In 1929-30 Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest, along with the author’s two other novels, The Dain Curse and The Maltese Falcon, which quickly followed it, struck the landscape of classic mystery like a fistful of dynamite. “Hammett is the man who set out for himself the task of raising the detective story to literature,” one syndicated newspaper reviewer breathlessly pronounced of the new author (just like English author Dorothy L. Sayers was The Woman). Hammett’s Red Harvest, the reviewer noted, had been “hailed by many as a revelation of what the detective story could be in the hands of a master.” In contrast with all those cliched American and English mysteries about millionaires murdered in the libraries of their country mansions, the raw and racy Red Harvest was “original, unique, lively and real.”

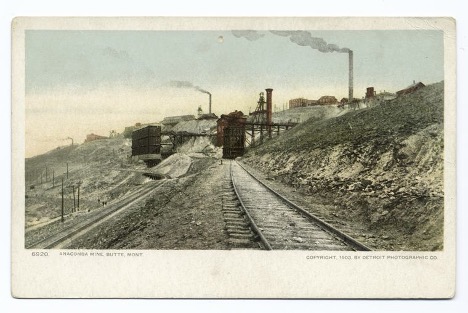

Today Red Harvest is routinely said to have been inspired by Hammett’s experiences as an operative of the Pinkerton Detective Agency stationed in Montana in the years shortly before and after America’s participation in World War One. People who should know assure us that locations in Personville, aka “Poisonville,” the fictional setting of the novel, correspond with real places in the Butte-Anaconda-Walkerville metropolitan area of Montana. Specific Montana events which are said to have inspired Red Harvest are the lynching of Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) labor organizer Frank Little in 1917 and the 1920 Anaconda Road Massacre, where guards working for the Anaconda Copper Mining Company fired on a picket line of striking miners, killing one and injuring nearly a score of others.

Dashiell Hammett’s companion, playwright Lillian Hellman, later claimed of Hammett that as a Pinkerton Op he had been in Butte in 1917 and actually had been offered money personally to kill Frank Little. Dramatic as this story is, Lillian Hellman, was, not to mince words, a literary fabulist with a predilection toward touching up truth in her accounts in order to make better copy, while Hammett himself was known to tell a tall tale about his exploits on more than one occasion. His daughter Jo also places Hammett in Montana, this time in 1920, but the sad truth is that there is a paucity of primary material about Hammett’s early life (including Pinkerton Detective Agency records), just as there is in the case of that other great hard-boiled detective writer, Raymond Chandler. Hammett’s wife, Josephine Dolan, offers another connection to Montana, however, her family having come from Anaconda.

Whatever the truth which lies buried in Hammett’s biography, internal evidence from Red Harvest itself certainly indicates that the author had Butte in mind when he fashioned Personville. Aside from the similarity to the name of Walkerville, now a Butte suburb, there is a passage where the Continental Op gives some of the sordid history of Personville and its boss, Elihu Wilsson, president of the Personville Mining Corporation and ruthlessly scheming capitalist pirate:

Back in the war days the I. W. W.—in full bloom then throughout the West—had lined up the Personville Mining Corporation’s help…. Old Elihu gave them what he had to give them, and bided his time.

In 1921, it came. Business was rotten. Old Elihu didn’t care whether he shut down for a while or not. He tore up the agreements he had made with his men and began kicking them back into their prewar circumstances.

[…]

The strike lasted eight months. Both sides bled plenty. The wobblies had to do their own bleeding. Old Elihu hired gunmen, strike-breakers, national guardsmen and even parts of the regular army, to do his. When the last skull had been cracked, the last rib kicked in, organized labor in Personville was a used firecracker.

It is not hard to discern Butte in these vivid passages.

The Op goes on to describe what happened in Personville after ruthless old Elihu broke the strike: “He won the strike, but he lost his hold on the city and the state. To beat the miners he had to let his hired thugs run wild. When the fight was over he couldn’t get rid of them.” So when the Op arrives in Personville—let us just call it by its apt nickname, Poisonville—he finds it is run by those same thugs, who have set themselves up in charge as racketeers and bootleggers. The Op has come at the request of crusading newspaper publisher Donald Wilsson—the idealistic son, only lately returned from France, of Elihu. But Donald is found shot dead in a street before the Op ever lays eyes on him.

The Op soon solves the matter of Donald’s murder, but he has to evade attempts on his own life instigated by the wicked Powers that Be in the city. This provokes him to vow to clean up Poisonville himself and he sets about it most sneakily and effectively, like a modern-day Machiavelli, with Elihu sitting on the sidelines, though he gets help of a sort from a mercurial and mercenary woman of rather easy virtue, Dinah Brand. An orgy of violence in Poisonville follows, as the Op sets thug against thug in a grim gang turf war. He manages to solve another murder, this one a murder from the past that comes complete with an Ellery Queen-ish sort of clue. Before it is all over, the Op will be accused of murder himself, making yet another mystery he must solve. There is a lot of murderous bang for your crime buck in Red Harvest.

Compared to an English mystery from the period, even an Edgar Wallace or Sapper shocker, the violence level of Red Harvest is extraordinary. In the book there is a chapter titled “The Seventeenth Murder,” which gives you an idea of what I mean; and there are yet more slaughters after that. Decadent Movement gay writer, art photographer and Halem Renaissance patron Carl Van Vechten, a man not easily shocked, glibly pronounced Red Harvest “swell, a bloody humoresque,” which is one way of describing it. Of course the United States of a century ago was a vastly more violent country than merrie old England (setting certain topical horrors in Ireland aside). And this is what got me thinking that Red Harvest may well have had other sources of inspiration in recent American history besides those which tragically took place in Butte, Montana over 1917-20.

bullet holes in a window at the treasurer’s office at the Douglas County Courthouse in Omaha, Nebraska after the 1919 race riot

bullet holes in a window at the treasurer’s office at the Douglas County Courthouse in Omaha, Nebraska after the 1919 race riot

Red Harvest’s contemporary reviewers, invariably noting that the novel’s author was a former Pinkerton operative (Hammett’s publisher Knopf played this point up in publicity for all it was worth), frequently speculated about the real-life inspiration for the novel. In San Francisco, the primary setting of Hammett’s Op tales, the Examiner asserted that Personville was based on a real town that Hammett himself had once cleaned up “much the same as he describes the process in his book…. It lies not too far away from here so that many local people will probably recognize it, yet far enough away to make its identification difficult for those who do not really know the town.” Was the Examiner talking about Walkerville/Butte, which is located over one thousand miles away from San Francisco, or some closer locale in northern California? The distance seems rather great to me for Butte to be the place about which the Examiner was speculating, but then I am not a Californian.

The thing which soon becomes evident is that there were ever so many candidates in the United States for the real life “Poisonville.” Midwestern reviewers of Red Harvest felt certain that, the view of the San Francico Examiner notwithstanding, Hammett’s sources of inspiration for the novel lay in their region rather than the Far West. In the April 6, 1929 issue of the Sterling Illinois Daily Gazette, the compiler of “Book Notes from Public Library” remarked of Red Harvest: “Somebody said ‘It reads like the latest news from Chicago.’” The bloody gangland St. Valentine’s Day Massacre had taken place in the nation’s mob capital just seven weeks earlier and was still ricocheting around the nation’s newspapers and radio airwaves.

Other reviewers offered more original candidates for Poisonville. At the Cincinnati Post the reviewer knowingly pronounced that what had inspired Hammett in his depiction in Red Harvest of the murder of fictional crusading anti-crime newspaper editor Donald Wilsson was the real-life murder three years earlier in the city of Canton, Ohio of crusading anti-crime newspaper editor Donald Mellett. For his part the reviewer in the Greensboro North Carolina Daily Record detected similarity between the events depicted in Red Harvest and the so-called “Herrin Massacre” that in 1923 had taken place at the town of Herrin, Illinois, during which striking union coal miners, ghoulishly cheered on by hundreds of townspeople, systematically slaughtered the local mine superintendent and his assistant, along with seventeen strikebreakers and mine guards. That is one dreadful incident that traditionally has not been taught in the history books, perhaps because it puts the labor movement in a rather shocking bad light.

Herrin Massacre (1939), Paul Cadmus

Herrin Massacre (1939), Paul Cadmus

The intensity of the mass violence which afflicted the United States in the years following World War One is truly remarkable and offers a corrective to those who with willful naiveté like to talk of the time before the social upheavals of the Sixties as the “good old days.” In addition to repeated outbreaks of racial violence, the broader period from Reconstruction up through the Depression saw as well the great struggle for dominance in the western world between capital and labor, of which the horrid events at Butte and Herrin referenced were but a couple of beastly manifestations. Gangsterism also ran amok in America, as the assassination of Don Mellett revealed. All of these events may well have gone into Red Harvest in one form another. But there was yet more.

Douglas County Courthouse on fire during the Omaha riot of 1919

Douglas County Courthouse on fire during the Omaha riot of 1919

Douglas County Courthouse on fire during the Omaha riot of 1919

The year 2020 marked the ninety-ninth anniversary of the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 and with his perverse genius real estate mogul and all-round conman Donald Trump, then in the final year of his first term as president, scheduled a MAGA rally to take place in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The Tulsa Race Riot was indeed horrific, but I am more interested for my purposes here in a race riot which took place two years earlier in Omaha, Nebraska, during the so-called “Red Summer” of 1919, because I see in it a particularly strong possibility of a connection to Red Harvest. (Note the similarity between the terms Red Harvest and Red Summer.)

As was so often the case with American race riots, violence erupted in Omaha after a white woman claimed she had been sexually assaulted by a Black man, a situation which always could be counted upon to set a savage white mob up in arms. On September 26, 1919, the newspaper the Omaha Bee told the story—or told a story, if you will—under the headline “Black Beast First Stick-Up Couple.” The Bee dubbed the affair the “most daring attack on a white woman ever perpetrated in Omaha.” It expounded as follows: “Pretty little Agnes Loebeck….was assaulted by an unidentified negro at twelve o’clock last night, while she was returning to her home in company with Millard Hoffman, a cripple.”

Alleged victim Agnes Loeback

Alleged victim Agnes Loeback

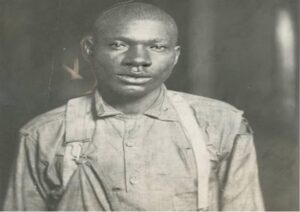

Pretty little Agnes and poor crippled Millard identified a forty-year-old Black meat packer, Will Brown, as the assailant, despite the fact that Brown badly suffered from rheumatism. In the face of a large angry crowd gathering in the city, local police managed to escort Will Brown to the courthouse, but then all hell broke loose in Omaha. By the evening of September 28, a mob of some five to fifteen thousand people had converged upon the courthouse, trapping inside prisoners and local government officials and personnel alike. What followed the website nebraskastudies.org describes: “By 8:00 p. m. the mob had begun firing on the courthouse with guns they looted from nearby stores. In that exchange of gunfire, one 16-year-old leader of the mob and a 34-year-old businessman a block away were killed. By 8:30 the mob had set fire to the building and prevented the firefighters from extinguishing the flames.”

When the Omaha mayor came out of the courthouse to try to talk down the frenzied mob, he was violently knocked down and, next thing he knew, he found himself hanging from a rope before he passed out. Fortunately for the mayor someone intervened to save his life. Will Brown was not so lucky. To save themselves from incineration, the desperate white occupants of the burning courthouse agreed to turn over the hapless black man to the mob. Brown was beaten unconscious, then hanged from a lamppost till he was dead. His body was then riddled with bullets and set on fire. Later his charred remains were dragged around town from a car. Beaming white men, so very proud of themselves for having avenged a dubious white woman’s sullied virtue, posed for pictures with the corpse. Pieces of the rope were sold as souvenirs.

A witness to the lynching was future actor Henry Fonda, then just a fourteen-year-old boy. Fonda’s father owned a printing shop across the street from the courthouse and young Henry watched the whole thing from the second floor. “It was the most horrendous thing I’d ever seen,” he later recalled. “We locked the plant, went downstairs and drove home in silence…. All I could think of was that young man dangling at the end of a rope.” It was Spencer Tracy, not Henry Fonda, who starred in the 1936 Fritz Lang film Fury, which depicts scenes reminiscent of the Omaha riot (though the victim, naturally, is white); but in truth similar stories could have come from any number of other American cities, there having been so many of these grotesque affairs which took place in the United States, and certainly not just in the South.

Will brown, murdered in the 1919 Omaha riot

Will brown, murdered in the 1919 Omaha riot

The seemingly over-the-top violence in Red Harvest, including bombing, Tommy Gun battles and the dynamiting of the city jail, truthfully comes straight out of contemporary American newspapers. What especially reminds me of Omaha in are a couple of additional things, however. First, there is the Machiavellian way the Op sets the thugs against each other. It has been credibly alleged that Omaha race riot resulted from Omaha machine politics, which makes the whole event even more hideous.

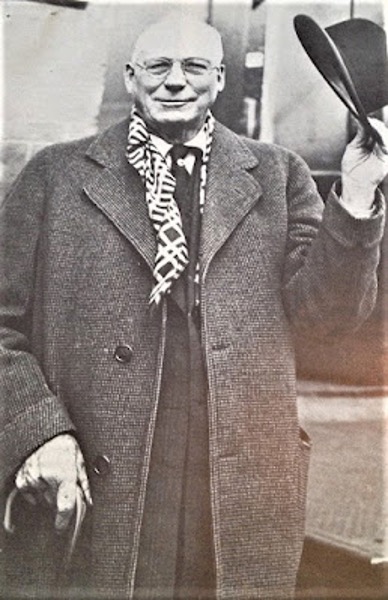

Omaha’s longtime political boss was a man named Tom Dennison. In his ruthless cynicism Dennison, aka the “Old Grey Wolf,” was like a character out of a Hammett novel—or rather the characters in Hammett novels were like Tom Dennison and his minions. “There are so many laws that people are either lawbreakers or hypocrites,” the boss once pronounced. “For my part, I hate a damn hypocrite.” As boss of Omaha for three decades, Dennison ran the city’s myriad crime rings, which included the trifecta of prostitution, gambling and bootlegging. Dennison’s puppet mayor, Jim Dahlman, aka “Cowboy Jim,” was in office from 1906 to 1930, doing Dennison’s bidding, with the exception of one term, from 1918-1920, when a reform Republican candidate, Edward P. Smith, was in office. Remember the mayor the race rioting mob tried to lynch outside the Omaha courthouse, who barely escaped with his life? That was Edward P. Smith.

Mayor Smith had been elected vowing to clean up vice and ban booze, which of course was utter anathema to Dennison, who responded, it is believed, by launching a covert campaign to undermine the new mayor. This underhanded campaign allegedly included having some of his men assault white women in blackface, in order to escalate racial tensions in the city. The demagogic Omaha Bee, one of the city’s two leading newspapers, accused Mayor Smith of negligently allowing a black crime wave to take place on his watch, imperiling the virtue of white women throughout the city.

Agnes Loebeck’s boyfriend, the “cripple” Millard Hoffman, is said to have worked for Dennison and been an active leader of the Omaha lynch mob. It was also said that pretty little Agnes’ womanly virtue was a touch shopworn and that she carried a personal grudge against Will Brown. Whatever the truth of these matters, it is all incredibly seedy and disgusting and reminiscent of the ruthless political maneuvers in Red Harvest and another Hammett novel, The Glass Key (1931). Will Brown, it appears, was just a black pawn on Boss Dennison’s chessboard, a piece the Old Grey Wolf was only too willing to sacrifice to achieve his goal of removing Omaha’s reform mayor.

Boss Dennison

Boss Dennison

When Raymond Chandler wrote that Dashiell Hammett took crime out of the Venetian vase and dropped it in the alley, he was not kidding. But with Red Harvest it would be more accurate to say that Hammett loaded that vase with nitroglycerin and hurled it with maximum impact at the weighty edifice of staid and proper detective fiction. For people who wanted to read something which viscerally represented the all-too-real cruelty and carnage that was occurring all over America (not to mention much of the rest of the world), Red Harvest really fit the bloody bill.

Postscript

Although a Republican newspaper, the Omaha Bee in 1919 had long had an alliance with Boss Tom Dennison, a Democrat. The Bee’s anti-Progressive editor, Victor Rosewater, had inherited the job from his immigrant Jewish father, who founded the paper in 1906. Two days after Will Brown’s lynching, the city’s leading local paper, the Omaha World Herald, published an editorial which memorably characterized the lynch mob and its actions as “wholly vile, wholly evil and malignantly dangerous.” The World Herald editor, Harvey Newbranch, won a Pulitzer Prize that year for this anti-lynching editorial. Over at the banefully busy Bee, however, Victor Rosewater kept up his racial agitation, assisting rioters to evade the mills of justice. He went on the attack against the grand jury investigation into the manifold crimes committed by the lynch mob, going after the police department as a whole and specific police officers who testified against rioters. Rosewater in the event was charged with obstruction of justice and later found guilty of contempt of court and fined a thousand dollars. His tactics worked, however, for although scores of arrests of rioters were made, no one was ever convicted of a crime and the reform mayor was defeated when he ran for reelection in 1920. In an outcome like something out of a Roman Polanski film (“Forget it, Jake, it’s Omaha”), Tom Dennison was back in charge, with Victor Rosewater’s help.

Having done his dirty work, Rosewater sold the Bee in 1920 and moved to Philadelphia, the City of Brotherly Love. In the last twenty years of his life he authored several books, including a history of the Liberty Bell. He was celebrated as one of the nation’s prominent Jewish Americans and received a long and laudatory notice in the New York Times when he died at the age of sixty-nine in 1940. The role he and his newspaper played in the Omaha race riot and lynching went unmentioned in the pious account of a noble life well-lived. It was an outcome the dark irony of which should have appealed to the author in Hammett, a man who had seen it all.

The corruption of urban political machines and the role of newspapers in that corruption is a focus of both Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest (1929) and The Glass Key (1931), so it seems quite a coincidence that in 1934 Hammett would have accidentally latched onto a name like Victor Rosewater as a shady character in his novel The Thin Man. In the film version of The Thin Man, the name of Victor Rosewater is changed to Victor Rosebury, suggesting that the filmmakers wanted to avoid the possibility of a legal wrangle, the real Rosewater being still alive. (Or perhaps they were just WASP-washing an “ethnic” character.) One wonders how the name got by Hammett’s publishers at Knopf. (In the novel the name of pianist, composer and wit Oscar Levant is changed to Levi Oscant.) This account offers further evidence that when writing his crime fiction Dashiell Hammett really had paid attention to, and thought a great deal about, the mass violence which afflicted Omaha and other American cities in the harried, hateful days of 1919-21. Certainly the civil liberties of Black Americans was a matter that would, to the author’s own personal sacrifice and his lasting credit, preoccupy him over the remaining years of his life.