I was eighteen years old when I experienced The Shining for the first time. It was 2003. A North Carolina winter, my knuckle still hurting from a few days before, when a bunch of college freshman had used UNC’s campus picnic tables as makeshift sleds to get us down a massive hill near the underclassman dorms. We all still had all our limbs, most surprisingly, but my pointer finger swelled, a reminder of the sort of bad decisions one only makes in the cozy enclave of university life.

My best friend, Kate, had been assigned the movie for a freshman seminar course on film theory. We got the disc from the campus library, popped it in, and watched one of the greatest movies of all time on the glories of the 18” cube of a TV that she’d rescued from her parents’ garage. To complement the viewing experience, said TV was installed nearly at the ceiling, in a storage cabinet over Kate’s closet that happened to be the only available space for it.

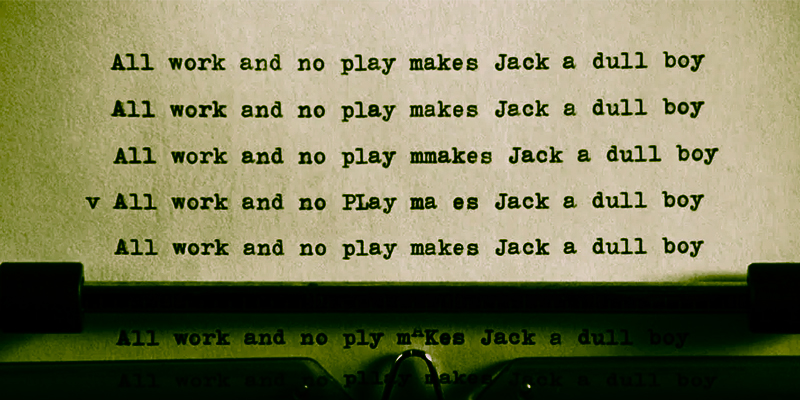

And yet, even with the worst viewing conditions imaginable, we were captivated. The brain-bending pattern of the rug, the way Danny rides his big wheel round and round hypnotically. The twin images of the young girls, always taunting. I might have been obsessed with words, majoring in journalism and minoring in English lit, and yet I still didn’t catch that the inverse of “redrum” was “murder” until it was revealed in the mirror. The sheer strangeness of Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation, the way furries will appear and disappear, how Shelley Duvall’s pitch-perfect Wendy holds a knife in a dangle akin to transporting a dirty diaper to the trash. Snow and isolation and cocktail-mixing ghosts and the way we get to watch, scene-by-scene, word-by-typewritten-word as Jack Nicholson’s Jack Torrance slowly, breathtakingly, loses his mind. Stephen King famously did not like the movie, of course, calling it “a maddening, perverse, and disappointing film,” but many of us see it as a masterpiece in its own right, as well as an invitation into the world of the book.

And what a world it is. It was at least a decade before I got around to actually reading The Shining, though I’d long been enamored by other King gems, from tightly woven narratives like Carrie and Misery to sweeping epics like The Stand and Salem’s Lot. Perhaps my deep love for the movie made me wait on the book, knowing it would be so different, knowing it might even change my read of the film. And once I read it, of course it did, but I loved it in its own way, so different than the movie, so wonderful on its own. To me, The Shining is a book, at its heart, of family dynamics, of addiction and alcoholism, of the horrors of not living up to what—and who—you want to be. And let’s not forget, Kubrick skipped the Overlook Hotel’s hedge animals coming to life to stalk the place’s inhabitants—fantastically creepy, a little goofy, and classic King.

But back to the characters. King creates a deeply flawed man in Jack Torrance, one whose demons get the best of him when he finds himself isolated and unable to finish his novel. And as a writer, it’s oddly compelling. Though we have this fantasy of escaping the real world and heading off to the country/woods/island/insert-Instagrammable-area-here to finish a novel in bursts of inspiration, the reality is often quite different. When a writer finds it hard to write, the isolation can act as even more pressure. The lack of distractions are theoretically good, but often overpowering. No, I haven’t personally filled pages upon pages with the words “all work and no play makes Leah a dull girl,” but sometimes, upon reading words dashed out in a true absence of inspiration and motivation, it feels like I might as well have. Writing is its own demon, one that follows us wherever we go.

My newest thriller, The Last Room on the Left , nods to The Shining—and to the relatable struggle of a writer desperate to finish her book. It opens with Kerry, an alcoholic herself, whose drinking has destroyed her marriage, her hopes of becoming a mother, her friendships, and potentially, her career. Though she had a short story go viral, leading to a big book deal and loads of press, she’s found herself completely unable to complete her novel. All the money she has in the world is tied up in the delivery of her book to her publisher, and so when she learns of a winter caretaker position at a revitalized roadside motel in the Catskill mountains, she jumps at the chance. Only problem is, once she arrives, her idyllic retreat is anything but. The room she’s supposed to be staying in is filled with another woman’s belongings, and on her first morning at the motel, she spots a frozen hand reaching out from the blanket of snow.

In The Last Room on the Left, there are essentially two Jack Torrances: Kerry, but another caretaker, too, one who was there the month before, one who has already come to her demise. I start all books with a question, and this one got my mind spinning: what if a book started at the end of The Shining, with a new caretaker arriving to find the previous caretaker already having perished, already out there in the snow?

Of course, The Last Room on the Left is far from a retelling. It draws inspiration from the isolated setting, the motel in the snow, the idea of creators just trying to create and the difficulties they have doing so, and, of course, the demons that haunt us, whether it’s alcoholism or something else. And for a Shining fan like myself, it was so fun to play with these ideas, to set myself up in a snowed-in motel, to write characters who stare at the blank page, desperate to create something, never knowing how.

After all, we’ve all been there, in one way or another. Wanting to be better than we are, struggling to do so. Needing to finish a book, seemingly forgetting every word in the English language. And I think it’s one of the reasons why The Shining still resonates and captivates all these years later—and will for many generations to come.

Or maybe it’s those hedge animals—they really are quite creepy.

***