montana reporter, “a rabbit could not have got away after Custer was surrounded.”

Curley gradually stopped correcting the stories that came back to him on the reservation, and occasionally echoed familiar newspaper versions. Mostly, his silence became assent. He finally lived near the grassy battlefield he had so famously escaped, which he toured on horseback each morning. “I have always told the same story,” he explained to the Custer historian Walter Camp, “but there have been different interpreters.”

iii.

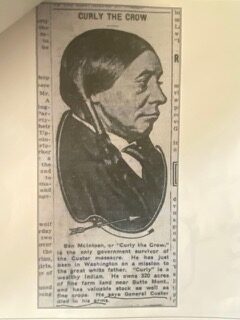

Ben as Curley out West

Ben as Curley out West

Ben McIntosh’s first recorded appearance as Curley seems to have been 1908, when he stunned the people of Ogden, Utah with his Thomas Berger-like origins tale:

“When five years old, while riding a pony near where he was born, twenty-one miles east of the Yellowstone Park, he was carried away by Mountain Cheyennes. Later he was captured by the Comanches and then the Apaches, so that when he was 23 years old he found himself in northern Texas, unable to tell anything as to his parentage except what he remembered as a child. At the head of a band of Apaches he made seven Cheyennes prisoners and was about to put them to death when one of them recognized him and, as immunity from harm, told of carrying him from home when a child and he offered to guide him back to his parents.” (The Weekly Sun)

McIntosh was a practiced actor by the time he arrived at Topeka’s Union Pacific depot on April 28, 1916, and checked into the big Hotel Throop, known for its $2 dinner dances. On his second night he took a pistol from his case and fired a single shot, disturbing the guests heading toward the lobby for dinner. The noise also drew police and a city reporter, who found a gray-haired older man in his room, smoking a pipe and wearing a three-piece suit. The gun beside him had gone off accidentally because of its hair trigger, he told them, gravely adding he was Curley the Crow, “sole survivor of Custer’s last stand.” The city reporter was thrilled to meet a man of history, and news traveled the town of the visitor who had watched Custer fight to the end.

Soon after firing the gunshot in his hotel “Curley” came to the attention of the Kansas Historical Society, which arranged a hero’s welcome. He was put at the head of Topeka’s town parade, wearing a wide-brim hat, and given the chance to speak at the Y.M.C.A. about his vivid life.

Curley portrait made by Boeger’s studio, Topeka, 1916. His “survivor” badge even has the battle’s wrong date, June 26, 1876

Curley portrait made by Boeger’s studio, Topeka, 1916. His “survivor” badge even has the battle’s wrong date, June 26, 1876

Someone at the Historical Society loaned him a Native war costume from its collection to make him more comfortable. (Even when he appeared in towns wearing a civilian suit and without his braided wig people liked to dress him up to complete their fantasy.) But the secretary of the Historical Society, an adopted Wyandot himself named William E. Connolly, later claimed to have found McIntosh unconvincing upon meeting at the Y.M.C.A. If he did spot him for a fake, he did not make his suspicions public until “Curley” was gone.

He was taken to Boeger’s photography studio to have a portrait made for hanging. In it, he is bareheaded and without braids and wears a suit and tie, his “official” government survivor badge pinned to his lapel. He spoke at the Topeka high school, dined at the Sheriff’s home, and addressed his brother Free Masons, for a $25 fee. McIntosh, alias “Curley,” next solicited his new Topekan friends, explaining he was also there in his capacity as an Indian land agent. The government would soon be opening the Crow reservation to homesteading, he said, and he could offer them his 29-section ranch at a fair price ($4 an acre), rather than sell at whatever amount the government set. Being an Indian, he was unable to purchase it himself but promised he could buy it back in his other capacity as president of the Yellowstone National Bank of Billings, Wyoming.

Hotel Throop, Topeka

Hotel Throop, Topeka

“It won’t cost you a cent and you’ll make big money,” people remembered him saying. “All you have to do is file.” One of his investors had sent bouquets during his weeks at the Hotel Throop to brighten the place for a promised visit by Curley’s daughter. When he finally slipped out of Topeka on the evening train, taking over $1000 in deposits, Ben left behind a roomful of flowers. Topeka’s chief of police soon received a letter from his counterpart in Albuquerque, warning that ‘Curley’ had pulled off similar swindles in New Mexico: “When he is drunk, he talks considerably, is quarrelsome and usually tells people that he is the sole survivor of the Custer massacre.”

As Ben told it, his father was a Scot who had led Brigham Young to the Great Salt Lake, his mother a Canadian Sioux (not Crow) and Carlisle student who was sometimes Sitting Bull’s sister, other times Red Cloud’s. Her relation to these chiefs had shielded her son during the crucial battle, and being abducted often as a youth had given him a wide knowledge of tribal languages.

McIntosh’s tales resembled frontier potboilers that might have sold well as books instead of preambles to his scams. In fact, he contracted with an Illinois woman named Mabel Sturtevant to publish “Curley’s” autobiography, and visited Sturtevant in Chicago to dictate the Crow’s story. During these editorial sessions their collaboration became intimate. Sturtevant was already under investigation for abusing the mails in a separate scheme, and a visiting post office inspector reported, “I saw the Indian frequently in her office.” When a college student living in her home came in unannounced, she saw Ben kissing Sturtevant without his dark wig, though apparently in bronze makeup. McIntosh fled town with his hotel bill unpaid.

iv.

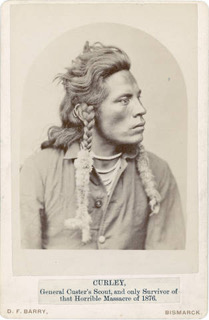

The true Curley in Bismarck, 1876

The true Curley in Bismarck, 1876

McIntosh was not the only one who put words in the real Curley’s mouth: A lot of blank space was left for journalists to fill in between the point where Curley rode away from Custer on the afternoon of June “5th 1876 and the later discovery of the battle’s dead by Lt. James Bradley, chief of scouts for the 7th Infantry under Gen. Gibbon.

“I joined Custer so that I might hold our land against our enemies, the Sioux and Cheyennes,” recalled the Crow White-Man-Runs-Him. In the early hours before the battle, three Crow scouts had looked down over the Little Bighorn Valley and spotted a “tremendous village” on the river about fifteen miles off, calculating its rough size from the clouds of dust raised by the villagers’ ponies. (It would turn out to be at least 5000 villagers, including roughly 1800 warriors).

Later in the day, Custer famously divided his force into a battalion each for himself, Major Reno, and Captain Benteen. Mitch Boyer, Custer’s guide who interpreted for the Crows, thanked and dismissed the scouts, their job completed, then stayed to share the fate of his commander, as Curley recalled:

“Mitch said that Custer told him the command would very likely all be wiped out and he (Custer) wanted the scouts to get out if they could. I was riding my own horse. I found a dead Sioux and exchanged my Winchester for a Sharps rifle and belt of cartridges. On my saddle I had a coat made of a blanket with holes cut out for arms, and a hood over my head. In this fashion I rode out.”

News from the fighting had still not yet reached the outside world almost two days after Custer’s death, as the flatbottom steamer Far West sat at the mouth of the Little Bighorn River, tethered to a cottonwood on an island in the center of the stream. Early that morning of June 27th, its crew were waiting for word about the actions in the valley some miles away, where they had seen smoke for two days; the sky was now clear when the willows along the bank parted to reveal a young rider on a weary Indian pony. The steamer’s crew remembered him carrying a blanket and wearing a breech-clout, his carbine held above his head to signal his good intentions. He was probably 19 years old and spoke no English; no one on board could translate for him, but he pointed to the roll of his hair, signifying he was a Crow scout and not an attacking Lakota or Cheyenne, repeating “Absaroke! Absaroke!” (rendered as ‘Crow’ in English but extending to comrade soldiers). The men recognized Curley, one of the Crows who had gone off with Custer. As he came aboard, it was clear to Grant Marsh, the Far West’s pilot and captain, that he was overwhelmed: “Throwing himself down upon a medicine-chest on deck,” wrote Marsh’s biographer, “he began rocking to and fro, groaning and crying.”

Since Curley could not easily communicate with the men, the enormity of what he had seen (and guessed at looking back toward the battlefield) would be told through a clumsy process of pantomime and drawing:

“At the steamer I told of Custer’s defeat by sticking little sticks in the ground and then sweeping them away with my hand. I also pointed at the sticks and made motions like scalping by pulling at my own hair and groaning, but the soldiers were dull and did not appear to understand me. I did this on top of a box.”

He mimed sleep for death, made explosive sounds while thudding his chest. Finally given a pencil and sheet of paper, he drew two circles, one much larger than the one it surrounded, showing how Custer’s men had been encircled; filling the blank space with dots for the many attacking warriors, Curley declared, ‘Sioux! Sioux!’. His listeners came to grasp his alarming message; a doubtful officer ordered him back to the battle scene to verify all were dead, but Curley refused. The tremendous gunfire coming at the soldiers had sounded, he recalled, like “the snapping of the threads in the tearing of a blanket.”

Soldiers from Capt. Reno’s command began to arrive on June 9th; wounded men from the fighting on what became Reno Hill were loaded aboard, and over several days and nights Captain Grant Marsh navigated 710 miles along three rivers with his precious cargo. Draped in black, the boat finally brought word of the 7th cavalry’s disaster to Bismarck late on the night of July 5th, where the news went out on the wires. The Bismarck Tribune’s July 6th extra noted that of those who went into battle with Custer, “none are living –one Crow scout hid himself in the field and witnessed and survived the battle. His story is plausable…” On July 11, the scout appeared in the New York Herald, a young man who, after telling his story, sat “dejected and apparently deep in thought,” humming a Crow tune. By July 20th, he was identified as the lone survivor “from the terrible butchery in which the daring Custer and his gallant command laid down their lives.” The last stand had begun.

v.

Tramp actor: Ben’s second term at Leavenworth

Tramp actor: Ben’s second term at Leavenworth

By 1916, Ben McIntosh was wanted in ten states, pursued by a man named Leon Bone, when he made the mistake of marrying a woman who did not like to be fooled. Con men favored stealthy exits, and marrying might seem to restrict one’s motion. But the rumor of money must have seemed worth the risk for Ben when he courted a woman he met in Indianapolis that summer of 1916. Now in his 70s, Ben was described in warrants as 5 foot 8, about 160 pounds, “swarthy” or “half-breed”, slightly stooped and a “quarrelsome” drinker.

Retta (Loretta) Moss was said to be wealthy; the 1910 census lists her simply as a black woman with several boarders, working as a dresser using ostrich feathers. Her friends suspected the newcomer, who met Retta while staying at her friend’s house, where he entertained visitors with stories of his frontier experiences and claimed to be a rich landowner. Following a wedding in Retta’s house, he quickly proposed a honeymoon in Washington, DC, where he could combine pleasure with official business, delivering important news to the President.

While he did not see the President in Washington, he would meet the Secret Service. It is possible the Justice Department had been tipped off by McIntosh’s name appearing on the couple’s wedding registration, along with their honeymoon destination. For as the couple visited the Capital, service agents called on the new Mrs. McIntosh at the hotel. Ben was out for a long morning walk as she learned that the genuine Curley lived far away in Montana and she had married a charming counterfeit. Her anger grew waiting for Ben’s return, when he was arrested. Retta soon took the train back home to Indianapolis. “We had only been married about three weeks and on a short acquaintance,” Ben told reporters. “If it hadn’t been for my infatuation for that woman I wouldn’t be where I am today. I would have had my business done and been out of Washington before I was arrested, if I hadn’t stopped to get married.”

McIntosh was finally indicted not for crimes against history but for “Personating a government agent,” a charge he did not contest. On his way into the Leavenworth courtroom, the wife of a Topeka jeweler recognized on Ben’s finger the ring she had given him in exchange for some reservation land. From the bench, the Judge explained that he hoped, being a man in his 70s, McIntosh planned to conduct himself “as a good man hereafter.”

“I am a good man right now,” he answered. “I have embraced Christianity and am living a Christian life.” In fact, he was still the man who could look into the eyes of Native people in California and Nevada, telling them they were about to be moved by the government but he could save them the best plots on their new reservation for a price.

He was sentenced to serve a year at Leavenworth Penitentiary for his crimes in Topeka, to be followed by trials in other states. In October 1916 he entered Leavenworth as ‘prisoner 11277,’ still identified as “Ben McIntosh, alias ‘Curley,’’’ a ‘farmer’ who claimed four daughters and eleven sons; by his second term, he would list five boys and six girls, a loss of six sons.

His jailers didn’t know who he truly was, just that he looked ‘Indian’ if not the particular Indian he claimed. When he left the prison a year later, deputy marshals from Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah competed to take possession of the con man for similar trials in their own states. After a separate trial, he was returned to Leavenworth to serve another term.

In May 1918, he was met at the Leavenworth gate by a marshal to take him to Salt Lake City, where prosecutors advised a more lenient sentence, as he might not survive a regular term. Sensing sympathy in the room, Ben informed the judge that a childhood brain injury made him sometimes adopt the role of a Custer survivor or land agent. (His prison sheet in fact documented a soft spot on his skull.) The judge gave him 30 days.

After his prison terms, he was 77 years old and had made (and lost) considerably more money from Curley’s name than Curley ever had: “at least $50,000,” estimated the secret service. But only weeks after his score in Topeka, he was passing bad checks in Salt Lake City, if just for the grifty thrill. By 1919, after his prison service in Kansas he returned there to lecture in Hays, reporting that Mrs. Custer had taught him to read and write, and that he had spent several years after the battle traveling with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West before “retiring” to his farm.

In April 1921, he collapsed in the early morning on the platform of the Union Station in Ogden, Utah, the site of his earliest recorded Curley impersonation. Detectives took him to a hospital, where it was reported he had complications from an earlier gall stone surgery. An obituary was readied, wrapping him in the fabrications of his borrowed legend, “Ben McIntosh, 80 years old, one of the pioneers of the West.” Words from Ben’s performances as Curley still turn up in histories and museum installations, and a battle map he drew lives on the credulous internet.

Curley by Richard Throssel (LOC)

Curley by Richard Throssel (LOC)

The real Curley would die of pneumonia in 1923, months after the con man who had long dined out on his name. He was buried near his home at Custer National Cemetery, among the other Crow scouts. But Curley’s cabin was moved from the Crow Agency to the historical village assembled in Cody, Wyoming, Old Trail Town. In the way of the legendary West, you can see it there along with cabins used by the Hole in the Wall gang and the grave of the mountain man John Johnson.

___________________________________