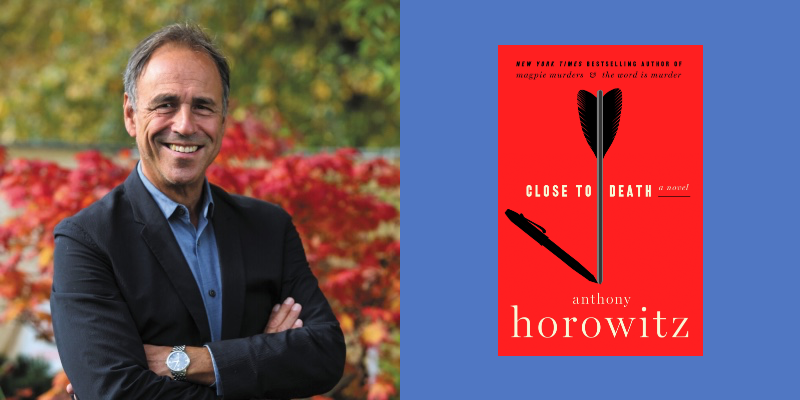

Anthony Horowitz is missing.

Not the real Anthony Horowitz, of course. He’s exactly where you’d expect him to be—hunkered down at his desk, toiling away at the next novel even as his newest is hitting bookshelves around the world.

But more than sixty pages into Close to Death (April 16, 2024; Harper) and the author’s literary alter ego—the Watson to ex-Detective Danielle Hawthorne’s Holmes—has yet to make an appearance. It’s a strange case indeed.

“I think all my life I’ve had a fear of formula,” Horowitz—whose prolific output includes the Alex Rider saga for young adults, Magpie Murders, and original works featuring James Bond and Sherlock Holmes—confesses. “I just don’t want to write the same book over and over again. So, in other words, within the narrow confines of a writer’s life, I try to be as varied as possible.”

Consequently, the fifth book in the Hawthorne/Horowitz series takes some creative liberties—the risks of which are also the rewards.

“Having done four novels in which I had dutifully followed Hawthorne, five paces behind him, making inane remarks and getting myself injured, I decided that it was time to do something a little different,” Horowitz says.

The earlier books were all narrated in first-person by the Horowitz character and chronicled contemporary investigations that he and Hawthorne, a brilliant if maddeningly eccentric PI, worked on together. Close to Death, however, utilizes the third-person (omnipresent) POV predominantly and reexamines a cold case that predates the duo’s collaboration.

“It allowed me to exercise my writing muscles,” Horowitz offers. It’s a humble assessment for somebody whose credits also include television (Foyle’s War, Midsomer Murders, Poirot), film (The Gathering, Stormbreaker), plays, and even occasional journalism.

The novel’s premise goes something like this: Riverview Close—a peaceful, tight-knit community comprised of six homes occupied by longtime friends—is set on edge with the arrival of hotshot financier Giles Kenworthy and his family, whose disrespectful antics create an atmosphere of hostility and resentment.

Then, Kenworthy is dispatched under cover of darkness by an unknown assailant with a crossbow. Nobody is sorry. Everybody is suspect. And there goes the neighborhood …

“This is a Close that exists. It’s actually ten minutes away from where I am now,” Horowitz—speaking from his Richmond office in south-west London on the River Thames—notes. “So the characters had to be realistic.”

Much like a Golden Age Agatha Christie novel, the book’s opening chapters introduce the ensemble cast (i.e., the suspects) one by one. Each is distinctly defined yet all share the same motive for Kenworthy’s demise. (It’s a bit like Murder on the Orient Express, minus the train.)

“The most important challenge of the book was to get those characters right,” Horowitz says, declaring his intent to eschew classic tropes for more multidimensional renderings and modern sensibilities. “This is a 21st Century novel.”

Meet the suspects: Master chess player Adam Strauss and his wife, Teri (who is a cousin to Strauss’s first wife); Doctor Tom Beresford and his wife, Gemma (who fashions jewelry in the likeness of poisonous animals); widowed barrister Andrew Pennington; friends May Winslow and Phyllis Moore (who own The Tea Cosy bookshop with café); “dentist to the stars” Roderick Browne and his wife, Felicity (who is mostly homebound due to a neurological disorder).

“I suppose what I was looking for was something realistic but at the same time interesting and a little unusual,” Horowitz recalls. “So what I was trying to do was mix the two together, ordinary professionals with extraordinary aspects to make characters who would be fun to follow and to suspect, any one of whom might have committed the murder …”

The readers’ suspicions reflect the characters’ own misgivings. Rather than quelling the discontent, Kenworthy’s death further exacerbates the fissures that have been growing within Riverview Close. Because as much as the residents would like to believe an outsider is responsible, the reality is that it was far more likely an inside job.

“It’s the ground zero of the murder mystery novel,” Horowitz says, likening the collective implosion to a bomb having been detonated. “It’s the moment when … it becomes impossible for that community to continue to function.”

Enter Danielle Hawthorne. Dismissed as a detective after a (thoroughly reprehensible) suspect landed at the bottom of a flight of stairs while in his company, he now works as a private investigator and is reluctantly called upon when the local authorities fail to make an arrest. Hawthorne’s methods may be questionable, but they get results.

“He is the man with no name. The man with no history. The man with no connections,” Horowitz says, likening Hawthorne’s appearance to Clint Eastwood’s arrival in a Malpaso action movie. “He is the only person in the story who does not connect to the community and who is the great first disruptor.”

In the traditional scenario, said disruptor further upsets the equilibrium only to restore order in the end. Or as Horowitz puts it: “The one whereby the detective is effectively the healer.”

That doesn’t happen in Riverview Close, however—as Horowitz discovers when he arrives on the scene to retrace Hawthorne’s steps (at the behest of his agent, who expects another book despite the fact that they haven’t worked a case since the events depicted in 2022’s The Twist of a Knife).

“In the case of Riverview Close, it’s impossible … the forces of destruction are just overwhelming,” notes Horowitz. “And that, I think, is what makes this book quite different from the other ones.”

While the set-up would seem to relegate Horowitz to a passive participant, this is but another of the story’s admirably deceptive qualities.

“In the course of the book I am actually quite active,” Horowitz says of his fictional self. “I am, in fact, doing more on my own than I normally do. Because I’m alone, I get to travel, to meet people, to ask my own questions …”

This newfound autonomy empowers Horowitz to take the initiative, even when doing so is against the advisement of Hawthorne and others. An especially impactful moment comes when he meets with Hawthorne’s former partner, who helped to bring clarity to what transpired at Riverview Close, if not closure.

“I very much enjoyed writing the character John Delaney because he is everything I want to be,” Horowitz says. “Essentially, he’s professional, he’s smart, he knows Hawthorne really well. He is part of the investigation rather than an outsider.”

And while that makes Horowitz—who is prone to self-doubts about his perceived investigative shortcomings—a bit circumspect, their eventual encounter is an amiable one. Affectionate, even, in its way.

“I couldn’t wait for that moment to happen in the book,” the author enthuses. “I can’t help liking [Delaney] because I think he is a likeable and slightly sad character, also a character who is inadvertently damaged by me.”

This rumination leads Horowitz to a surprising declaration: “I think that Dudley is a much better sidekick than I ever was. Argh!”

Readers might disagree. Horowitz, for all his foibles, is quite endearing—and his absence throughout large segments of the book makes his eventual presence, peripheral as it may appear, all the more pivotal.

“I would guess I have a bigger role in the other books even though I am less involved,” Horowitz muses. “It’s a paradox, is it not?”

This seeming contradiction is entirely fitting of the meta-aspect of the books, which celebrate the anomalous nature of the writer’s life with a wink and a nod.

“It’s an opportunity for me to have a quiet laugh at what I do and the way I inhabit my life,” Horowitz acknowledges, noting that the publishing industry is a “peculiar one” populated by rarified individuals. “I mean, there aren’t many people who spend as many hours sitting in one place as I do … There is a world outside that window, which is sort of away from me.”

And yet the sacrifice is one he’ll gladly make for the privilege of, and genuine desire to, tell stories that his readers devour for entertainment and escape.

“I love writing with every fiber of my being and I love the world I inhabit,” he says. “I’m very, very fortunate and there’s not a day that I wake up and don’t recognize that fact,”

Which is why the real Anthony Horowitz always shows up.

Just don’t tell him that sounds suspiciously like a formula—albeit one for success.