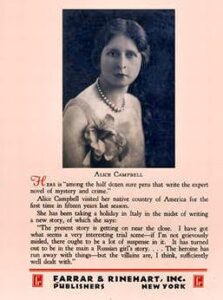

In 1927 Alice Dorothy Ormond Campbell—a thirty-nine-year-old native of Atlanta, Georgia who for the last fifteen years had lived successively in New York, Paris and London, never once returning to the so-called Empire City of the South—published her first novel, an unstoppable crime thriller called Juggernaut, selling the serialization rights to the Chicago Tribune for $4000 ($60,000 today), a tremendous sum for a brand new author. On its publication in January 1928, both the book and its author caught the keen eye of Bessie S. Stafford, society page editor of the Atlanta Constitution, a genteel southern lady who seemingly, like the Bourbons of France, had forgotten nothing. Back when Alice Ormond, as she was then known, lived in Atlanta, Miss Bessie breathlessly informed her readers, she had been “an ethereal blonde-like type of beauty, extremely popular, and always thought she was in love with somebody. She took high honors in school; and her gentleness of manner and breeding bespoke an aristocratic lineage. She grew to a charming womanhood—”

Let us stop Miss Bessie right there (we will be seeing her again later), because as you may cynically have guessed, there is rather more to the story of the once prominent and still intriguing vintage Anglo-American crime novelist Alice Campbell—the mystery genre’s other “AC,” who published nineteen crime novels between 1928 and 1950—than her vaunted ethereal beauty and good breeding (though, to be sure, there is something to that as well). So allow me to plunge boldly forward with the fascinating tale of Atlanta’s great Golden Age crime writer, who as an American expatriate in England, like her younger contemporary John Dickson Carr, went on to achieve fame and fortune as an atmospheric writer of crime and mystery and become one of the early members of the Detection Club.

Although Alice Campbell’s lineage may not have been “aristocratic,” this word almost invariably being misapplied in an American context, it was to no small degree distinguished. Alice was born in Atlanta on November 29, 1887, the youngest of the four surviving children of prominent Atlantans James Ormond IV and Florence Root. Both of Alice’s grandfathers, James Ormond III of Florida and Sidney Dwight Root of Massachusetts, had been wealthy Atlanta merchants who settled in the city in the years leading up to the American Civil War.

James Ormond III’s grandfather, James Ormond I, was a Scottish sea captain who in 1804, after many adventures, seafaring and otherwise, established “Damietta,” a two thousand acre cotton and indigo plantation in the east-central section of what was then Spanish Florida. The first James Ormond was murdered by a runaway slave in 1817, but a few years later his son and daughter-in-law, Isabella Christie, returned to Damietta and reestablished the plantation. (Isabella’s presence in Alice Campbell’s family tree means that theoretically she could be related to Agatha Christie’s first husband Archie, whose paternal grandfather, incidentally, was named Campbell Christie.) James Ormond II died at Damietta in 1829 and was entombed on its grounds, his survivors removing to Charleston, South Carolina. Today thirteen-acre James Ormond Tomb Park is all that remains of the once sprawling plantation, which was destroyed by Native Americans during the Second Seminole War—although the city of Ormond Beach, Florida named in honor of the family, stands as well as a grander tribute. James Ormond III returned to Florida to fight, for the good of the family name, during the Second Seminole War, serving as an officer in the so-called Mosquito Roarers, a Florida militia. At the war’s conclusion he married a daughter of Benjamin Chaires, the builder of Verdura, said to have been antebellum Florida’s most opulent plantation.

James Ormond III himself rose to wealth and prominence after he removed to Atlanta, among many enterprises founding the Atlanta Paper Mill, of which his son, Alice’s father James Ormond IV, later served as superintendent. In 1873 James IV wed Florence Root, with whom he fathered two sons and two daughters who grew to adulthood, including Alice, the pampered baby of the Ormond brood. Florence was one of the children of Sidney Dwight Root, a native of Massachusetts who settled in Georgia in the 1840s, later moving to Atlanta and becoming a co-partner in Beach, Root & Company, the most lucrative business firm in antebellum Atlanta. During the Civil War, the firm set up an office in Liverpool, England and with its merchant vessels successfully ran the Union naval blockade of the South. Root himself traveled in person to England and France, where he promoted the desperate idea of emancipating slaves in return for their military service in the Confederate Army, in the hope of drawing English recognition of the Confederate States of America. There he meant such pro-Southern sympathizers as the Marquis of Bath at his country seat, Longleat (the home of the family of Golden Age mystery writer Molly Thynne), Lord Derby and “an intense Confederate Englishman by the name of Campbell”—no ancestral relation, evidently, to Alice’s future husband.

Alice’s uncles John Wellborn and Walter Clark Root were noted American architects. When John Wellborn Root died at the age of forty-one in 1891, when Alice was but three years old, he and his partner Daniel Burnham, designers of the Rookery, then considered the finest office building in the United States, had been in the preliminary stages of planning the Chicago World’s Fair (aka the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893). Walter C. Root, fated to be known as the “other Root brother,” rose to prominence in Kansas City, Missouri and remained active there until his death in 1925, less than three years before Alice published Juggernaut.

In contrast with her two uprooted uncles, Alice’s pair of prominent brothers, Sidney James and Walter Emanuel Ormond—who respectively were fourteen and twelve years older than she—remained in Atlanta. Sidney James Root served as a drama critic and political writer for the Atlanta Constitution and in the latter capacity covered the infamous Leo Frank murder trial in 1913, which transfixed the American nation and haunts it still today. Leo Frank, a Jewish superintendent of an Atlanta pencil factory on trial for the murder of Mary Phagan, a pretty, thirteen-year-old white employee, was convicted, sentenced to death and—after his death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment by the governor in 1915—hanged at the age of thirty-one by a lynch mob which included the immediately previous governor of the state.

Outside of the South the whole affair was widely deemed a monstrous miscarriage of justice. Today it is generally believed that Mary Phagan was murdered by factory sweeper Jim Conley, who was the state’s star witness against Leo Frank at the trial. At the time of Sidney Root’s own untimely death the next year at the age of forty-two, he was at the apex of his career, serving as personal secretary to Atlanta Mayor James G. Woodward, who in 1915 had pugnaciously rationalized Frank’s lynching before a non-southern audience by asserting that three-quarters of the state of Georgia thought the man was guilty and “when it comes to a [southern white] woman’s honor, there is no limit that we [southern white men] will not go to protect it.” Alice, who was married and living in England at this time, did not return to Atlanta for her unmarried brother’s funeral.

Alice’s other brother, Walter Emanuel Ormond, an Atlanta attorney and justice of the peace, suffered an even more untimely death than his brother when, in 1906 at the age of thirty, he fell overboard to his death from the steamer Kansas City, en route from Savannah to New York, somewhere near Cape Hatteras, off the cost of North Carolina. Earlier in the evening, after considerable drinking one surmises, Walter in his capacity as a JP had performed a mock marriage ceremony, demanding as a fee the bracelet worn by the “bride,” which he placed around his own left wrist. Later, restless and hot on that sweltering July night in his upper deck state room, which he reportedly shared with an “intimate” male friend, Walter, clad in his pajamas, stalked out and went to sleep in a steamer chair on the deck. The Atlanta Constitution speculated, more euphemistically than I am putting it, that Walter while vomiting over the deck rail lost his balance and toppled headlong into the ocean, where he drowned. The paper expressed the hope, which came to naught, that Walter’s body would be identified by the woman’s bracelet encircling his wrist. At the time of his demise Walter was unmarried and lived with his mother and sister. Alice’s sister Mary Florence, a decade older than she, had wed six years earlier to insurance executive Hinton Hopkins, a son of the first president of the Georgia Institute of Technology, aka Georgia Tech. Like Alice, Mary was deemed a “beauty of the fairest and daintiest type of blonde.”

Both Alice and her sister managed to dodge the Reaper’s scythe that repeatedly struck down their menfolk in the prime of their lives. Alice was raised by her mother after Florence and James Ormond divorced some time prior to Mary’s marriage in 1900, before Alice was even a teenager, although Florence, evidently seeking to avoid the ignominy that inevitably attended a divorcee in the Victorian era, no matter the circumstances of the divorce, listed herself as a widow in city directories. James seems to have become a nonperson to his family afterward, not even receiving mention in his daughter Mary’s marriage notices in the Atlanta Constitution, despite the fact that he was still alive and residing in the city, living with a sister and brother-in-law, with apparently no occupation, though he was only in his fifties. At her wedding Mary was given away not by an adoring father, but by her surviving maternal uncle from St. Louis, Walter C. Root. Had James as a husband been alcoholic, adulterous, even abusive? Evidently the dirty laundry of an unamicable parting between representatives of the socially prominent Ormonds and Roots was not something which the Constitution felt inclined to air before its readers.

Both Alice and her sister managed to dodge the Reaper’s scythe that repeatedly struck down their menfolk in the prime of their lives. Alice was raised by her mother after Florence and James Ormond divorced some time prior to Mary’s marriage in 1900, before Alice was even a teenager, although Florence, evidently seeking to avoid the ignominy that inevitably attended a divorcee in the Victorian era, no matter the circumstances of the divorce, listed herself as a widow in city directories. James seems to have become a nonperson to his family afterward, not even receiving mention in his daughter Mary’s marriage notices in the Atlanta Constitution, despite the fact that he was still alive and residing in the city, living with a sister and brother-in-law, with apparently no occupation, though he was only in his fifties. At her wedding Mary was given away not by an adoring father, but by her surviving maternal uncle from St. Louis, Walter C. Root. Had James as a husband been alcoholic, adulterous, even abusive? Evidently the dirty laundry of an unamicable parting between representatives of the socially prominent Ormonds and Roots was not something which the Constitution felt inclined to air before its readers.

Alice precociously published her first piece of fiction, a fairy story titled “Ambitious Allen and Pretty Annette,” in the Atlanta Constitution in 1897, when she was nine years old. Four years later, Alice, herself pretty like Annette and ambitious like Allen, was in the final stage of completing a two-volume novel. By 1905 she was an honored graduate of Atlanta’s Girls’ High School and a nationally published poet, having appeared in an anthology along with another talented teen, native Pennsylvanian Miriam Allen deFord, a future Edgar Award winning true crime writer. By this time Alice attended the Church of Our Father, Atlanta’s only Unitarian house of worship, and served as corresponding secretary of the Southern Associate Alliance, a branch of the National Alliance of Unitarian and Other Liberal Christian Women. Two years later, nineteen-year-old Alice, having found Atlanta too narrow a canvas for her large-scale literary and social ambitions, had relocated to New York, safely chaperoned by Florence.

Together mother and daughter took up residence at Manhattan’s Yorston Hotel, overlooking Central Park, which had been started by three native Atlantan sisters to cater to fellow Atlantans who had moved, like Alice, to New York to launch business or artistic careers. There Alice became friends with writers Inez Haynes Irwin, a prominent feminist, and Jacques Futrelle, the creator of “The Thinking Machine” detective who was soon to go down with the ship on RMS Titanic, and scored her first published short story in Ladies Home Journal in 1911. Simultaneously she threw herself pell-mell into the causes of women’s suffrage and equal pay for equal work, topics which in 1912 she returned to Atlanta to discourse upon before an audience of assembled natives. Feminism was not just a cause of eccentric, elderly spinsters, she explained, but young women, married women and married women’s supportive husbands too. The same year she herself became engaged in New York to marry Burnet C. Tuthill, a music student at Columbia University and son of architect William Tuthill (the designer of New York’s famed Carnegie Hall and an acquaintance of Alice’s uncles) who later founded the Memphis Symphony Orchestra. However, the couple soon broke off their engagement and in February 1913 Alice went off to Paris with her mother to further her cultural education.

Three months later in Paris, on May 22, 1913, twenty-five-year-old Alice—who as a girl in Atlanta, it will be recalled, “always thought she was in love with somebody”—married James Lawrence Campbell, a twenty-four-year-old theatrical agent of good looks and good family from the American state of Virginia. Jamie, as he was familiarly known, had arrived in Paris a couple of years earlier, after a failed stint in New York City as an actor. “A Virginia ham is all right in its place,” joked a friend of Jamie’s struts upon the stage. A photo of him from probably about fifteen years later calls to my mind something of an amalgam of actors Michael York and Joel Gray from the film Cabaret. In Paris he served, more successfully, as an agent for prominent New York play brokers Arch and Edgar Selwyn.

Three months later in Paris, on May 22, 1913, twenty-five-year-old Alice—who as a girl in Atlanta, it will be recalled, “always thought she was in love with somebody”—married James Lawrence Campbell, a twenty-four-year-old theatrical agent of good looks and good family from the American state of Virginia. Jamie, as he was familiarly known, had arrived in Paris a couple of years earlier, after a failed stint in New York City as an actor. “A Virginia ham is all right in its place,” joked a friend of Jamie’s struts upon the stage. A photo of him from probably about fifteen years later calls to my mind something of an amalgam of actors Michael York and Joel Gray from the film Cabaret. In Paris he served, more successfully, as an agent for prominent New York play brokers Arch and Edgar Selwyn.

The Atlanta Constitution carried the happy announcement of the comely young couple’s nuptials on page eight, the front page of the newspaper being devoted, naturally, to the state’s latest crime outrages, notably the Leo Frank case—Atlanta police had just arrested and dragged off to prison the Franks’ hysterical, “high yellow” cook, Minola McKnight, in an effort to extract incriminating evidence against her employer—as well as a narrowly averted lynching of a couple of county black men accused of murdering a white woman. Florence’s duty to her daughter done, the devoted mother returned to Atlanta, where Mary still resided, and passed away there five years later at the age of sixty-four, possibly a victim of the Spanish Flu pandemic then wracking the world. The tablet over Florence’s grave memorializes as well her dear lost son Walter, “drowned at sea.” James Ormond had predeceased his ex-wife in 1911, expiring at his sister’s home in Atlanta after having suffered a paralytic stroke on a visit two years earlier to Ormond Beach, the cite of his forbears’ faded glory. Sidney Ormond of course died five years later. Obviously one reason Alice so long put off returning to Atlanta was that she had so little left to return to there and yet so much still to prove.

*******

After the wedding Alice Ormond Campbell, as she now was known, remained in Paris with her husband Jamie until hostilities between France and Germany loomed direfully the next year. At this point the couple prudently relocated to England, along with their newborn son, James Lawrence Campbell, Jr. After the war the Campbells, living in London, bought an attractive house on Albion Road, in the district of St. John’s Wood, Westminster, where they established a literary and theatrical salon. There Alice oversaw the raising of the couple’s two sons, Lawrence and Robert, and their single daughter, Florence Ormond, while Jamie spent much of his time abroad, brokering play productions in Paris, New York and other cities.

Like Alice, Jamie harbored dreams of personal literary accomplishment; and in 1927 he published, in the United Kingdom and United States, a novel entitled Face Value, which for a brief time became that much-prized thing by publishers, a “scandalous” novel that gets Talked About. The story of a gentle orphan boy named Serge, the son an emigre Russian prostitute, who grows up in a Parisian “disorderly house,” as reviews often blushingly put it, Face Value divided critics, impressing many of them with is refreshing frankness while merely scandalizing others. While provincial Dayton, Ohio reviewer Varley P. Young, for example, groused of the novel that “[f]rom the first paragraph until the last, the reader is never allowed to forget the sordid background of the story” and sneered that other reviewers would pronounce it “an important’ book” merely because “it dispels the illusions of mankind and brings to surface the sewage of life,” as perceptive an audience as the great American novelist Willa Cather was captivated by it, writing a friend, playwright Zoe Akins: “Zoe, I’m going to send you a book which has interested me a lot. I don’t usually like books about houses of prostitution, or comparisons of English and French manners, and this book is made of those two things; but I like it. The man really has something to say. It’s called ‘Face Value.’ Please read it carefully—it’s good somehow. I don’t know why.”

Read it people did, and Face Value ended up on American bestseller lists. Jamie went on to publish two more novels, The Miracle at Peille (1929), likewise set in France, and Success and Plenty (1930), set in England, but neither work received anything like the attention Face Value had, making Jamie, as a novelist at least, a one-hit wonder. The success of his first novel led to the author being invited out to Hollywood to work as a scriptwriter, and his name appears on credits to a trio of films in 1927-28, including French Dressing, a “gay” divorce comedy set among sexually scatterbrained Americans in Paris. One wonders whether in Hollywood Jamie ever came across future crime writer Cornell Woolrich, who was scripting there too at the time.

Meanwhile Alice remained in England with the children, enjoying her own literary splash in warm waters with her debut thriller Juggernaut, which concerned the murderous machinations of an inexorably ruthless French Riviera society doctor, opposed by a valiant young nurse. The novel racked up rave reviews and sales in the UK and US, in the latter country spurred on by its nationwide newspaper serialization, which promised readers

Meanwhile Alice remained in England with the children, enjoying her own literary splash in warm waters with her debut thriller Juggernaut, which concerned the murderous machinations of an inexorably ruthless French Riviera society doctor, opposed by a valiant young nurse. The novel racked up rave reviews and sales in the UK and US, in the latter country spurred on by its nationwide newspaper serialization, which promised readers

….the open door to adventure! Juggernaut by Alice Campbell will sweep you out of the humdrum of everyday life into the gay, swift-moving Arabian-nights existence of the Riviera!

London’s Daily Mail declared that the irresistible Juggernaut “should rank among the ‘best sellers’ of the year”; and, sure enough, Juggernaut’s English publisher, Hodder & Stoughton, boasted, several months after the novel’s English publication in July 1928, that Hodder already had run through six printings in an attempt to satisfy customer demand for ructions on the Riviera, something English thriller writer E. Phillips Oppenheim had made a fortune supplying the public for over three decades. In 1936 Juggernaut was adapted in England as a film vehicle for horror great Boris Karloff, making it the only Alice Campbell novel filmed to date. The film was remade in England under the title The Temptress in 1949.

Contrasting with Jamie’s sober-sided novels, Alice’s Water Weed (1929) and Spiderweb (1930) (Murder in Paris in the US), the immediate successors to her debut shocker, held up well to their predecessor’s performance. Alice, now in her forties, finally saw her career as a writer triumphantly launched. She chose this moment to return for a fortnight to Atlanta, ostensibly to visit her sister at her $30,000 (about $465,000 today) colonial home on Fairview Road, but doubtlessly in part to parade through her hometown as a conquering, albeit commercial, literary hero. And who was there to welcome Alice in the pages of the Constitution but Bessie S. Stafford, who pronounced Alice’s hair still looked like spun gold while her eyes remarkably had turned an even deeper shade of blue. To Miss Bessie, Alice imparted enchanting tales of salon chats with such personages as George Bernard Shaw, Lady Cynthia Asquith, H. G. Wells and (his lover) Rebecca West, the latter of whom a simpatico Alice met and conversed with frequently. Admitting that her political sympathies in England “inclined toward the conservatives,” Alice yet urged “the absolute necessity of having two strong parties.” English women, she had been pleased to see, evinced more informed interest in politics than their American sisters.

Alice, Bessie declared, doted on her children: sixteen-year-old Lawrence, a student at prestigious Westminster School; fourteen-year-old Ormond, her only daughter, a blonde like her mother who liked poetry and attended Francis Holland School for Girls; and twelve-year-old Robert, enraptured with electrical engineering and “enrolled in a modern coeducational boarding school.” Yet their mother diligently devoted every afternoon to her writing, shutting her study door behind her “as a sign that she is not to be interrupted.” This commitment to her craft enabled Alice to produce an additional sixteen crime novels between 1932 and 1950, beginning with The Click of the Gate and ending with The Corpse Had Red Hair.

Although nearly half of Alice’s crime novels were standalones, in contravention of convention at this time, when series sleuths were so popular, with The Click of the Gate the author introduced one of her main recurring characters, intrepid Paris journalist Tommy Rostetter, who appears in three additional novels: Desire to Kill (1934), Flying Blind (1938) and The Bloodstained Toy (1948). In the two latter novels, Tommy appears with Alice’s other major recurring character, dauntless Inspector Headcorn of Scotland Yard, who also pursues murderers and other malefactors in Death Framed in Silver (1937), They Hunted a Fox (1940), No Murder of Mine (1941) and The Cockroach Sings (1946) (With Bated Breath in the US).

Although nearly half of Alice’s crime novels were standalones, in contravention of convention at this time, when series sleuths were so popular, with The Click of the Gate the author introduced one of her main recurring characters, intrepid Paris journalist Tommy Rostetter, who appears in three additional novels: Desire to Kill (1934), Flying Blind (1938) and The Bloodstained Toy (1948). In the two latter novels, Tommy appears with Alice’s other major recurring character, dauntless Inspector Headcorn of Scotland Yard, who also pursues murderers and other malefactors in Death Framed in Silver (1937), They Hunted a Fox (1940), No Murder of Mine (1941) and The Cockroach Sings (1946) (With Bated Breath in the US).

Additional recurring characters in Alice’s books are Geoffrey Macadam and Catherine West, who appear in Spiderweb and No Light Came On (1942), and Colin Ladbrooke, who appears in Death Framed in Silver, A Door Closed Softly (1939) and They Hunted a Fox. In the latter two books Colin with his romantic interest Alison Young and in the first and third book with Inspector Headcorn, who also as mentioned appears in Flying Blind and The Bloodstained Toy with Tommy Rosstetter, making Headcorn the connecting link in this universe of sleuths, although the inspector does not appear with Geoffrey Macadam and Catherine West. It is all a rather complicated state of criminal affairs; and this lack of a consistent and enduring central sleuth character in Alice’s crime fiction may help explain why her work faded in the Fifties, after the author retired from writing.

Be that as it may, Alice Campbell is a figure of significance in the history of crime fiction. In a 1946 review of The Cockroach Sings in the London Observer, crime fiction critic Maurice Richardson, in the course of explaining why “[w]e can always do with Mrs. Alice Campbell,” asserted that “[s]he belongs to the atmospheric school, of which one of the outstanding exponents was the late Ethel Lina White,” the author of The Wheel Spins (1936), famously filmed in 1938, under the title The Lady Vanishes, by director Alfred Hitchcock. This “atmospheric school,” as Richardson termed it, had more students in the demonstrative United States than in the decorous United Kingdom, to be sure, the United States being the home of such hugely popular suspense writers as Mary Roberts Rinehart and Mignon Eberhart, to name but a couple of the most prominent examples.

Like the novels of the American Eber-Rinehart school and English authors Ethel Lina White and Marie Belloc Lowndes, the latter the author of the acknowledged landmark 1911 thriller The Lodger, Alice Campbell’s books are not pure puzzle detective tales, but rather broader mysteries which put a premium on the storytelling imperatives of atmosphere and suspense. “She could not be unexciting if she tried,” raved the Times Literary Supplement of Alice, stressing the author’s remoteness from the so-called “Humdrum” school of detective fiction headed by British authors Freeman Wills Crofts, John Street and J. J. Connington. However, as Maurice Richardson, a great fan of Alice’s crime writing, put it, “she generally binds her homework together with a reasonable plot,” so the “Humdrum” fans out there need not be put off by what American detective novelist S. S. Van Dine, creator of Philo Vance, dogmatically dismissed as “literary dallying.” In her novels Alice Campbell offered people bone-rattling good reads, which explains its popularity in the past and its revival today. Lines from a review of her 1941 crime novel No Murder of Mine by “H.V.A.” in the Hartford Courant suggests the general nature of her work’s appeal: “The excitement and mystery of this Class A shocker start on page 1 and continue right to the end of the book. You won’t put it down, once you’ve begun it. And if you like romance mixed with your thrills, you’ll find it here.”

The protagonist of No Murder of Mine is Rowan Wilde, “an attractive young American girl studying in England.” Frequently in her books Alice, like the great Anglo-American author Henry James, pits ingenuous but goodhearted Americans, male or female, up against dangerously sophisticated Europeans, drawing on autobiographical details from her and Jamie’s own lives. Many of her crime novels, which often are lengthier than the norm for the period, recall, in terms of their length and content, the Victorian sensation novel, which seemingly had been in its dying throes when the author was a precocious child; yet, in their emphasis on morbid psychology and their sexual frankness, they also anticipate the modern crime novel. One can discern this tendency most dramatically, perhaps, in the engrossing Water Weed, concerning a sexual affair between a middle-aged Englishwoman and a young American man that has dreadful consequences, and Desire to Kill, about murder among a clique of decadent bohemians in Paris. In both of these mysteries the exploration of aberrant sexuality is striking. Indeed, in its depiction of sexual psychosis Water Weed bears rather more resemblance to, say, the crime novels of Patricia Highsmith than it does to the cozy mysteries of Patricia Wentworth. One might well term it Alice Campbell’s Deep Water, recalling Highsmith’s third crime novel.

The protagonist of No Murder of Mine is Rowan Wilde, “an attractive young American girl studying in England.” Frequently in her books Alice, like the great Anglo-American author Henry James, pits ingenuous but goodhearted Americans, male or female, up against dangerously sophisticated Europeans, drawing on autobiographical details from her and Jamie’s own lives. Many of her crime novels, which often are lengthier than the norm for the period, recall, in terms of their length and content, the Victorian sensation novel, which seemingly had been in its dying throes when the author was a precocious child; yet, in their emphasis on morbid psychology and their sexual frankness, they also anticipate the modern crime novel. One can discern this tendency most dramatically, perhaps, in the engrossing Water Weed, concerning a sexual affair between a middle-aged Englishwoman and a young American man that has dreadful consequences, and Desire to Kill, about murder among a clique of decadent bohemians in Paris. In both of these mysteries the exploration of aberrant sexuality is striking. Indeed, in its depiction of sexual psychosis Water Weed bears rather more resemblance to, say, the crime novels of Patricia Highsmith than it does to the cozy mysteries of Patricia Wentworth. One might well term it Alice Campbell’s Deep Water, recalling Highsmith’s third crime novel.

In this context it should be noted that in 1935 Alice Campbell authored a sexual problem play, Two Share a Dwelling, which the New York Times described as a “grim, vivid, psychological treatment of dual personality.” Although it ran for only twenty-two performances during October 8-26 at the West End’s celebrated St. James’ Theatre, the play had done well on its provincial tour and it received a standing ovation from the audience on opening night at the West End, primarily on account of the compelling performance of the half-Jewish German stage actress Grete Mosheim, who had fled Germany two years earlier and was making her English stage debut in the play’s lead role of a schizophrenic, sexually compulsive woman with two polar personalities: Lilia, “a shrinking, sensitive creature with a disturbing suggestion of mental fragility,” and Bess, “a brazen harlot.” Mosheim was described as young and “blondely beautiful,” bringing to mind the author herself.

At its Glasgow tryout, the play was greeted with unqualified praise, one critic declaring that the writing was “so psychologically sound it would satisfy Freud”; and no fewer than “nine curtain calls greeted the cast and author.” Unfortunately London critics were put off by the play’s sexual subject, which put Alice in an impossible position with them. One reviewer scathingly observed that “Miss Alice Campbell…has chosen to give her audience a study in pathology as a pleasant method of spending the evening….it is always a distressing sight to see a struggle between good and evil….one leaves the theatre rather wishing that playwrights would leave medical books on their shelves.” Another sniffed that “it is to be hoped that the fashion of plumbing the depths of Freudian theory for dramatic fare will not spread. It is so much more easy to be interested in the doings of the sane.” The play died a quick death in London and its author went back, for another fifteen years, to “plumbing the depths” in her crime fiction.

What impelled Alice and Jamie Campbell so avidly to explore human sexuality in their work? Doubtless their writing reflected the temper of modern times, but it also likely was driven by personal imperatives. The child of an unhappy marriage who at a young age had been deprived of a father figure, Alice appears to have wanted to use her crime fiction to explore the human devastation wrought by disordered lives. For his part globetrotting, cosmopolitan Jamie Campbell came, seemingly paradoxically, from a genteel old southern family from the piedmont region of Virginia and a country town, Bedford, of fewer than three thousand souls. His father, James Lawrence Campbell, Sr., was a respected lawyer, mayor, state senator and circuit judge who died in 1914, the year after Jamie’s marriage. Yet Jamie’s mother, Lillian (Bowyer) Campbell, had passed away nearly two decades earlier at the age of thirty-four, likely from the effects of a difficult childbirth, leaving his father with the responsibility for raising the couple’s four young surviving children: Thomas, eight, Jamie, six, George, four, and Lillian, one.

A pair of the judge’s spinster sisters attempted daintily to step into the breach left by Lillian’s untimely demise, but at least one of the Campbell children, daughter Lillian, went decidedly wayward, in 1913 eloping at the age of eighteen with her beau, Thomas Berry, a son of a local banker and tobacco planter. For some months Judge Campbell had endeavored to put an end to his young daughter’s love affair, and a few weeks before the elopement he had personally hauled Lillian to the State Normal and Industrial School for Women, about one hundred miles to the north of Bedford in the Shenandoah Valley town of Harrisonburg, and proceeded to enroll her there, where she was to stay pending completion of arrangements to pack her off to Paris, where her brother Jamie, who himself would marry Alice in three months, was now located. This setup makes the Normal School sound more like a girls’ reformatory or prison than a hallowed institution of learning, and Lillian, a spirited girl, was having none of it.

Around four in the morning on Valentine’s Day, February 14, Lillian lowered herself from her dormitory window on a rope made from bedsheets, met her lover and fled with him to the train station, where they boarded for Washington, D. C. and wed, before seemingly vanishing into thin air. This youthful outburst of esprit d’amour made for wryly amused national newspaper headlines, such as “Maid Outwits City Judge, Her Father,” but unfortunately Lillian and Thomas Berry did not live happily ever after together. The couple moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where Lillian rapidly gave birth to four daughters and Thomas worked as an advertising salesman. By 1930 the man and wife had divorced and Thomas had left for Gulfport, Mississippi, where he remarried. Left with the care of four daughters, Lillian found employment in Milwaukee as a public librarian. She died in 1941 at the age of forty-six, but surviving photographs of her show a smiling woman, lovingly surrounded by her daughters.

Jamie’s brother Thomas Bowyer Campbell also very much chose his own path in life. An Episcopalian minister, former China missionary and prominent member of the Anglo-Catholic Group in the Episcopal Church, Thomas made national headlines by converting to Catholicism in 1931 and becoming a Catholic priest. He had been living in England for the last three years, officiating at Anglican ceremonies at Oxford, and like his brother Jamie and sister-in-law Alice at this time, he was bitten by the literary bug. He published a quartet of novels: Black Sadie (1928), a tale of black life in Virginia and Harlem, Old Miss (1929), a story set in antebellum Virginia that he based on the life of his great-grandmother, Far Trouble (1931), a thriller set in China, and White Nigger (1932), a miscegenation novel that he had submitted to publishers under the less attention-grabbing title Sweet Chariot in 1930. (To his credit he admitted his embarrassment with the title under which the book was published.)

Evidence suggests that discord had entered the lives of Alice and Jamie at least as early as the 1930s, when the couple had reached middle age and their children had entered adulthood. After the First World War, when Alice and Jamie produced their trio of children, it appears that they spent a great deal of time apart, and it is not hard to imagine that Jamie, at least, carried on sexual liaisons with others. Alice’s life, on the other hand, seems to have settled down considerably from those heady early days in Paris and London. In 1939, as the Second World War loomed, Alice resided in rural southwestern England with her daughter Ormond at a cottage—the inspiration for her murder setting in No Murder of Mine, one guesses—near the bucolic town of Beaminster, Dorset, known for its medieval Anglican church and its charming reference in a poem by English dialect poet William Barnes:

Sweet Be’mi’ster, that bist a-bound

By green and woody hills all round,

Wi’hedges, reachen up between

A thousand vields o’ zummer green.

Alice’s elder son Lawrence, living unemployed in New York City at this time, would enlist in the US Army when the country entered the war a couple of years later, serving as a master sergeant throughout the conflict. In December 1939, twenty-three-year-old Ormond, who herself preferred going by the name Chita, her father’s pet name for her, wed the prominent antiques dealer, interior decorator, home restorer and racehorse owner Ernest Thornton-Smith, who at the age of fifty-eight was fully thirty-five years older than she. Thornton-Smith and his similarly occupied brother, Walter, appear to have been modestly born “Smith,” sons of civil servant Samuel Tomas Smith, but under the posher moniker “Thornton-Smith,” they both made fortunes catering to the tastes of England’s rich and privileged. Suggestive of estrangement from her husband, Ormond in 1967 would officially change her name by deed poll from Florence Ormond Thornton-Smith to Chita Florence Ormond Campbell.

Alice’s elder son Lawrence, living unemployed in New York City at this time, would enlist in the US Army when the country entered the war a couple of years later, serving as a master sergeant throughout the conflict. In December 1939, twenty-three-year-old Ormond, who herself preferred going by the name Chita, her father’s pet name for her, wed the prominent antiques dealer, interior decorator, home restorer and racehorse owner Ernest Thornton-Smith, who at the age of fifty-eight was fully thirty-five years older than she. Thornton-Smith and his similarly occupied brother, Walter, appear to have been modestly born “Smith,” sons of civil servant Samuel Tomas Smith, but under the posher moniker “Thornton-Smith,” they both made fortunes catering to the tastes of England’s rich and privileged. Suggestive of estrangement from her husband, Ormond in 1967 would officially change her name by deed poll from Florence Ormond Thornton-Smith to Chita Florence Ormond Campbell.

Antiques play a significant role in Alice’s No Light Came On (1942) and Travelling Butcher (1944), a wartime novel which Kate Jackson at her Cross Examining Crime blog deemed “a thrilling read.” The author’s most comprehensive wartime novel was Ringed with Fire (1943), which native Englishman S. Morgan-Powell, the dean of Canadian drama critics, in the Montreal Star pronounced one of the “best spy stories the war has produced,” adding:

“Ringed with Fire” begins with mystery and exudes mystery from every chapter. Its clues are most ingeniously developed, and keep the reader guessing in all directions. For once there is a mystery which will, I think, mislead the most adroit and experienced of amateur sleuths. Some time ago there used to be a practice of sealing up the final section of mystery stores with the object of stirring up curiosity and developing the detective instinct among readers. If you sealed up the last forty-two pages of “Ringed with Fire” and then offered a prize of $250 to the person who guessed the mystery correctly, I think that money would be as safe as if you put it in victory bonds.

A few years later, on the back of the dust jacket to the American edition of Alice’s The Cockroach Sings (1946), which Random House, her new American publisher, less queasily titled With Bated Breath, readers learned a little about what the author had been up to during the late war and its recent aftermath: “I got used to oil lamps….and also to riding nine miles in a crowded bus once a week to do the shopping [at Bridport?]—if there was anything to buy. We thought it rather a lark then, but as a matter of fact we are still suffering from all sorts of shortages and restrictions.” Jamie Campbell, on the other hand, spent the war years in Santa Barbara, California. It is unclear whether he and Alice ever lived together again.

Alice remained domiciled for the remainder of her life in Dorset, although she returned to London in 1946, when she was inducted into the Detection Club. Six years earlier, in May 1940, English crime writer Anthony Gilbert, author of the popular Anthony Crook mysteries, had urged Alice’s nomination upon Dorothy L. Sayers, writing: “She would be an excellent member, would attend [meetings] and bring guests, is a professional writer who lives by her pen and is a charming woman and one of my best friends.” For her part, Sayers agreed that Alice “seems a charming person and should be a most excellent member.” Anticipating possible objection from Anthony Berkeley, something of a curmudgeon when it came to admitting any new members, Sayers strategized: “If Anthony Berkeley is opposed he is in Devon so we can do an end-run [around him].” Unfortunately, when it came to a vote of the membership committee, another obstacle loomed up in the form of Milward Kennedy, who apparently objected to Alice’s election. Although the nominee was supported by the more orthodox puzzlers Freeman Wills Crofts and John Rhode, her membership did not finally materialize until after the war.

Milward Kennedy’s view of Alice Campbell notwithstanding, Dorothy L. Sayers, back when she had reviewed crime fiction for the Sunday Times, had lauded Alice’s Desire to Kill, singling out “the soundness of the characterisation and the lively vigour of the writing,” which lifted the narrative out of “sheer melodrama.” Sayers pointed out that while the murderer is effectively revealed long before the end of the tale, there was genuine detection concerning the matter of alibis. Interestingly, around the time Anthony Gilbert was proposing Alice for membership in the Detection Club, there appeared a new Alice Campbell mystery, They Hunted a Fox, which is more of a formal murder puzzle than many other Campbell works, and set in nothing less than that sanctum sanctorum of Golden Age British detective novels, a country house party. A number of Alice’s mysteries from this period, which in England were all published by the Collins Crime Club, are shorter and more in the style and form of the true Golden Age detective novel.

Alice Campbell’s induction into the Detection Club may have been a moment of personal triumph for the author, but it was also something of a last hurrah.Alice Campbell’s induction into the Detection Club may have been a moment of personal triumph for the author, but it was also something of a last hurrah. After 1946 she published only three more crime novels, including the entertaining Tommy Rostetter-Inspector Headcorn sleuth mashup The Bloodstained Toy, before retiring in 1950. Now white-haired and grandmotherly in appearance, she lived out the remaining five years of her life quietly at a cottage near the small city of Bridport, Dorset, expiring “suddenly” on November 27, 1955, two days before her sixty-eighth birthday. Her brief death notice in the Daily Telegraph refers to her only as the “very dear mother of Lawrence, Chita and Robert.”

Alice’s sister Mary had passed away in Atlanta in 1951, while Jamie Campbell predeceased his wife by just under a year, dying by his own hand in 1954 at the age of sixty-five. Earlier in the year he had enjoyed a personal triumph when his play The Praying Mantis, billed as a “naughty comedy by James Lawrence Campbell,” scored hits at the Q Theatre in London and at the Dolphin Theatre in Brighton. In the latter venue, the play to great plaudits starred, in the role of the eponymous man-eater, a wickedly sultry, twenty-year-old Joan Collins, who would make an international sensation the next year in the film Land of the Pharaohs. In spite of this success Jamie near the end of the year checked into the Hotel Splendid in Cannes and imbibed poison, expiring around six in the morning on December 1. The American consulate sent copies of the report on Jamie’s death to Chita in Maida Vale, London and to Jamie’s brother Colonel George Campbell in Washington, D. C., though not to Alice. Jamie’s list of personal effects included hand grip—very old and worn, suitcase—very old and worn, navy blue pin stripe suit (old) and Westclox clock (broken). It is true that you cannot take it with you, but certainly Jamie appears to have had little with him to take. This was far from the Riviera romance that the publishers of Juggernaut had long ago promised. Perhaps the “humdrum of everyday life” had been too much with him.

As was the case with Jamie, Alice Campbell and her work fell into obscurity after her death, with not a single one of her novels having been reprinted in English for more than seven decades. Happily the ongoing revival of vintage English and American mystery fiction from the twentieth century is rectifying such cases of criminal neglect. It may well be true that it “is impossible not to be thrilled by Edgar Wallace,” as the great thriller writer’s publishers pronounced, but let us not forget that, as Maurice Richardson put it: “We can always do with Mrs. Alice Campbell.” Mystery fans will now have nineteen of them from which to choose—a veritable embarrassment of felonious riches, all from the hand of the other AC.