Political violence is defined as acts perpetrated to achieve political goals, and can include war, military coups, genocide, state repression, terrorism, guerilla warfare, and assassinations, as well as the violence associated with racism and sexism. Revolution in 35mm: Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960–1990, a new book I’ve co-edited with New York critic Samm Deighan, examines a thirty year stretch of cinema and how filmmakers from around the world reacted to the political violence of the period on screen.

One of the key themes running through many of the films included in Revolution in 35mm is that so much of this violence is criminal, whether the crimes are directly committed by the state actors, gangsters or the rich and powerful in the defence of their political and economic interests. Of course, many of the films also depict violence carried out by those resisting this crime and corruption with the stated aim of combatting dominant power structures, but which take a heavy toll on life.

Our book covers the historical period from the Algerian war of independence and the early wave of postcolonial struggles that reshaped the Global South, through to the collapse of Soviet Communism in the late 1980s. It includes work from the French, Japanese, German, and Yugoslavian New Waves, Latin America’s ‘New Cinema Movement’, and subgenres like spaghetti westerns, Italian poliziotteschi, Blaxploitation, Hindi gangster films and mondo movies. It also looks at how protest movements by students, workers, and leftist groups, as well as broader countercultural movements such as Black Power and feminism, connected with and expressed their values – including their relationship to political violence – through cinema.

If you want to get a sense of just how broad our coverage of films is, check out my Letterboxd of every title mentioned in Revolution in 35mm. Although it’s hard to pick favourites from such a large and diverse body of work, here are ten of the films I particularly enjoyed rewatching or discovering in the process of putting the book together.

Cairo Station (1958)

Egypt has been the Middle East’s largest film producer, and one of its leading lights was Youssef Chahine, who directed 46 films from 1950 to 2007 (he died in 2008). Cairo Station centres on a series of murders taking place around Cairo’s main train station. Against this backdrop, Chahine explores the obsession of a disabled newspaper seller (played by the director) with a young woman who works as a semi legal drink seller at the station, as well as official corruption and labour unrest. Cairo Station’s themes, including what for its time was a pretty daring approach to the representation of women, the portrayal of working-class Egyptians, and the struggle of the poor against corrupt businessmen or government officials, echo throughout much of the director’s later work.

A Bullet for the General (1966)

The spaghetti western exploded in popularity in Italy following the success of Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars in 1964. A subset of this body of cinema was the ‘Zapata’ spaghetti western. Set during one of Mexico’s post-1900 periods of revolution, these films depict downtrodden peasants who become politically enlightened revolutionaries after fighting oppressive government officials and soldiers. Directed by Damiano Damiani, A Bullet for the General tells of El Chucho (Gian Maria Volonté), a bandit who specialises in stealing guns for revolutionary forces under the leadership of General Elias. Chucho accepts the help of a smooth talking American (Lou Castel), unaware the newcomer is a contract killer paid by Mexican officials to kill Elias. The film features the frenetic violent action characteristic of Italian westerns, with a plot that acts as a cypher for both the conflict between Italy’s impoverished south and industrialised north, and the wider struggle of the global south against the global north.

If (1968)

Lindsay Anderson began his film career as co-founder of Britain’s Free Cinema movement in the mid-1950s, then went onto participate in the country’s filmic new wave in the early 1960s and its focus on depictions of tough, often male working class figures. He is best remembered, however, for ‘the Mick Travis trilogy’, If, O Lucky Man (1973), and Britannia Hospital (1982). All three films star Malcolm McDowell and are biting satires that gave vent to Anderson’s cultural alienation and critique of British imperialism – a position shaped by his early years as the son of a British army officer in southern India and his military service during WWII. In If, Travis and his circle of misfit friends face the bizarre rituals and horrors of an upper class boarding school, particularly abuse at the hands of “Whips,” older boys. As the Whips become more controlling and violent, Travis and his friends have their revenge by uncovering the weapons stash that belongs to the school’s military cadet program and staging a bloody revolt. A surreal, anarchic tale with obvious parallels to the political upheaval gripping the world at the time.

Z (1969)

Costa-Gavras’s film is based the real-life murder of Greek politician Grigoris Lambrakis in 1963. A member of the communist faction of the Greek resistance during World War II, Lambrakis become a prominent opponent of American interference in Greek affairs. His assassination was covertly supported by members of the Greek police and military, who went on to play key roles in the military coup of 1966, which resulted in a brutal ten-year dictatorship. There is so much I love about this film: the propulsive narrative, which borrows heavily from both neorealism and the policier; the score, the luminous cinematography, and the wonderful cast, including Yves Montand, Irene Papas, Jean-Louis Trintignant, and Marcel Bozzuffi as the most ruthless of the thugs who organizes the assassination. However, my views on Z were deepened considerably by Christos Tsiolkas’s essay on it in our book, which analyses the film from a queer Australian migrant perspective.

The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1973)

The political convulsions gripping the USA in the late 1960s and early 1970s were depicted in a number of American films over the period, many of which are covered in our book. The Spook Who Sat by the Door is one of the most interesting. Based on a novel by Sam Greenlee, it follows Dan Freeman (Lawrence Cook), one of several Black men recruited by the CIA to burnish its racial credentials. But while the other recruits are content to take advantage of the upward mobility offered by the job, Freeman is motivated by other concerns, namely how he can use his CIA training to ferment Black revolution. United Artists were horrified by the film’s politics but contractually obligated to release it. However, it only played in a small number of cinemas before being pulled. Greenlee claimed there was a plot, orchestrated by the FBI, against the film, which involved confiscating prints and threatening theatre owners. It was then largely unavailable until the early 1990s and has very recently been remastered by the Library of Congress and The Film Foundation.

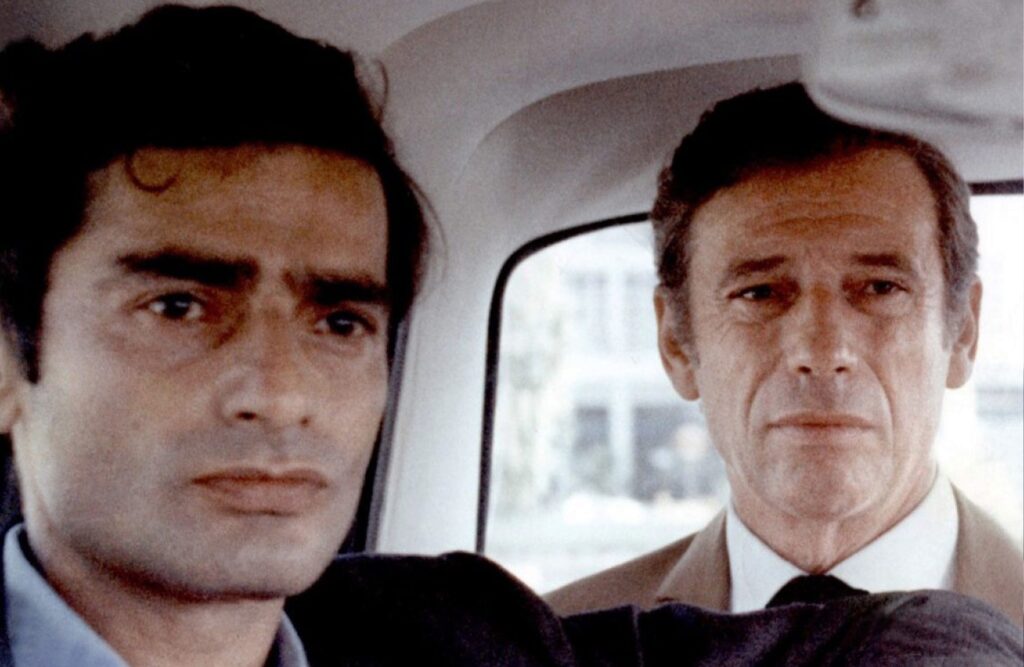

I Am Afraid (1977)

A poliziotteschi adjacent tale directed by Damiani, I Am Afraid stars Volonté as Graziano, a grizzled police detective assigned as a driver and bodyguard to an elderly judge investigating death of a shopkeeper. When the judge is murdered, Graziano becomes ensnared in a web of political intrigue around the case and its links to the trafficking of arms and explosives, some of which were used in a far-right train bombing, and the involvement of far right members of Italy’s intelligence service. I Am Afraid is a complex, pessimistic thriller and Volonté is stunning in it as a man literally driven to the edge of his sanity by the violence, lies, and secrets of the Years of Lead.

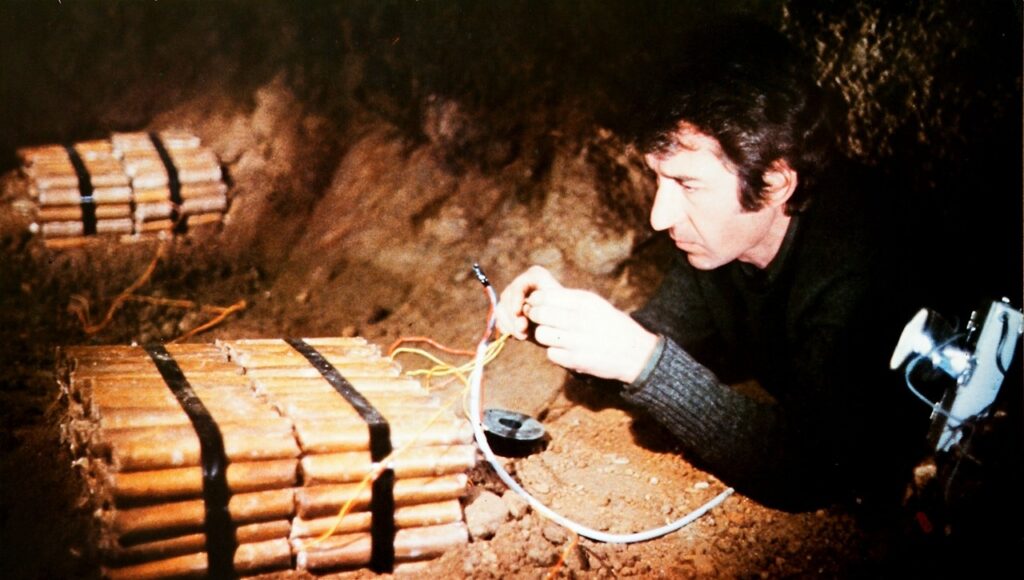

Ogro (1979)

Gillo Pontecorvo is best known for The Battle of Algiers (1966), which became a call to arms in a period of growing anti-colonial struggles and a how to manual for a host of Third World liberation struggles and urban guerilla movements in the north. But four out of his five films can be viewed as a sustained exploration of the practicalities and impacts of using political violence. Of these, my favourite is the Italian/Spanish coproduction Ogro. Ogro is based on a real event, the 1973 assassination of Admiral Luis Carrero Blanco, right-hand man and successor to then-ailing Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, by members of Basque guerilla group ETA. The film is a much more downbeat and nuanced discussion of political violence than that contained in the director’s earlier work, influenced as it was by Pontecorvo’s concerns over the mounting political violence during the Years of Lead in his home country of Italy, and the fragile status of Spain’s democracy following the downfall of the Franco regime in 1975.

Seven Days in January (1979)

Unhappy with the end of 36 years of dictatorship and the transition to democracy in Spain in the second half of the 1970s, die-hard fascists in the country’s business, military, security services, and political elite, staged various provocations to sabotage the shift and return to fascist rule. The highest profile of these was the ‘Atocha massacre’, a far right attack on a trade union office, in which five people were killed and four seriously wounded. An outspoken critic of Franco and member of the Spanish Communist Party, Juan Antonio Bardem’s Seven Days in January examines the lead up to the killings and their aftermath. Although it does this from multiple points of view, the main perspective is that of an impressionable young man, the son of a prominent fascist family, who takes part in the attack and is then cut adrift when the anti-left backlash the attackers had hoped for fails to materialise.

Born in Flames (1983)

One of several second wave feminist films in the 1980s that examined themes of political violence, Lizzie Borden’s Born in Flames is set in a future New York when a peaceful socialist revolution has taken place, but is failing to achieve it liberatory goals, particularly for women, and especially for women marginalised by their colour and sexuality. It blends documentary and science fiction tropes to present a series of scenes of women from different backgrounds and with varying conceptions of what feminism is – some of whom support political violence – attempting and to come together and find a common platform for revolution, and the state’s response. Born in Flames was made on a shoestring budget over several years and boasts a largely amateur cast. Despite this, indeed probably because of it, the film exhibits the most wonderfully manic, almost punk energy – qualities reinforced by the terrific soundtrack – and it evinces a real sense of what debate looks like in a diverse political movement.

Macho Dancer (1988)

Film maker Lino Brocka got his directorial start on the Filipino equivalent of anthology television shows such as Kraft Theatre. The bulk of his career, which was tragically cut short by a car accident in 1991, took place under the dictatorship of military strongman Ferdinand Marcos. Brocka, who was also openly gay, was deeply involved in the opposition to Marcos and what is referred to as the “People Power Revolution” that deposed him. His films mobilised the melodrama and crime tropes popular with Filipinos to explore issues such as colonialism, poverty and opposition to corruption. Macho Dancer tells of a young man, Noel (Daniel Fernando), who leaves his poor rural village for Manila and finds work as a dancer in a gay strip club catering to foreign sex tourists. Noel befriends another sex worker, who is searching for his young sister. Working together, they eventually locate her in a brothel protected by a brutal policeman and decide to rescue her, with violent consequences. Released after the dictatorship, the film nonetheless proved to be incredibly controversial with the country’s censors.