Thirty years ago, in July of 1995, the city of Srebrenica fell to Serbian forces that had besieged that city for most of the Bosnian war. When it fell, Serbian soldiers entered the city and executed over eight thousand Muslim men and boys, some as young as ten-years old. I had been thirty-two years old when that headline would have flashed across my television screen, and at the time, it meant nothing to me. I was a young attorney building a law practice and starting a family. What should I care about a city halfway around the world that I’d never heard of before.

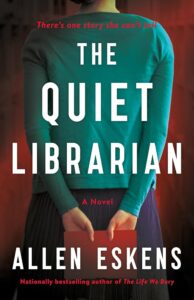

Flash forward to two years ago when I had an idea for a novel—The Quiet Librarian—that would tell the story of a middle-aged woman who had been forged in fire, a woman who came of age in a time and place that she kept hidden from the world around her. As the idea crystalized in my imagination, I went in search of that catalyst and came upon the war in Bosnia. My idea had been to use the war as a tragic event that shaped who she became, but as I waded into that part of history—the war, the atrocities, the human suffering—I came to realize that I could not write this character so thinly. And I could not write this character without help. So, I went in search of that help.

As a writer, I have often found myself in need of a little technical fine-tuning: the hierarchy of a prosecutor’s office, the layout of a crime lab, prison rules, and the like. And when faced with such challenges, I have reached out to people who work in those surroundings, and—like other authors—I have benefitted from the generosity of those people in the know. But writing about a Bosnian, Muslim, teenaged girl growing up during that horrendous war, well that was a task far more daunting than a simple phone call or a tour through a facility. Honestly, I almost scrapped the idea.

But I am fortunate to be both naïvely confident and a citizen of the great state of Minnesota. As it turns out, Minnesota has a large Bosnian community, having been at the forefront of helping Bosnian Muslims escape the carnage of the war during the 1990s. So, I sent an email to a Bosnian Center in Minneapolis and another to the University of Minnesota. A short time later, I had two people agree to help me understand what it had been like to live in that war-torn time and place. Meeting these two people not only changed my story but changed me in a profound way. While my goal in meeting with my two sources had been to create an authentic world and authentic characters, they gave me so much more than that.

Imagine sitting across from a woman as she casually tells of nearly being executed. How she and some of her Muslim classmates were taken from their school in Banja Luka and driven to a ravine to be executed. How her execution had been stopped because a Spanish journalist showed up and started asking questions. She told me of a night when the Serbian militia—men from her community, her neighbors who were now her enemies—decided over drinks that that night would be the night they would shoot up her house. Her family escaped because a Serbian friend warned them of the plot.

My other source came of age manning the trenches around the besieged city of Srebrenica. He talked of the ingenuity of a people who had been cut off from the world. He told of how they built generators from cement mixers which gave them enough electricity to run their refrigerators and a few lights. He told of the day that the helicopters came to the city to evacuate the generals. As he watched the men responsible for the defense of the city flee, he knew that the end was near. He and a friend hatched a plan to swim the river into Serbia and surrender. They had no way of knowing it, but that last minute plan saved his life. He was taken prisoner while others of his family and friends were among those put on the buses and driven into the woods to be executed.

I think what struck me the most in my conversations was the matter-of-fact way that they told their stories. There were no tears. No bragging. No intonation to suggest that they understood just how incredible their stories were. They told their truths in the same way that I might talk about building a treehouse with my father or getting stung by a bee when I was a child. I was in awe of them. Their stories instructed me regarding their culture and language. They helped me understand what it was like to walk in that world. And, in the end, I understood that what I wrote in my novel had to be more than just a backstory for a character. I needed to do my level best to write The Quiet Librarian so that my readers could walk in that world as well. There needed to be a reverence to my depiction, one that would honor those who survived that terrible war as well as those who did not.

This July will mark the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of Srebrenica, and as my character Hana Babić says in the novel:

“The world doesn’t care—it never cared. The Serbs slaughtered eight thousand men and boys in Srebrenica—took them into the woods and shot them. The men who pulled the triggers will never face justice.”

I had been one of the many who watched the war from afar, my attention pulled by the chores of daily life, my soul unaffected by their plight—but not any longer.

***