The first time I read American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis, I abandoned it two-thirds finished. Listen, I was a freshman in college. Very fresh into college, actually—it was orientation week. With a few empty days of freedom before classes started, on my first week away from home, I decided to pick up a book about a finance bro turned remorseless murderer. Up until that point, I’d hardly been able to tolerate even fairly benign scary movies, but dark stories always fascinated me. This one was far more gruesome and horrifying than anything I’d read before—I ended up hiding the book in a drawer and sleeping on the floor of a dorm-mate I barely knew because my roommate was out of town and I was afraid to be alone.

Just over a decade later, while revising my latest novel, youthjuice, I found myself thinking about American Psycho again. I was trying to write a horror story set against a glamorous backdrop—a beauty and wellness company in New York City’s SoHo neighborhood—dealing with consumerism and the pursuit of physical perfection. I was searching for that perfect balance of sharp social satire and stomach-turning body horror. Naturally, I found myself thinking about the book I’d abandoned as a younger reader and writer.

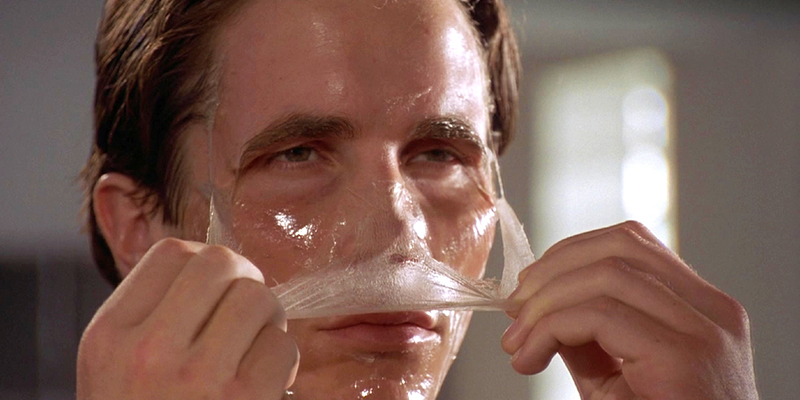

Revisiting American Psycho, I saw just how funny it was. Better yet, that humor reinforces and amplifies the horror—it’s one thing to depict a cunning murderer, it’s another take us through his inner monologues about Huey Lewis & the News and his extensive morning routine (a precursor to the popular “Get Ready with Me”–style videos that overpopulate YouTube) in between slaughters. Patrick Bateman is a monster, but a strangely relatable one who deals with petty jealousies and boring dinners with colleagues. On my second (and first full) read-through of Ellis’ third novel, I finally understood why it became a modern classic.

Two common complaints pop up in reader reviews of American Psycho—some say it’s too banal, too focused on the dull details of what designer suit so-and-so is wearing or what everyone is eating at Texarkana; others object that it’s gratuitous, the violence too over-the-top. However, both are equally necessary: the book wouldn’t work if either the banality or the violence was dialed down. In Bateman’s endless recitation of details, you can feel the attempts to stifle his true nature and murderous impulses under a torrent of what he views as normality. This lends tremendous comic power to the scenes when he slips up and reveals himself in public. Consider the famous moment when a woman at a club asks what he does for work and he says, “Murders and executions, mostly.” The joke, of course, is that she mishears him as saying “Mergers and acquisitions” because it’s too loud and—illustrative of one of the book’s central themes—she’s not really listening, anyway. I have never found another novel that blends humor and brutality quite so effectively, without minimizing one or the other. The jokes are almost as chilling as the deaths for what they say about the soullessness of ’80s New York yuppie culture.

In the decades since, it’s only become clearer how the destructive systems Ellis satirized have metastasized. I never worked on Wall Street, but as a beauty editor in my early– to mid-twenties, I spent time in a similarly status-obsessed environment, where people my age were getting “preventative” Botox, having their blood drawn for creams made of their own plasma, and dutifully recounting the minutiae of their daily lives—what they wore, ate, said, and put on their faces—for audiences on social media.

Suddenly, the banal consumerism so viciously mocked in American Psycho was everywhere. Now, when you search “Patrick Bateman morning routine,” you can find an AI-generated itemized list of the steps, presented as if to be followed. While working on youthjuice, my updated, feminized spin on capitalist horror, I found the only way I knew to accurately capture this absurdism I witnessed in the beauty industry was a similarly sardonic, cynical, and bloody point of view. Horror is uniquely equipped to reflect the realities of an often unreal-feeling world, and that’s in part because the genre can hold so many things at once: blood-and-guts, comedy, lyrical prose, complex characters, social commentary.

Without that visceral reading experience in the first week of college, I’m not sure I ever would have found my way to horror writing. But picking it up so many years later, I was delighted to find American Psycho’s multilayered cultural commentary, aspects I missed as a less mature reader. I may have traded the certain emotional vulnerability that allowed me, as an anxious teenager, to feel the book so deeply I was convinced Patrick Bateman was about to step out of my dorm room closet and wear my skin. In its place I gained a healthy cynicism that allows me to appreciate the fullness of its craft. Now I carry that balance into my own work, bringing my own blend of satire and gore. I hope Patrick would be proud.

***