The first thing she does after watching the news is call her son. Come home, Iván, she wants to say. Come before it gets worse, and stay with me through the storm. But instead, after apologizing for interrupting his routine in the city, she tells him the contrary:

“Don’t even think about getting on the road tomorrow.”

It’s Thursday, and school’s just started. Iván is supposed to spend the weekend at home. But she wants him to stay in Murcia. Even if the news there is worrisome too. Better there than on the roads. She’ll have to be alone. But anyway, she always is. He could come see her every week. Every day, if he wanted. It’s just forty minutes from the capital to the village. But he’d always been determined to live close to school. It was better for his studies. Commu nications and media. What he really wanted to study was film. At least he didn’t go to Madrid.

He’s better off there, she thinks to herself, far from the sorrow, the melancholy of home. But today she wishes he was close to her. So she could protect him from the storm. Even being with him in the city would be better. To not feel the difference, short as it may be. Distance always means possibly not getting there in time. Being late. When there’s nothing more you can do.

“Don’t worry, Mom, I won’t leave. I’ve got stuff to do this weekend.”

This eases her mind, but in her heart, she wishes he’d argue with her, not yield to common sense. What do you mean, don’t come, Mom, how could I leave you there and stay here just because I have stuff to do? How could I not catch the bus, or drive, or even walk under the rain to make it home so the two of us could hold each other and keep each other warm? How could I not drop everything, Mom, to be with you as the sky rips open and everything collapses? No, Iván just says, don’t worry, he’ll be fine, as if nothing were happening, as if he felt free of the obligation to have to return to a home marred by afflictions.

After dinner, Dolores peeks out the window. It’s still raining hard. Lightning gleams on the stream where the street once stood. Soon after comes the thunder, its roar encircling the house.

She remembers all at once what happened three years ago, in December of 2016. No one could forget. The rain, the flooded ravines, the swamped streets. She’d seen something like that as a teenager too. The town was cursed, she’d told Clemente Artés that afternoon. But it’s also fated to resist, to rise up over and again, not caring that the world was going to hell. Every time the rain comes, though, the disquiet and uncertainty return. The fear. The resignation.

Hopefully this time it will blow over. She unplugs the TV. Unscrews the coaxial cable. She’s never known why she does this, but her mother used to do it too. Or unhook the antenna, rather. The antenna attracts lightning, she used to say. The TV does, all electronic appliances do. It also hits the plumbing and it can come out if you open the tap. One neighbor had to have his finger amputated, another had lightning come right through his window. So you close everything and keep quiet, play hide-and-go-seek. This is just superstition, she thinks, but she can’t help it, it’s part of the ritual when the storm comes. Like checking the batteries in the flashlight and getting the candles and lighter ready in case the power turns off.

Tonight, though, the lights have held out. Still, she keeps the angular flashlight on her nightstand, with a candle stuffed in an empty beer bottle next to a lighter. She picks up the book Clemente Artés gave her. It’s not the best reading for a stormy night. But it’s piqued her curiosity.

When she opens it, the old man’s aroma returns. And she smells something else this time, not just cut wood, but a vinegary scent that reminds her of fixer in a tray. She’s sure of it: that scent impregnates the entire book. She finds a large whitish spot on the cloth binding. And more than one wrinkled page. As if he’d spilled fixer on the book itself. She strokes the cloth and turns the wavy pages. Then, instinctively, she brings them to her lips. The book smells like photography, and it tastes like it too.

Perhaps for that reason, everything she reads that night takes on a special bodily reality, even the dedication, which confronts her as soon as she’s begun leafing through it: To Gisèle, in life and in death.

She doesn’t intend to read it now, but she can’t help glancing at the index and introduction, along with a few of the photographs. Right away, she realizes Clemente Artés isn’t an essayist, exactly. The book is a kind of inventory, tallying works, compositional techniques, iconographical information. There is a ten-page introduction and several paragraphs before each selection of images. The illustrations vastly exceed the amount of text.

Like every photography aficionado, Dolores knows of the tradition of mortuary photography. It’s mentioned in the histories of photography she has at home. It’s an old practice, one that has always put her in mind of nineteenth-century eccentricity, a strange custom from the beginnings of the art, one of many pathways that receded and vanished in time.

In his introduction, Clemente Artés delves into the origins of postmortem photography, the last image, as he apparently prefers to call it. The tradition of represent ing the dead predates photography and lies in the very origins of art itself. “The mystery of life and death,” he writes, “the beginning of representation.” Artés alludes to Pliny the Elder’s fable about the origin of art: the Maid of Corinth traces on a rock the silhouette of her beloved before he embarks on a long journey. “The image as a form of mourning, as the memory of an absence.”

Mortuary photography is the drawing into the present of the last image—an attempt to capture what is on the verge of being erased. It is linked to the spread of photography in the modern era. “Everyone had to have a photo. Not to have one meant not to have existed. Not to have one was to run the risk of not being remembered.” Throughout, Artés is prone to these episodes of would be lyricism in his attempts to pin down the meaning of his subject. “To capture the figure,” “to entrap the memory,” “to pin the body down before it vanishes forever.”

She’ll go back to the text later, she tells herself. Right now, she’s more tempted by the photographs. The book catalogues them in three broad categories: the living, the sleeping, and the dead. These categories suggest a peculiar attitude toward death, denial, and acceptance.

As she turns the pages, she finds dead people who appear to be asleep. Others with eyes open, so it’s hard to distinguish them from the living. She pays special attention to the children, held by their mothers or posed in the company of their siblings, all of whom stare straight into the camera. The eyes of the dead are wide-open. Those photos are the most unsettling, at least to her. Much more so than those in which the dead are posed as if asleep. In bed, on a divan, in an armchair: the corpse with eyes closed, in a state of lethargy or “eternal sleep,” as the book has it. Really, it’s hard for her to grasp that they are truly dead and not simply at rest.

Finally, there are the deceased portrayed as such, as lifeless bodies. Death is natural here, mundane. The coffin. Flowers. The wake and the burial. The body in repose, the body in the company of friends and family. Again, the contrast: some of the living look far more dead than the dead themselves.

As she contemplates them, she feels something pulling her in and repelling her at once. It’s not just the sordidness of it, though she knows that must be what most people find alluring here. It’s something that goes beyond curiosity. A feeling that starts in her chest and extends through her body. Sorrow. That’s the word. Grief, expanding at the sight of these children, faces sleepy, serene, mouths open slightly, fingers interlaced, little hands . . . More than once, she has to stop to take a breath.

She’s certain she shouldn’t see this, and it unsettles her to do so: these images that once were private, treasured memories intended for loved ones. To see them is to enter, almost to profane, a world of others. The feeling grows more intense as the photos become more recent, some of them taken in the eighties, in color, bringing everything into the present. It’s strange to her that this tradition continued so late into the twentieth century, so close to her own time.

She can’t help but notice the credits of the photos are all the same: the Artés Blanco Collection. She hasn’t counted, but there must be a hundred fifty of them, of diverse techniques (daguerreotype, albumin, collodion, gelatin) and origins: the majority French, but others English, American, Spanish.

She’d like to see the originals one day. Even if, as the pages turn, her dejection and listlessness have worsened. Along with a burdened feeling in her temples.

The discomfort is worst when she reaches the last page. In black and white, centered, without a caption, is the reproduction of a daguerreotype. Or so she thinks, though there’s no reference to the technique, the photographer, or the collection it belongs to. It’s a colophon, and it seems not to belong to the sequence that precedes it. Something in it makes her turn her head away. Something that disturbs her, though she can’t say what. All the elements are perfectly defined, almost saturated: the frieze of wallpaper in what might be a bedroom, the curtain in the back, the landscape over the bedstead, the glass of water on the nightstand. Everything except the figure of the deceased—or what she imagines must be the deceased, a man or a woman, a white shadow on the bed—whose body is blurry, veiled in haze. She can see, just barely, a spot over what must be the face.

The contrast between the limpid surroundings and the vagueness of the body in the bed turns her stomach, sends a bitter aftertaste up into her throat. Too many dead for one person’s eyes to see, she thinks, closing the book and leaving it on the nightstand. Probably it’s the storm, the unceasing thunder, the penetrating scent of fixer that’s gotten to her. That odor hovers all night around the bed. And the images don’t go away when she turns off the light and gets under the sheets, despite the heat. Everything is still there, and closing her eyes doesn’t help. Above all, that vaporous gray impressed on her retina, lingering like a fog that refuses to lift.

At least I don’t believe in ghosts, she thinks. Otherwise, she might feel that the photo was possessing her. This crosses her mind as she tries to sleep and the dense absence by her side steals her breath. She refuses to open her eyes and look at it. She knows it’s darker than darkness itself.

__________________________________

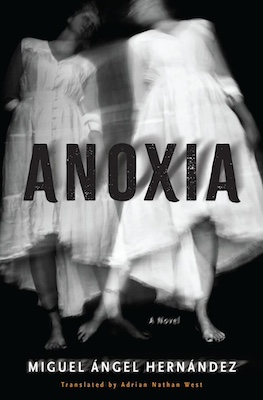

Excerpted from Anoxia by Miguel Ángel Hernández, published by Other Press on February 4, 2024. Copyright © Miguel Ángel Hernández. Reprinted by permission of Other Press.