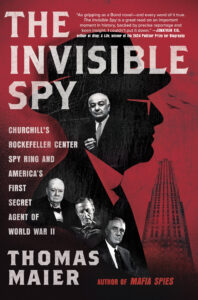

My new book, The Invisible Spy, is all about Ernest Cuneo, an ex-NFL football player who became America’s first spy of World War II, and how he worked secretly with Churchill’s spies at Rockefeller Center in the days before Pearl Harbor. This story tells how a mysterious Manhattan fatal accident involving Nazi spies was investigated by Cuneo and these British spies, including his friend Ian Fleming, the future creator of James Bond.

*

On the chilly Tuesday evening of March 18, 1941, two Nazi spies walked briskly through Manhattan’s busy Times Square, carrying secret papers in a leather satchel. The blinding streetlights and nighttime shadows shrouded them like ghouls full of malice and murder.

Wary of being spotted, the two undercover agents dressed like other nondescript men in winter coats, wool scarves and fedora hats on the streets that night. Mundanity served as their disguise. One German agent, with horn-rimmed glasses, clutched his briefcase as he weaved through the crowd. The other spy, shorter and with blond hair, followed along diligently. They’d just come from a Midtown restaurant, where money and important papers from their homeland had been exchanged.

As the curtains fell at nearby Broadway theaters and movie palaces, departing audiences poured into the Midtown intersection known as “the Crossroads of the World.” Flashing billboards and illuminated marquees cast a hazy glow above, as if protecting the city within a bubble.

There was little hint that the world was about to change, nor of the damage these two spies planned to inflict.

Most Americans were still isolationists. They didn’t want the long Depression to be followed by an endless war in Europe similar to World War I. The nation seemed asleep to the dangers it faced, both from afar and in its own backyard.

During the past two years, the military machine of German dictator Adolf Hitler had advanced across Europe without mercy. It had crushed France, Belgium, Poland, Czechoslovakia and the Netherlands. Great Britain—at war against the Nazis since September 1939—now seemed Hitler’s next target for invasion.

With bombs already falling on London, Prime Minister Winston Churchill gratefully accepted the American government’s “lend-lease” of aircraft, tanks, battleships and other weaponry that same month of March 1941, in a desperate attempt to save his United Kingdom.

Steadily, the White House expressed concern about Hitler’s aggression and talk of German spies infiltrating the United States. “Nazi forces…openly seek the destruction of all elective systems of government on every continent—including our own,” warned President Franklin Roosevelt in a speech on March 15, 1941.

Yet in many ways, America—still officially neutral—averted its gaze as Europe went up in flames.

In Times Square that night, none of the theatergoers strolling by were aware of the two Nazi spies scheming to blow up New York City. Most headed home safely. Others sauntered over to eateries and bars like Sardi’s for a nightcap.

However, the anonymity of the two German agents was shattered when they reached the intersection of Broadway, Seventh Avenue and 45th Street. The taller man with his briefcase suddenly crossed against a traffic light. His action—perhaps out of nervousness, perhaps in response to some perceived threat—proved catastrophic.

When the Nazi spy stepped off the sidewalk, a taxicab slammed into his body, knocking him unconscious. He collapsed onto the street along with his briefcase. An instant later, another oncoming car ran him over. The unforgiving vehicle cracked his skull like an egg.

The crash horrified onlookers. With broken bones and bloody clothes, the man remained on the pavement, unmoving. His flesh was exposed amid the cobblestones and cement. Nearly everyone in the crowd appeared transfixed by this tragedy—all except one.

Quickly, the other Nazi spy snatched the briefcase and fled the scene. He ignored his mortally injured companion. He left it to passersby to call for help.

When New York police arrived, detectives rifled through the dead man’s clothes, searching for his identity. Papers in his pockets claimed he was “Senor Don Julio Lopez Lido,” a message courier for Spain. Over the next few days, though, the Spanish embassy insisted there was no record of such a man. The stranger’s corpse remained unclaimed.

Through their investigation, the New York police found the dead man kept a notebook with the names of American soldiers and strategic places in the New York area ripe for sabotage. There was even mention of a naval base in the Pacific, a place called Pearl Harbor. Oddly, all of these papers were written in German.

The baffled New York detectives called in the Federal Bureau of Investigation, then led by J. Edgar Hoover, its much-celebrated chief. But Hoover’s “G-men,” as his government agents were touted in the popular press, couldn’t figure out the identity of the dead man from Times Square either. The answer wouldn’t come until another set of foreign spies—already implanted in America—provided a crucial and ominous clue.

Around this time, at their secret headquarters high atop Rockefeller Center in Manhattan, spies sent by Winston Churchill gathered to share intelligence with a little-known White House insider named Ernest Cuneo. He was the sole representative of the United States government in the room.

Cuneo was an imposing man, heavyset and prematurely balding. He spoke energetically and with the snappy diction of a New York tabloid. Street-smart and media savvy, he was a gregarious, Ivy League–educated lawyer who’d once played professional football in the NFL before working for the president. At age thirty-five, Ernie embodied the stereotype of the big brash American. He was inclined to use gridiron phrases in conversation with the British and Canadian spies, as if they were all on the same team.

This group of intelligence agents met throughout 1941 to discuss many confidential concerns. Their latest mystery—the unknown spy killed in Times Square—would be added to the list. Cuneo and Churchill’s secret agents, including the debonair Ian Fleming, future creator of the James Bond novels, talked discreetly about the Nazi threat inside America. They were determined to stop it—violently if necessary.

“The British are many things,” Cuneo later observed, “but cowards they are not.”

Rockefeller Center, with its Art Deco facades and stylish shops, seemed an unlikely setting for these secret meetings. From the skyscraper’s thirty-sixth-floor windows, passersby below appeared like innocent pawns, oblivious to the ongoing chess match of international intrigue above. But for these two nations, the “great game” of spying had never seemed more urgent.

Although America had yet to declare war, Cuneo had already become the country’s first spy of World War II. He knew how to keep secrets and a low profile, as if he were invisible.

“I always liked to keep out of sight,” Cuneo explained about his espionage task, which was especially difficult given his ample girth and booming voice. “Anonymity is freedom.”

For a while, virtually no one knew about this covert mission, set up by Churchill shortly after he became wartime leader of Great Britain in May 1940. This unprecedented foreign spy operation in the heart of New York City was unknown to virtually all Americans except Cuneo’s boss, President Roosevelt.

The British agents impressed Cuneo with hard evidence that Nazi spies had infiltrated America, hatching plots for sabotage and destruction at an alarming scale. The explosions planned by the two Nazi spies in New York City were similar in scope to the successful 9/11 terror attacks decades later. Bombs from Hitler’s planes had already killed thousands of civilians in London and throughout Europe, wrecking homes and lives and leaving cities in ruin. Yet the United States remained reluctant to join the conflict. Lending old battleships and weapons was one thing; sending troops to fight overseas was quite another.

Indeed, for many months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the White House assured Americans that they would avoid getting into the fight against Hitler’s regime.

During the November 1940 presidential campaign, FDR won an unprecedented third term with a promise of hands-off neutrality. “I have said this before, but I shall say it again and again—your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars,” Roosevelt told a Boston crowd shortly before Election Day.

By then, however, the covert actions of Cuneo and Churchill’s spies at Rockefeller Center belied FDR’s public assurances. They were already at war.

As a spy, propagandist and secret fixer for the president, Cuneo served as an unseen middleman. He fed confidential tips and government propaganda—from both the White House and Great Britain—to the most famous newscasters of his time, Walter Winchell and Drew Pearson, and to the nation’s top newspapers, reaching millions.

On numerous intelligence matters, Cuneo also acted as a key contact figure with the FBI, the Justice Department and the State Department. Eventually, he was appointed the official US “liaison” for the newly created Office of Strategic Services, headed by Colonel William “Wild Bill” Donovan—and the precursor of today’s CIA.

No one quite compared to Cuneo. He often acted alone, as if a free agent. Yet like a good teammate, he regularly joined British and Canadian agents in carrying out a massive espionage campaign inside the United States—the biggest of its kind at that moment in history.

About a thousand spies, informers, tipsters and double agents would report to William Stephenson, mastermind of the British Security Coordination, as this clandestine outpost at Rockefeller Center was known. Stephenson, a wealthy Canadian businessman and former World War I flying ace, carried out his secret mission with a charismatic sense of adventure.

Using the cable address “Intrepid,” which became his nickname, Stephenson executed Churchill’s wishes with vigor and cunning. Fellow spy Fleming was inspired enough to use Stephenson as an exemplar for his fictional James Bond character. “He [Stephenson] is a man of few words and has a magnetic personality and the quality of making anyone ready to follow him to the ends of the earth,” wrote Fleming.

As a spymaster, Stephenson understood the need to remain anonymous. Small and unremarkable in person, he could blend into a crowd without detection. As writer John le Carré later observed, “Few of the thousands who worked for him knew his name, let alone his face.”

Over time and over drinks, Cuneo would become close friends with Stephenson and Fleming. He liked to share caviar, cocktails and confidential information with these undercover British agents while they sat beside the fireplace inside Stephenson’s posh Midtown duplex.

Fleming, ever the wartime sophisticate, made sure the gin and dry vermouth he poured into his glass at their clubby meetings was prepared carefully, with what Cuneo described as the skill of a brain surgeon. Fleming preferred martinis—shaken, not stirred. He’d learned to smoke cigarettes with a holder held in place by his teeth. He was long and lean, certainly compared to Cuneo’s broad physique. He mixed quips and bon mots among his puffs. The two became unlikely friends.

“Know what I’d like if I could have anything I wanted?” Fleming asked Cuneo on one tipsy occasion. “I’d like to be the absolute ruler of a country where everyone was crazy about me.”

Both men burst out laughing, struck by the absurdity of the comment in a world dominated by an insane man—Hitler. Because they fancied themselves as writers, they enjoyed a good punch line or ironic twist to shield them from the ugliness of this reality.

After hours, Cuneo and Fleming liked to escort beautiful women—some of them spies as well—to various Manhattan hot spots, such as 21 and the Stork Club. One of them—Margaret Watson, an attractive Canadian staffer at Rockefeller Center—would become Cuneo’s wartime lover and eventual wife.

Given the sensitivity of his role as a White House intermediary working clandestinely with Churchill’s government, Cuneo had to be careful, and arguably the most discreet of all these spies. “Cuneo not only belonged to the President’s Brains Trust, but was in a sense its coordinator as well as its link with Stephenson,” recalled H. Montgomery Hyde, Stephenson’s director of security.

This cadre of foreign agents inside New York had a three-fold mission. Most visibly, they protected Great Britain’s shipping interests and vital supply lines needed for the ongoing war in Europe. As the Times Square incident revealed, they also conducted an undercover crusade against Nazis infiltrating the United States and the isolationist Americans who supported them.

But most important, Stephenson needed to convince America to join Britain’s ongoing war in Europe. His carefully cultivated campaign—built on propaganda, political influence and dirty tricks—aimed to change the mood of public opinion. Given the strong opposition of US pacifists and prominent German sympathizers, this task would be the hardest of all.

**

The undercover British spy operation in New York City, both audacious and likely illegal, was fundamentally a Churchillian idea. It was enacted with the unique daring and panache Winston exhibited his whole life. A prolific writer and historian (who later won a Nobel Prize in Literature), Churchill understood the power of words in determining a war’s outcome. He also admired the mental tenacity and physical courage of men like Stephenson.

The enigma of spying appealed to Churchill throughout his career. During the First World War, known also as “the Great War,” he reveled in the complexity of Britain’s secret service missions. “Tangle within tangle, plot and counter-plot, ruse and treachery, cross and double-cross, true agent, false agent, double agent, gold and steel, the bomb, the dagger and the firing squad, were interwoven in many a texture so intricate as to be incredible and yet true,” he described.

In this new war, espionage was even more complicated. The British couldn’t take public credit for their intelligence successes in America, lest they arouse the ire and suspicions of an anti-war citizenry. From their Manhattan hideaway, Churchill’s spies discreetly kept tabs on powerful isolationist Americans, such as Joseph P. Kennedy and Charles Lindbergh, and conspired against members of Congress and even those in FDR’s administration who opposed them.

They were aided by prominent Brits in the United States—including Charlie Chaplin, Cary Grant, Alfred Hitchcock and Noël Coward—who passed along what they heard in Hollywood as well as Washington’s social circles. “My celebrity value was a wonderful cover,” explained Coward. Even Churchill’s literary agent acted as an informer.

In this massive effort, no stone was left unturned, no spy tip ignored.

“For the British,” Cuneo explained, “it was a life or death struggle.”

That America lacked an adequate spy agency became brutally clear with the bloody Times Square incident in March 1941, a few months after Cuneo began his top secret work. While Hoover’s FBI remained clueless about the dead man’s identity, Stephenson’s team at Rockefeller Center had a good idea who he was.

For months, British spies had been secretly opening mail from the United States involving suspected Nazi spies and their German-American sympathizers. They sifted through letters and packages in Bermuda—on their way to Europe—without detection. Any signs of impending danger were reported to Stephenson’s staff in New York.

Some Nazi letters were written with invisible ink, as British chemists determined, made from a common drugstore powder given for headaches. Stephenson’s team figured out the dead German spy’s identity by reading one of these intercepted messages that contained a telltale clue.

The Nazi agent’s real name was Captain Ulrich von der Osten, of the German military intelligence agency known as the Abwehr. Von der Osten, a chief aide to the Abwehr’s legendary spymaster Wilhelm Canaris, had been sent to oversee Nazi covert operations within the United States. Hitler’s generals anticipated America entering the war soon and dispatched teams of their own German spies to thwart that effort. Using an alias, von der Osten spent two nights in a Midtown Manhattan hotel before his fateful collision in Times Square.

With Stephenson’s help, the FBI eventually caught up with the unknown companion who had fled the scene. His name was Kurt Frederick Ludwig, a German spy living in Queens, an outlying borough of New York, who used several aliases of his own.

If Ludwig thought he’d escaped successfully into the night, he was mistaken. In a remarkable stroke of luck, it was Ludwig’s letter to his Nazi bosses—read by British censors working in the basement of a fancy hotel known as “the Pink Palace” in Bermuda—that described the Times Square crash. It even named the hospital where von der Osten’s body had been taken.

Authorities quickly found Ludwig in New York but didn’t arrest him. Instead, over the next five months, they kept Ludwig under surveillance, slowly collecting evidence of a Nazi spy ring, until the FBI finally apprehended him and several of his coconspirators.

The eye-opening twist of fate at Times Square led to the exposure of other instances of German espionage within the United States. That same year, the FBI arrested eight Nazi spies plotting to blow up power plants and other industrial targets. But unbeknownst to most Americans, the Nazis weren’t the only ones with a foreign spy operation inside US borders.

***

As Cuneo began his secret mission in mid-1940, he realized that maintaining a good but hidden relationship with Churchill’s spies would be essential. He had entered a high-stakes gambit with these British agents, with their headquarters hidden in the International Building, way above the skating rink and Christmas tree at Rockefeller Center. Outside the building stood a tall bronze statue of Atlas, the ancient Greek god, carrying the proverbial weight of the world on his shoulders. To Stephenson and his staff, the fate of Great Britain seemed no less a burden. Room 3603 was the center of undercover activity for the British Security Coordination office. As camouflage, a small sign carried the deceivingly innocuous name “British Passport Control” on its door.

By any measure, Churchill’s undercover campaign in America was unprecedented, and far more extensive than the foreign spy efforts of either the Germans or the Soviet Union. Entrusting it to Stephenson, an inveterate risk-taker, was a calculated bet by Churchill that could blow up at any time.

Describing these risks, Cuneo later said Stephenson’s BSC espionage agents “tampered with the mails, tapped telephones, smuggled propaganda into the country, disrupted public gatherings, covertly subsidized newspapers, radios, and organizations, perpetrated forgeries—even palming one off on the president of the United States (a map that outlined Nazi plans to dominate Latin America)—violated the aliens registrations act, shanghaied [sic] sailors numerous times, and possibly murdered one or more persons in this country.”

This game of spying in the US had no rules, no assurances of safety. Cuneo’s own part in sharing information with foreign spies might have been judged as treasonous by FDR’s critics if they’d found out. But Cuneo believed Churchill’s secret spy mission was vital to saving Western civilization from the looming threat of Hitler.

“My father…carried out things that Roosevelt wanted done, but Roosevelt needed deniability,” recalled his son Jonathan Cuneo, a prominent Washington attorney. “He said if it ever came out what the British did, Roosevelt would be retroactively impeached. My father was a real idealist. If he thought it was the right thing, he did it.”

Over time, Cuneo learned of a British “disposal squad,” getting rid of those collaborating with the Nazis. He heard talk that the “accidental” Times Square killing may have been deliberate. In his unpublished memoir, Cuneo also made a fleeting reference to a British agent killed by a German spy near the intersection of Manhattan’s 89th Street and East River Drive, not far from Gracie Mansion, the New York City mayor’s residence.

This exchange of violence, no matter how discreet, was all part of the murky period before the US government formally went to war. As a go-between for the president, collaborating with a team of British spies, Cuneo made up his own rules of engagement as he went along. So did the man he referred to as “Intrepid.”

“For security reasons, I can’t tell you what sort of job it would be,” Stephenson confided to Cuneo about his team’s activities in the United States. “All I can say is that if you join us…you mustn’t be afraid of murder.”

___________________________________