I met Anjili Babbar smoking cigarettes at Bouchercon last year (she has since quit), and thought, this chick is really cool. And also, she knows a lot about Irish crime fiction. Babbar is, in fact, the author of an excellent new work on Irish crime writing, aptly titled Finders: Justice, Faith and Identity in Irish Crime Fiction. As a child of academics who has read a fair amount of jargon-filled research, I can confirm Anjili is the rare academic who can explore deeply intellectual topics in a way that is not only, well, readable, but also fascinating. I asked Anjili a few questions about her new book and her take on the past, present, and future of the Emerald Isle’s many (fictional) mysteries.

MO: Why Irish crime fiction? And why now?

AFB: Some of the grittiest, most socially relevant crime fiction is currently coming out of Ireland, which I think is fascinating because the genre didn’t really take off there until the twenty-first century. I wanted to explore this late renaissance—what caused it, and how it paved the way for a novel, idiosyncratic approach to the genre.

MO: How does the Irish crime novel fit in with larger trends in crime fiction (or within Irish literature)?

AFB: Irish crime fiction is such an interesting tapestry, in terms of both influence and content. I think of it as a running dialogue among diverse traditions and perspectives, in which tropes or standards are used, challenged, altered, or subverted. For example, an exploration of identity is crucial to Irish literary tradition, but following the Irish Literary Revival, that has often translated to a presumption that an author’s primary charge is to define Irish identity. Irish crime writers firmly reject that notion, and in their work, identity becomes something more complex: affected by culture and history, certainly, but also deeply individual.

Similarly, they use the tropes of crime fiction, but they also remind us that some of these tropes ring hollow when they are removed from a British or American context—and, in particular, when they are applied to the context of sustained national violence or its aftermath. Adrian McKinty does a wonderful job using intertextual references to get this point across: there is a certain absurdity to expecting justice on a case when the local police force is both besieged by paramilitary violence and the object of general mistrust. Columbo wouldn’t fare well in Belfast during the Troubles.

Of course, all crime fiction is concerned with justice, but the thing I find most interesting about Irish crime fiction is that it interrogates what “justice” actually means. It might mean different things to different people, or even different things to the same person at different times. And it might be that, as we conceive of novel paths to pursue it, we overlook some genuinely good ideas from systems that, as a whole, have fallen short of our expectations. Early crime writers largely prioritized logic over faith or religion; hard-boiled writers shed light on legal corruption; but Irish crime writers suggest that there might be salvageable points from both legal and religious systems which, when combined with personal ethics, can bring us at least a step closer to understanding what justice looks like for us.

MO: How does Northern Irish crime fiction compare to the rest of Ireland?

AFB: It’s difficult to answer this succinctly, because there is so much variety in the approaches of the individual authors. Of course, the specter of the Troubles is more evident in works from the North, because the conflict was happening during many of the authors’ formative years. But we are also talking about a small island where people frequently have relatives and friends on both sides of the border, so it’s natural that there is some overlap of concerns. There are palpable efforts to contend with and address historical trauma across the board—whether that trauma relates to the Troubles, abuse scandals in the Catholic Church, or personal history—and these often take the form of very dark humor. There is a concern with the question of progress on both sides of the border, and specifically, who gets left behind in that progress. In the North, that comes with the warning that some of the factors that led to sectarian resentment, including poverty and mistrust in the government, still exist.

MO: How does the rise of the Celtic Tiger and increasing globalization make its way into Irish crime fiction?

AFB: We often see characters grappling with their feelings about rapid social change and modernization in crime fiction from the Republic. On the one hand, the diversity that accompanied the Celtic Tiger is always described in a positive light, with suggestions that multiculturalism and multifarious perspectives are a salve for the prejudices of the past. A quote from Ken Bruen’s Jack Taylor as he reflects on contemporary Galway comes to mind: “Keep the city moving, keep it mixed, blended, and just maybe we’ll stop killing our own selves over hundreds of years of so-called religious difference.”

On the other hand, there is skepticism about increased materialism and commercialism. That sometimes takes the form of a very tempered nostalgia, by which I mean that characters acknowledge that their yearning is for an idealized version of the past—a version engendered by their former innocence—rather than for the past itself.

MO: How can crime fiction address social issues?

AFB: I actually think that crime fiction is an ideal vehicle for exploring social issues, because it gets to the heart of people’s priorities, their visions of justice, and the way they act under pressure. The authors I discuss in Finders tackle issues like women’s health and child abuse in Ireland, and they offer outsiders’ perspectives on a number of American issues, too, like the health care system and recent developments in American politics. Sometimes they draw connections among cultures, as in discussions of systemic prejudice and the dynamics that reinforce generational poverty. But possibly the most poignant issue in the context of contemporary global issues is tribalism. The Troubles are a clear example of the extremes to which tribalism can take us and the anaesthetization to human loss that can result. One theme that comes up repeatedly in Irish crime fiction is fatigue from the pressure to blindly embrace optimism for the future, which can include both a disallowance of mourning and a failure to address underlying issues that led to tragedy and inequity in the past. Adrian McKinty, whose Duffy series is set during the Troubles, warns that what happened in the North could happen anywhere; Brian McGilloway’s contemporary Lucy Black series builds on that, suggesting that Brexit and present-day manifestations of bigotry and xenophobia are reminders of the fragility of progress. The idea is that we need to be mindful to not fall into dangerous patterns, and to remember our shared humanity, even when we don’t seem to have a lot of shared ground—and Irish authors are in a unique position to make that argument.

MO: How do contemporary social issues tend to be portrayed in Irish crime fiction, especially thoughts on gender?

AFB: Perspectives on social issues tend to lean very liberal, and as in McGilloway’s work, a direct line is often drawn between current social issues and lessons learned from the traumatic history of “othering.” The tribalism that led to the Troubles is used to shed light on racism, xenophobia, homophobia, and gender prescriptions.

That last consideration has an enormous impact on the way that women are portrayed in Irish crime fiction. The trope of woman-as-victim is subverted in a number of ways: missing women who have agency and have gone missing of their own accord, strong women detectives, and the female gaze (especially in the works of Claire McGowan), among others. Eoin McNamee’s Blue Trilogy explores the tendency to impose fairy tale constructs on women who actually are the victims of violent crimes—to “other” them and imagine that they must have strayed from some moral (or gender-prescribed) path to invite their fates. It’s a way for people to reassure themselves that they and their loved ones are safe from similar victimization, of course, but it also prevents us from addressing core social issues.

MO: What was your research process like?

AFB: I did not grow up in Ireland, and I wanted to get as many first-hand perspectives as possible from people who did, so my process was a bit unconventional for a work of literary criticism. Of course, I read a lot of Irish history and essentially everything that had already been written about the texts, but I structured the book around lengthy conversations with the Irish authors about their work, their goals, and their backgrounds. I also talked to officers from the Police Service of Northern Ireland about Troubles history and post-Troubles paramilitary activity. And I interviewed Colin Dexter, whose Inspector Morse series provides intertextual references for some of the Irish writers in my book.

I also traveled, a lot. I visited several of the locations where the authors’ books were set, the Police Service of Northern Ireland Headquarters in Belfast, the Royal Ulster Constabulary Museum (among others), and the RUC Garden of Remembrance.

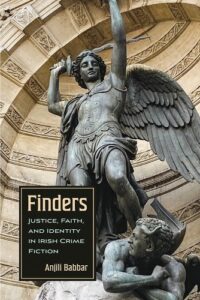

Finally, since Finders is divided into three sections based on saints that are used as symbols in the texts—Saint Anthony of Padua, the Archangel Michael, and Saint Christopher—I explored the history and tradition of those saints, too. I spent several weeks in the theology stacks at the Bodleian library in Oxford; then I visited the statue of Saint Anthony in the Oxford Oratory (which features in the final Morse book and is alluded to by Ken Bruen in The Guards), the Shrine of Saint Anthony in Maryland, the Fontaine Saint-Michel in Paris, and the Castel Saint’Angelo in Rome. I asked volunteers to recount their versions of the saints’ histories, and the importance of these saints in their own faith systems.

A lot of the research didn’t make it into the book in a literal sense, but I think it was crucial for me to have a fuller understanding of historical, literary, social, political, and religious contexts. I feel strongly that these authors have a lot to contribute to the crime fiction genre (in terms of style, content, and social commentary) and to discourse about justice more broadly—so I really, really wanted to get it right.

***