In the 1970s, the streets of Harlem were no joke. Although you could still hear James Brown’s funk at the Apollo, catch a flick at the Victoria, buy 45s at Bobby Robinson’s record shop, party with mack daddy players at the Shalimar and eat chicken & waffles at Wells, the community had also become saturated with grime, crime and heroin. As a child of that era as well as that area, I clearly recall the notorious living dead junkies standing in the shadows of tenement doorways, nodding on street corners and plotting on the next person they were going to rob to pay for their fix.

Some of those lost souls were disillusioned people who rarely left the hood while many others were Vietnam vets who came back to America scarred and hooked on “that stuff,” as my grandmother referred to the drug. Most junkies weren’t great at holding down jobs, and their random crimes contributed to the rotting of the Big Apple. A few years later films Panic in Needle Park, The French Connection, Super Fly and Gordon’s War and documented the city’s dope danger and brutal bleakness.

In 1971, not far from the real Needle Park, saxophonist King Curtis, who was once friends with gangster Bumpy Johnson and played gigs at Small’s Paradise on 125th Street, was killed by junkies who’d been shooting dope in front of a West 86th Street residence he owned. Meanwhile, further uptown, on 116th between 7th and 8th Avenues, hopheads were losing their minds over some new shit called Blue Magic. Purer than most of the other product on those uptown streets, Blue Magic was a trademark that belonged to drug kingpin Frank Lucas. Formerly the right-hand man and driver for Bumpy Johnson, the original godfather of Harlem, Lucas claimed he shipped smack directly from Asia’s Golden Triangle in false bottom caskets.

“It’s funny, I don’t even know where the name Blue Magic came from,” Lucas said in his 2010 autobiography Original Gangster, co-written with journalist Aliya S. King. “I might have made it up, but I don’t know for sure.” Though some of Lucas’ alleged feats and boasts seemed unbelievable, his stories were always thrilling, sometimes sad, but with a voice that came across like your drunken uncle telling ghetto tales at some Sugar Hill saloon.

A country boy from La Grange, North Carolina, Lucas arrived in Harlem in 1944 when he was 14 with nothing except his nerves, balls and need to survive. He slept with bums in the basements of buildings until he started making loot as a mugger, dope boy and stick-up kid before he was “adopted” by Bumpy one night in a pool hall. He’d impressed Bumpy with his pool-table skill when he beat a psycho killer street dude named Icepick Red.

Lucas started out as Johnson’s driver as the older man taught him “the game.” Bumpy has been depicted in more than a few films and television shows including Shaft (Moses Gunn), The Cotton Club/Hoodlum (both films, Laurence Fishburne) and Godfather of Harlem (Forest Whitaker). Though legendary in the underworld, according to Lucas his boss wanted no part of the drug business. After Bumpy’s sudden death in 1968 while sitting at his usual table at Wells, Lucas branched out on his own and became a big shot. Over the next seven years he grew from thug to self-proclaimed entrepreneur (he refused to refer to himself as a drug dealer) racking in millions a year.

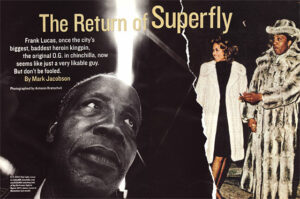

Then, on January 28, 1975, he and his wife were busted at their New Jersey home. For the next 20 years Lucas would be in and out of prison as he tried to figure out how to survive in a new world where he was the boss. Some people claimed that Lucas did a lot of snitching in his time, the man himself insisted he never dropped dime on nobody except crooked cops. Lucas’ underworld life and times went mainstream with the riveting New York magazine story The Return of Superfly (2000) by writer Mark Jacobson. “(With) Blue Magic, you could get 10 percent purity. Any other, if you got 5 percent, you were doing good. We put it out there at four in the afternoon, when the cops changed shifts. That gave you a couple of hours before those lazy bastards got down there. My buyers, though, you could set your watch by them. By four o’clock, we had enough niggers in the street to make a Tarzan movie. They had to reroute the bus on Eighth Avenue…by nine o’clock, I ain’t got a fucking gram. Everything is gone. Sold…and I got myself a million dollars.”

The other king of the drug game above 110th Street was Nicky Barnes, who Lucas disses in the original article. Yet, while Lucas tries to convince the world that he was larger than life, it was actually Nicky Barnes who had the bigger name and fame on the streets of Harlem. Both men would be taken down by their flamboyance. Jacobson did a hell of a job bringing both his subject and the era to life, and seven years after the story was published it was (finally) adapted into the Denzel Washington film American Gangster directed by Ridley Scott.

The film was originally supposed to be made by Training Day auteur Antoine Fuqua, who I still believe would’ve been a better choice, but he was fired by the studio supposedly due to rising budgetary problems. Ridley’s version wasn’t bad, it just felt cold to me. Still, the cast that included Russell Crowe, Cuba Gooding Jr. (as cool Nicky Barnes) and Ruby Dee in her last role. For the music, Denzel Washington campaigned producer Brian Grazer to get native New Yorker, former corner boy and brilliant rapper Jay-Z to do the soundtrack.

The producers decided to use period music (Bobby Womack, The Staple Singers) as well as vintage sounding Anthony Hamilton and instrumentals by former Bomb Squad producer Hank Shocklee. However, never one to be deterred once he’s set his mind to something, Jay-Z decided to make an American Gangster album featuring production by Diddy, The Neptunes and Just Blaze was, at least to me, one of the best albums of his career.

Jay-Z, who will be inducted in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame this year, came into the “rap game” already a businessman with his own Roc-A-Fella Records changing the rules of ownership from day one. In 1997, I voted Jay’s debut Reasonable Doubt as Album of the Year in the pages of NY Press as well as writing a cover story on him for The Source. After spending a few days with him in the Bahamas, where we played blackjack together and puffed cigars, we returned to the city where he took me to Marcy, his spot on State Street and a dinner in Brooklyn Heights.

Jay was a smart, witty interview, and ten years later, even more so. In September, 2007, when I was writing for Stop Smiling magazine, I was invited to Roc the Mic studios by a Def Jam publicist for a private audience with Jay. He played me various completed tracks and talked in-depth about the project as well as his own misadventures in the drug game on the streets of NYC during the crack years that exploded in 1980s. “I took elements of the film, but tried to make it a bit more soulful,” Jay said. “The album is called American Gangster, but it has nothing to do with me running out of the house with two Uzis just blasting. I’m trying to deal with inner conflicts and battles.”

Although the Neptunes produced “Blue Magic” was the first single released, some of the album’s best tracks were constructed by Harlem’s own P. Diddy and his Hitmen crew including the hypnotic “Roc Boys (And the Winner Is)…” The track, one of my all-time Jay-Z favorite, was a cool party song as well as an autobiographical gaze at his own fast times on the street. “In the 1980s, being a gangster changed from a gentlemen’s game to a vicious young man’s game,” Jay explained. “There were no more rules—-teenagers had automatic weapons, the money was bigger and it just got out of control. There was no hiding it, no shame. There wasn’t even shame from the addicts. People were just standing around smoking crack outside like it was normal; that’s not normal. Some people in those communities just lost control.”

Working with Puffy, who has made a career out of romanticizing slick uptown gangsterism with his Bad Boy artist The Notorious B.I.G and Mase, was a perfect pairing. “Puff’s father (Melvin Combs, a low-level Harlem gangster who was murdered in 1972) was one of those dudes, so he got it honestly,” Jay-Z said. In fact, Melvin Combs, though not shown in the film, appears in the book. “Puff had been inviting me to the studio. I would be like, ‘If you got some Biggie type tracks, let me know.’ A few days after American Gangster was put into place, I went to hear some music; he and his team the Hitmen used all these soul food samples that were perfect for the period. Puff put the foundation of this album together.”

From beginning of Jay-Z’s debut Reasonable Doubt, which has a reenactment of the classic shootout scene from Carlito’s Way (“I’m reloaded…you gonna die big time”), it was obvious that gangster films were an influence on his cinematic style, content and storytelling. “I like gangster movies that show a range of emotions and vulnerability, not just action,” he explained. “Action is cool, but I like the texture and complexity of human beings. Godfather was the powerful head of a crime family, but you also see the compassion he has for his own blood. I love Godfather, but Godfather II is my favorite film of all time. Other films like Scarface, kids of my generation watched that over and over, some reciting the dialogue back. ‘Never get high on your own supply.’ Biggie said that on ‘Ten Crack Commandments.’ We took so much from those films. We wore them like clothes; we took pieces of them and put them on.”

While American Gangster showed Lucas as a devoted family man, he was also cold-blooded when it came to the destruction he was calling.

“In the movie (American Gangster), you see one scene where Frank is having dinner with his family and the next there are junkies falling all over the place,” Jay said. “One person might say, ‘I’m never going to do that to my people.’ Somebody else is going to be enamored with the bad things. If people have bad intentions in them, that’s what they do. In (Iceberg Slim’s 1969 classic) Pimp, some brothers who read it were thrilled with the fur coats, but they seemed to miss the part where he got shot-up or thrown in jail. The trip through the American Gangster album is dangerous—there are pitfalls and constant obstacles in the way.”

Still, one must wonder how gangsters like Al Capone, John Gotti and Frank Matthews capture our imaginations so much in the first place. “You know, there’s this hope that we can make it out of bad situations and become important,” Jay explained, “maybe live like rock stars. For many of us, society is oppressive—our schools are the worst, our roads are the worst. So, when somebody goes against that oppression, it’s impressive.”

Although Jay-Z has always been open about his own Brooklyn vice days in Marcy Projects, there are those who try to still try to shame him about his past. “I’m not condoning it, but everyone chooses their path,” Jay replied. “I make no apologies for the path that I chose. People think that kids who become drug dealers are monsters. They’re not monsters, they’re just regular kids who are pushed up against the odds; and the odds keep putting the lights out on their hopes. Look at the staggering number of Black and Latino youth who go to prison. That alone has to do something to your self-esteem, and that affects the entire community.”

“Kids understand the dangers of dealing drugs or being a gangster,” he continued, “but often it’s better than what they already have in their lives. In their minds, even danger is better than that. It’s very sad, and what’s sadder is there are some people in the hood who are very intelligent, but they have no outlets. It kind of makes you think that keeping poor people down was done by design; these areas haven’t gotten so out of hand by mistake.”

So what made Jay different than the dudes he once hustled with? “I guess because I was able to look towards the future,” Jay said. “Most people wake-up and just deal with today. I realized that I couldn’t keep doing the same things and not have something bad happen to me. I knew I was going to go to jail or I was going to die. If you keep rolling the dice for ten years, it’s bound to catch-up to you. I also realized that I had a remarkable talent and I was letting it go to waste. I didn’t have one foot in rap and the other in the drug game, I literally changed my life. You just can’t hold on to the branches like Donkey Kong.”

We both laughed. “What did your boys say when you decided to leave?”

“Back in ’96 when I released Reasonable Doubt, rappers weren’t on the Forbes list and things like that. I had guys on the street laughing at me. They said things like, ‘You’re taking a demotion.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, well at least I have a career.’ At that time, a rapper’s shelf life wasn’t that long. Those same guys just laughed and said, ‘Whatever. We’ll see you back on the corner after two albums.’”

At the time of our interview, Jay-Z was already a successful businessman who had little problem transitioning to the boardroom, but he soon discovered that the corporate world played by different rules. “It’s worse in business, because there is no fear of retribution,” he said. “If somebody fucks me on a deal, then later I’ll fuck them on a deal. But, other than that, nothing happens. On the streets, you have to have integrity or you won’t be there long. You can’t give your word and then do the opposite. In business, people just run all over each other; it’s unpoliced.” Still, at least going the corporate route can keep the Feds from kicking down your door at dawn or rivals blasting you away.

Three years after American Gangster, Lucas and King’s book Original Gangster book was published. I liked this straight-up account more than the film. Having known King since her days at The Source, the woman knows how to tell a story. While the movie portrayed Lucas as one of them “gentleman gangsters,” he was far from it. Denzel Washington gave him a level of class and swag that the real-life Lucas lacked.

As a true-crime aficionado, I’m glad his story was told. In the end, Frank Lucas lived a long life. A part of me believes it was because, as my grandma used to say, “The Lord didn’t want him and the devil didn’t want him either.” On May 30, 2019, one or the other decided it was finally time. He was 88.