As a historical crime writer, there’s one trope I love more than almost anything, and that’s an old-timey thief with an elaborate scheme. If we had all day, I’d take you on a tour of all my favorite robbers and scoundrels, both real and fictional. Take Jeanne de la Motte, the French con artist who stole a diamond necklace worth about $17.5 million in today’s money by paying a sex worker to dress up as Marie Antoinette. Or the Gilded Age crime boss Marm Mandelbaum, who had a secret elevator hidden in her chimney to whisk away stolen goods when the police came to visit.

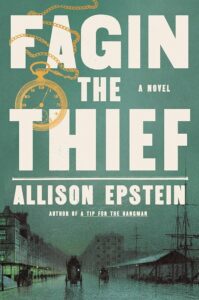

When it comes to old-timey thieves in fiction, though, there’s one book that looms large, and that’s Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens. We’re all familiar with the world of the Artful Dodger and his mysterious teacher Fagin, and after years of working on an Oliver Twist retelling, I deeply understand these characters’ lasting allure. There were plenty of reasons I sat down to write Fagin the Thief—digging under the surface of a two-dimensional villain, for example—but honestly, a core attraction was that writing about thieves is fun.

As someone who’s spent a disproportionate amount of time thinking about how and why someone would go about picking a pocket or two, I’ve developed some theories about why readers continue to fall in love with fictional robbers and thieves. Fundamentally, fiction about thieves blends the thrillingly unknown and the darkly recognizable in ways that can’t help but capture readers’ imagination.

Stories about thieves are relatable, at least in a way that crime fiction about serial killers or unsolved murders might not be. The classic trope of the thief with a heart of gold is seductive because it takes the honorable values so many of us aspire to and flips them through the looking-glass into deviance. Equity, justice, and an exciting train robbery? Small wonder we’re a fan.

But the less-savory type of thief can be much more interesting. A fictional thief’s motivations are frequently dark, but if we’re honest, they aren’t unfamiliar. Survival, jealousy, resentment, exhaustion. A sense that if the rich can exploit others, surely there’s nothing wrong with exploiting them a little in return. And the desire for something nicer than we’re used to: something sparkling to hold up to the light, which we would appreciate, we’re sure, in a way its rightful owner never would.

If it sounds like I’m about to say something cringeworthy like “no ethical consumption under late-stage capitalism,” well, there’s a reason Dickens wrote his original novel as equal parts entertainment and social commentary. There is no property crime without ownership, and in 2025 as in 1825, there’s no ownership without exploitation. Under a fair system, thieving wouldn’t come with the same sense of punching up to spite the rich.

To me, this makes fiction about thieves and other petty criminals more socially subversive than crime fiction about murder. In a murder mystery, we’re usually rooting for the killer to get caught; in fiction about thieves, we’re rooting for the criminal to get away with it.

This same sense of relatability makes crime novels about thieves ideal for characters with rich, complicated, and familiar interior lives. Novels centering violent crime or murder face a particular structural challenge here: it’s difficult to write a character who has the emotional response most of us would have to a murder and engages in the kind of high-stakes plot we expect from a crime thriller. If someone I love was murdered, I doubt I’d be teaming up with the local cops to search for clues. I’d be having twice-weekly sessions with my therapist and bursting into tears while doing basic tasks. The resulting book might be an interesting slow-paced reflection on grief, but few would call it a crime thriller.

But a story about a theft or heist isn’t quite so grim—which, paradoxically, can let a book delve into even darker places. Because the stakes of pickpocketing aren’t inherently life or death, a fictional thief doesn’t need to be grimly resilient or hell-bent on revenge to soldier through the horror of the inciting incident and keep the plot moving. They can be cowardly, selfish, prideful, jealous: any number of small, unheroic traits we can begrudgingly recognize in ourselves. And what happens to these imperfect characters under incredible pressure? What kind of pain, struggle, betrayal, horror, and growth comes out of that crucible? I can’t stop reading pages to find out.

Books about thieves can start off with a crime that’s exciting and even attractive, then slow-simmer into the mess of guilt and grief and terror and anger that gives a story its staying power. Every twist and complication can hit with the full emotional weight we would expect in our own daily lives, while maintaining the propulsive energy that keeps these stories thrilling.

And if done well, every page you turn can feel like looking in a mirror.

***