In death, there is silence—and yet the body remains as testament to the story of its demise.

In cases where the reason is unknown, unexpected, or thought to be unnatural, a Medical Examiner-Coroner is brought in to determine the cause and manner of death. And while these individuals give voice to victims of violence (and other maladies), they seldom seek out the spotlight; rather, their presence is largely confined to crime scenes, office buildings, and courthouses. Perhaps the most notable real-world exception to this general rule of conduct is Dr. Thomas Noguchi, Hollywood’s onetime “Coroner to the Stars.”

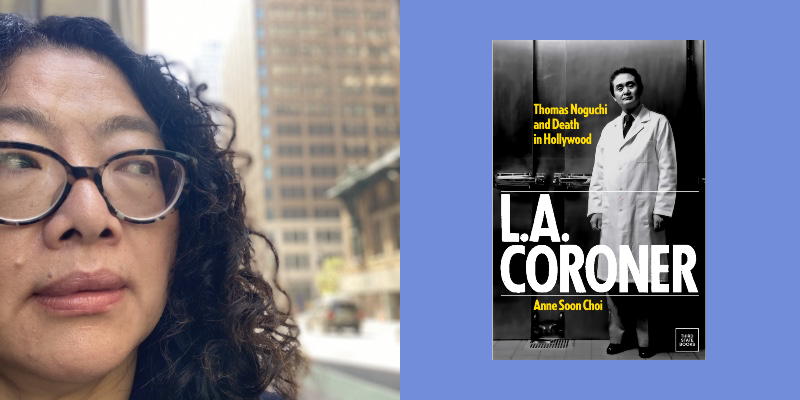

The highest ranking Japanese American official in Los Angeles County during the 1960s and 70s, Noguchi was once nearly as celebrated a figure as those whose bodies he examined (Marilyn Monroe, Robert F. Kennedy, Sharon Tate, and Natalie Wood among them). However, his public profile and controversial commentary coupled with alleged administrative shortcomings began to overshadow his keen intellect and ingenuity, resulting in the threat of professional dismissal and disgrace. Noguchi’s story of triumphs and travails is told in full for the first time in Anne Soon Choi’s L.A. Coroner: Thomas Noguchi and Death in Hollywood (Third State Books; April 22, 2025), a compelling narrative that melds biography with culture, history, politics, and true crime.

The book is an expansion of the author’s earlier piece, “The Japanese American Citizens League, Los Angeles Politics, and the Thomas Noguchi Case,” which won the Historical Society of Southern California’s best essay prize in 2021. In many ways, Choi is uniquely qualified to tell Noguchi’s story; not only is she a historian and a recognized authority in Asian American studies and the evolution of Los Angeles and its citizenry but a lover of mysteries, all of which lends itself to her scalpel-sharp inquiry into the man and the mythology.

Now, Anne Soon Choi shares how a chance encounter with a book served as the impetus for her interest in Thomas Noguchi as a research subject and eventual interviewee …

John B. Valeri: What drew you to Thomas Noguchi as a biographical subject? How did your background and education lend itself to researching a historical figure and period during which he was most prominent?

Anne Soon Choi: When I was in my 20s, I spent a lot of time at the Strand Bookstore. I was always looking for a good mystery (primarily to distract myself from making the decision of what I was going to do for the rest of my life!). On a really hot day—it must have been July or August, I remember how hot and thick the air felt and the smell of New York City in the summer—I found a copy of Thomas Noguchi’s memoir Coroner in the $1 bin. It was the first time I had encountered a memoir written not only by someone Asian American but a coroner! There was something about Noguchi’s story—his struggles, his flaws, his triumphs, and his involvement in some of the most famous death investigations of the 20th century that captivated me. Eventually, I decided to do something practical (!) and earned a Ph.D. in history at the University of Southern California and living in Los Angeles profoundly shaped my writing sensibilities. And as a US 20th century immigration historian I eventually wrote an article about Thomas Noguchi that won a prize in my field which led to this book. I was also fortunate as a graduate student to meet the author and activist Helen Zia who told me that Asian American history was hidden in plain sight, and it was true in the case of Noguchi. Once I began archival work, his story was everywhere.

JBV: The book is an expansion of an award-winning essay you wrote for Southern California Quarterly. Tell us about the process of lengthening your original piece. What were the most challenging and liberating aspects of working within a larger framework while maintaining the integrity of the original?

ASC: I think the hardest part of expanding the article was finding the right angle to take. The article really focuses on Noguchi and the Japanese American community and particularly the activities of the Japanese American Citizens League. This is certainly part of the book but only one part of the story. My agent Michael Signorelli was an excellent sounding board as the article was expanded and suggested looking at Noguchi’s cases to tell his story rather than a straightforward biography. Once this framework was in place, in many ways Noguchi’s story was hiding in plain sight in a wide range of archives. I spent a year doing archival work and I was also fortunate to be able to interview some of the key players in this story including Dr. Noguchi. The most challenging part of this project was to stick to Noguchi’s story because he was part of so many fascinating events. The most liberating part was to write a book for a popular audience and to bring Noguchi’s story to a non-academic audience. I was fortunate that Third State Books was willing to stick to this vision of the book which focused on Noguchi experiences rather than just on famous cases.

JBV: Dr. Noguchi was dubbed the “Coroner to the Stars,” given his involvement in high profile cases. In what ways was he a product of the growing celebrity culture? How did that both enhance his reputation and contribute to his eventual downfall?

ASC: Only in LA can a coroner become a celebrity! Noguchi was a consummate showman and if we use the current framing of celebrity—he is the OG influencer. He understood instinctively how to ride the wave of media attention until he didn’t. At the time, he was probably one of the most well-known Los Angeles County public officials which was no small feat for a coroner. And being the “coroner to the stars” did enhance his reputation to the extent that he was nationally recognized not only as a celebrity coroner but because he was the leading expert in forensic science. Indeed, the entire CSI franchise would not exist without Thomas Noguchi. At the same time, his growing need for media attention would contribute to downfall. He would lose his job, his wife, and it would even compromise his professional judgement. But even at this low point in his life, he overcomes this setback and returns to forensic research and teaching and mentors generations of pathologists which served his better nature.

JBV: Dr. Noguchi possesses a unique personality and skill set that made him a formidable pathologist but, arguably, a lackluster administrator/supervisor. In your opinion, what were his greatest strengths and flaws? How did the demands on the job and lack of resources – which remains a problem still today – accentuate the latter?

ASC: His greatest strengths included his deep knowledge of forensic science and his fierce commitment to maintaining the independence of the coroner’s office. Despite numerous attempts to separate the medical and administrative roles of the Chief Coroner-Medical Examiner in the 1960s and 1970s, Noguchi believed that such a move would diminish the power of the office and specifically—his power. Given the open hostility toward him, he was right to not give away the administrative control of his job. While Noguchi at times wasn’t always a great administrator, it should be remembered that after his ouster, his replacement found himself in the exact same situation as Noguchi and eventually resigned noting that the ongoing lack of resources. For Noguchi, the lack of adequate funding did make his job much more difficult, but his cultivation of his own celebrity also contributed to the scrutiny that he faced in the 1980s.

JBV: The calls for Dr. Noguchi’s removal/demotion allows you to explore the complexities of the generational divide within the Japanese American community. How was this illustrated through his plight(s) and need for public support? Beyond that, what of his circumstances resonated with African Americans and Latinos, who also advocated on his behalf in large numbers?

ASC: Noguchi was part of the postwar migration of Japanese Americans—the Shin Issei (new immigrants) and generationally he was the same age as the Nisei (second generation) who in Los Angeles spent the war years incarcerated in US concentration camps. After the end of the war, the majority of Japanese Americans in LA who had their lives destroyed during the war turned their attention to rebuilding their lives and very few people talked about wartime incarceration. For many in the community, the immediate decades after the war involved keeping their heads down and pursuing economic stability in the form of higher education and stable employment. City, county, and federal employment with its clear guidelines for promotion seemed a safe bet from the private sector that had no qualms about discriminating against Japanese Americans.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Noguchi was the highest ranking Japanese American in the County, and this was the confirmation for the community that the public sector was a place where Japanese Americans would be treated fairly until Noguchi was fired the first time. At the same time, many in the Japanese American community felt that Noguchi especially his need to be in the spotlight as unseemly and their support only came when it was 100% clear that racial discrimination was at play. The second time that Noguchi was fired in the 1980s unfolded differently. Very few of the Japanese Americans that supported him during his firing the first time were willing to support him. Partly because his administrative shortcomings were well known but also because the community was involved in the legal campaign for redress for their wartime incarceration. In this context, many believed that Noguchi’s plight was of his own making.

Much of the support that Noguchi received from the Black and Latino community stemmed from the fact that he was employed in the public sector. Blacks and Latinos like their Asian American counterparts were acutely aware that public sector employment was a pathway to upward mobility and because of this their interests were aligned. At the same time, Noguchi’s outspokenness on police shootings earlier in his career and his unwillingness to abandon the coroner’s inquest which allowed for a degree of public accountability of law enforcement in the shooting deaths of Black and Brown people generated support for him within these communities. It also helped that community leaders including Tom Bradley who would go on to be mayor of Los Angeles, Johnnie Cochran, and Dr. Francisco Bravo, one of the most prominent Mexican Americans in the city vouched for Noguchi.

JBV: In certain instances (e.g. Marilyn Monroe, Bobby Kennedy, Natalie Wood, etc.), it’s hard to separate the cases/individuals themselves from the hints of conspiracy that surround them. What was your approach to presenting this material without getting bogged down in minutiae? And how did you find that Dr. Noguchi’s conclusions and public commentary contributed to the ongoing speculation, no matter how inadvertently?

ASC: It was difficult to navigate the complicated terrain of conspiracy around his most famous cases because they have such a deep hold on American culture. I also did not want to rehash the same stories ad nauseum. The key was to focus on Noguchi and his role in these cases which surprisingly have not merited significant attention. At the time, Noguchi’s very public commentary as the coroner of record was a significant departure. He was deeply committed to the idea that the work of the coroner was not only to speak for the dead, but that understanding death was critical to improve the lives of the living and the coroner’s office needed to be independent. At the same time, he enjoyed the spotlight, and he knew how to play the media to his advantage. And part of keeping the media engaged was to make sure that the Coroner’s Office was front and center. This meant that his oftentimes provocative commentary did raise questions, and it became grist for the conspiracy mill.

JBV: In the book’s acknowledgments, you note that Dr. Noguchi made himself available to interview. What was it like to come face-to-face with the man himself after spending so much time and energy exploring his life and career?

ASC: I had a chance encounter with Dr. Noguchi and he was gracious enough to be interviewed. At this point, the manuscript was done. I had attempted to contact him through official channels but to no avail. We had a lovely interview where he answered my many questions. Meeting him at the end of the writing process was really powerful because after all the archival research, here was Dr. Noguchi in the flesh. At age 98, he has outlasted his critics and, in many ways, history is on his side.

JBV: Leave us with a teaser: What can readers expect next?

ASC: I write across genres, and I have an adult mystery that is not surprisingly set in LA that my agent will be taking out on submission. I am also in the early stages of a new true crime book set in southern California but this time in the 1990s in Orange County.