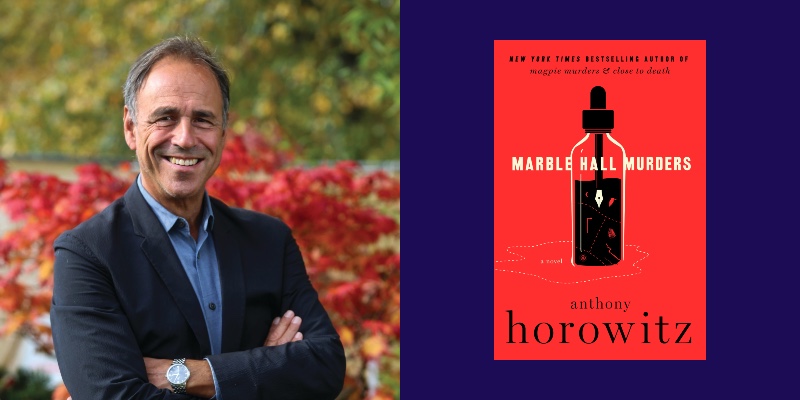

Anthony Horowitz’s biographies often state that he “may have committed more (fictional) murders than any other living author,” which may be true. Best known in the US for his work in television as the creator and primary writer of Foyle’s War, a writer for the show Poirot and the developer of the long-running Midsomer Murders, Horowitz is also the writer of the young adult Alex Rider series of novels. In recent years Horowitz has been focused on writing novels, including two Sherlock Holmes books, three James Bond novels, the Hawthorne series of mysteries, of which there are currently five, and the trilogy that began with 2016’s Magpie Murders and concludes with the new novel, Marble Hill Murders.

Magpie Murders was a celebration of the mystery novel, but also an examination of the genre. Each of the three novels in the trilogy are about a novel within a novel and about the secrets encoded in the text, but each has a different structure and approach. This is not surprising because for all the murders he’s written, and as serious and prolific as he is, Horowitz is very playful in how he works. He’s constantly trying to go out of his way to find new ideas and structures and approaches. To both check every box that people would expect, but also subvert their expectations. Foyle’s War involved a murder (or many) in each episode that was resolved, but it was primarily about the experience of the Second World War. The TV series New Blood was a mystery thriller about white collar crime and corruption, but also a look at the life of 21st Century immigrants in Britain.

The new novel has, as Horowitz admitted, a somewhat unusual origin. On the last day of filming Moonflower Murders, star Lesley Manville “mentioned that she would love to do a third season and of course everyone was excited by the idea. Unfortunately, there was no third book ready to adapt for TV. Therefore, after a bit of thought, I sat down and wrote Marble Hall Murders which I finished in six months, and then, one day later, began the TV adaptation.” The third series is in production and Horowitz – who á la Alfred Hitchcock likes to cameo in his shows – was kind enough to answer a few questions.

You mentioned that wrote this book in six months. Is that typical for how and how fast you write a novel?

Absolutely not! Magpie Murders took five years to think up and fifteen months to write. I had to write Marble Hall Murders extremely quickly because PBS/Masterpiece and the BBC had greenlit a third TV series and I needed a novel to adapt. The writing process was challenging, to say the least – but I’m surprised and pleased that it came out so well.

One reason I ask is because you’re very prolific, but you’ve spoken about Magpie Murders having a long gestation process. Was that the exception for how you’ve worked over the years?

It often happens that an idea will come into my head and stay there for years and years until I realize that the only way to get rid of it is to write it. There are three ideas like that in my head right now. Nightshade Revenge, the most recent Alex Rider book was based on an idea I’d had almost twenty years ago.

You’ve written a lot for television and film. When working with someone like Michael Kitchen or David Suchet or John Nettles over time, outside of any ideas or suggestions they may have, I assume that their acting choices affect how you write those characters. Has Lesley Manville affected how you’ve come to write Susan?

Susan Ryeland was originally based on two editors I’d worked with (both women). But of course I can’t write the character now without thinking of Lesley Manville who has appeared in two seasons and soon will be seen in a third. That’s the joy of working in TV. Lesley doesn’t make direct suggestions but watching her on the screen, I see things in the character which I hadn’t noticed before. I also understand, intuitively, the sort of dialogue she favours. And inevitably that influences the way I write.

When you adapted Magpie Murders to television, you completely rethought the structure and the storytelling choices. To a degree that was stunning. But you take great care to structure the books in very literary and novelistic ways. And to structure and design each book differently. You want them to be novels, is that fair?

When I was writing Magpie Murders, I realised that it would be impossible to leave Susan Ryeland out until half-way, as happens in the book. It would utterly waste the talent of our star, Lesley Manville. So I was almost compelled to bring the past and the present together, to have Pünd and Susan on the same page. It was a terrific breakthrough! As for the books, structure is essential. We have two, perhaps three timeframes and a large cast. If I don’t know where I’m going, nor will the reader. The key word in your question is “differently”. The main challenge is to use effective the same idea – the book within a book – but to do it in a way that isn’t repetitive. I have a fear of formula.

Even as you’re figuring out how to tell the story in Marble Hall Murders, are you also thinking about how the TV version would play out? How much are you adapting the story at the same time you’re writing it?

I try not to. When I’m writing, I’m immersed in the story, the characters, the atmosphere. I’m not sitting back, thinking about a book that has to be adapted. And I can’t let one inform the other. For example, I decided to set Marble Hall Murders – the book– in the South of France. I knew from the start that it would be too expensive to film there and that I would probably have to rewrite an entire strand – the theft of impressionist art. But I went ahead anyway. That was how the book has to be.

In this novel we have a new version of Pünd and what was important that would be in this version of Pünd and what did it have to be missing? How were you thinking of these as opposed to the Conway books we read in the first two?

I’m not sure that Pünd’s character has particularly changed but of course the circumstances have, as Alan Conway is dead and he has a new author in Eliot Crace. This has perhaps made him a little more aware that he is, at the end of the day, a character in a book and I’m very fond of the trick we pull off at the end of Episode 5 when reality hits in a particularly shocking way. I’d say more but I don’t want to spoil the surprise.

You’re clearly not opposed to continuations and sequels, but beyond the ones that you’ve written, are there any that you think were especially good, either because they were so good at being like the originals or because they managed to change or reinvent them in interesting ways?

I’m not at all opposed to continuations and sequels but I’m ashamed to admit that I don’t tend to read them myself. This is not a deliberate choice – it’s just that I have so much to read (I love nineteenth century fiction) that I just don’t have the time.

The Pünd books are all about anagrams, hiding information in them for people to hunt down. I’m curious what you think about these mysteries and thrillers which are all about puzzles and hidden clues, often tracing conspiracies and buried secrets, because they are related to traditional mystery novels, but they’re also their own thing that I think of as very influenced by video games and their storytelling.

I’m certainly not influenced by video games. In fact, I started hiding things in books long before video games were invented. It started with a Robin Hood novel, tied in to a hugely popular TV show which I’d been working on. I did it as a favour but I found the work quite dull so I concealed the names of all the actors and production team inside the text as a sort of private joke. That’s what Alan Conway does too – but he’s more malign. I like the idea of puzzles and anagrams because they remind you of the building blocks that make up a story – i.e. the words.

You’ve been focusing more on fiction in the past 15 years. Magpie Murders has become a contemporary classic. In that same period, I would argue that your adaptations of Magpie Murders and Moonflower Murders have been some of your best screenwriting work. What are you thinking about or wanting to do next? More Hawthorne novels? A new TV show? A new novel? Something completely different?

I have lots of thoughts and perhaps not too much time. I’m currently writing the sixth Hawthorne novel and plan to do twelve in total. I’m talking to my wife, producer Jill Green, about a possible TV series for Hawthorne, although we have to find a way to make it original, to make the meta-fiction work on the screen. I have ideas for two murder mysteries set in very unusual locations: one in the nineteenth century. I want to write another play. I’m always looking for ideas that tear the envelope. The danger of writing so much is that you become repetitive and formulaic.

Is there any chance of more Foyle’s War? Or a sequel focused on Sam? I apologize, because I feel like you’re going to be asked this until the end of your days.

I’m afraid there’s almost no chance at all. I worked on Foyle’s War for sixteen years and that’s enough. Also, I don’t like going backwards. But I’ve learned never to say “never” about anything.

So if Lesley Manville says during the filming of Marble Hill Murders, this has been such fun, Anthony…will you take that as a challenge or will you say, why don’t we do something else together?

I would work with Lesley Manville again like a shot. But we have always seen Marble Hall Murders as the end of a trilogy.