The hospital bed was hovering a foot above the floor. Fred Sjöström had been floating around in a kind of dreamlike, hallucinogenic state for days. Maybe weeks? He didn’t know. He had vague memories of being transported through corridors. White tunnels that never seemed to end. Bright ceilings rolling by high above him. Spinning every time they turned a corner. Bare walls. Diffuse shadows cast by people in white coats that floated past.

Then the pain. During his years abroad, he had endured enormous physical pain. Wandered through scorching deserts, slept outside in subzero temperatures in cold, damp clothes. Lived with open wounds that wouldn’t heal, even been shot. Unspeakable pain. And still that was nothing compared to what he was going through now. The pain that had washed over him when he woke up felt like electric shocks pulsing through his body. His legs were the worst. Last night, he had woken up and screamed until a nurse came in and gave him even more morphine.

He looked down at his body. He had seen torn-off limbs and truly gruesome wounds as a soldier, but what was hidden under his own covers knocked the air out of him. Everything was gone. His feet. Ankles. Calves. Knees. They had clamped two big white tubes onto his upper thighs. They looked very strange. Like two shapeless lumps of plaster. So heavy he couldn’t move them so much as an inch. And then the pain. How could nature have set things up this way? What was the point of feeling pain in body parts that were no longer there?

Everything was gone. His feet. Ankles. Calves. Knees. They had clamped two big white tubes onto his upper thighs. They looked very strange. Like two shapeless lumps of plaster.At the moment, the morphine had him numbed. His sinewy arms lay like heavy logs along his sides. He could turn his head a bit, but lifting it off the pillow was impossible.

A lot of people had been in and out of his room. White coats wandering in and out. Doctors with concerned looks on their faces. A few men in dark clothes had been by as well. At first, he hadn’t understood who they were. They had demanded information. Asked questions about who he was and what his affiliation was.

A counselor had been there, too. Her voice was calm. Pleasant. Almost dreamy. Her words had been comforting. She had talked about his condition. And his illness. The diagnosis he didn’t want to talk about.

He had known for a long time that something was wrong. He had lost weight and had a hard time eating. His usually strong, robust body had come up short for the first time ever. After collapsing at work, he had been taken to the hospital in an ambulance. That was when he was told. Pancreatic cancer. Stage three. Surgically removing parts of the gland was pointless since the cancer had been discovered too late and had already spread.

Fred had received the news in silence. Just stared vacantly into space. The doctor had repeated the diagnosis. Told him he was going to explain it several times, as many as Fred needed to grasp the implications of his disease. Fred had grasped it the first time, but hadn’t been able to think of anything to say. In the end, he had calmly held his hand up and nodded to the doctor to show that he had understood. Then he had left the hospital.

He had made up his mind that day. Known what he had to do to give his life meaning, despite everything that had happened. He wasn’t going to let the illness kill him; he was going out on his own terms. With a message. He had nothing left to lose.

Talking to the counselor about his disease was pointless, but he liked her presence. He had heard a nurse tell the others that his blood pressure was lower after the counselor’s visits. That his breathing was more regular. Her calm voice had given him a feeling of harmony that he couldn’t remember ever having before.

He thought his war years had prepared him. He and his comrades had laid down their bodies, their lives, for what they believed in. Or to get away from their previous lives. They had all had their own reasons for joining up. Some had done it for a higher power, or to feel alive. Because even though he knew he might not survive the war, he had felt strong. Immortal.

Living close to death made you feel more alive.

He had been ready to die. But that was then and there. What he was going through now, no one could ever be ready for.

The only thing that made him feel better was that he didn’t have long to go. Soon, everything would be over.

The room to his door had opened. The hinges squeaked. The sound hurt his ears. Metal against metal. Lifting his hands up to cover his ears was impossible. Just opening his eyes was an effort. He raised his eyebrows as a first step, in the hopes of making the next step easier. His eyelids covered his eyeballs like twoton blast barriers. He gave up. Let them stay closed. Focused on his breathing instead. His lungs. Oxygenizing his blood. That was important. Slowly. In. Out.

They had removed the respirator. Ever since, his throat felt scratchy and dry like sandpaper. He tried to clear it. In his weakened state, it turned out to be impossible.

Just like the night before the explosion, he felt separated from his body. As though he were someone else. Someone standing next to himself, observing. Noting his suffering. His desperation. His disappointment at still being here. Being conscious. And yet, sometimes he was unsure if he really was.

The footsteps walking over from the door were light and unlike the other ones that had moved through his room, these feet wore high heels. They fell silent at the foot of his bed.

“Fred Sjöström. My name is Leona Lindberg.”

From somewhere, he found the strength to push his eyelids up. He studied the woman in front of him. Once he managed to focus, he saw a pair of weary eyes looking back at him.

“I’m a detective with the Violent Crimes Division. I’ve been ordered to come here to interview you.”

So this is what she looked like. Leona Lindberg. He didn’t know what he had expected, but it wasn’t quite this. Half her face was illuminated by the light from the window, which made the other cheek look ghostly pale. Her dark, unkempt hair seemed to have a mind of its own. He mused that the combination of such dark hair and pale skin was unusual. She was young, probably around thirty, but still looked haggard somehow.

He’d been unable to speak, had only barely had the strength to hold a pen, to scribble a few words on a piece of paper for the men from the Security Service. “Will only speak to Leona Lindberg,” his note had read. He had been unsure whether her surname was Lindberg or Lindblom, but now she had confirmed that he had got it right.

“I have no interest in dragging this out and hate hospitals to boot, so you’ll be doing us both a favor if you continue to refuse to talk. Then we don’t have to waste each other’s time.”

He continued to study her. Her eyes were darting around the room. Seemed to be taking in the tubes, racks, and machines around him.

“I have a duty to inform you that you are still charged with committing a terrorist act of causing devastation endangering the public outside the east wing of Parliament on 30 May at 1:55 p.m. You have a right to legal representation during both the investigation and at any subsequent trial. Do you have a lawyer in mind?”

“I have a duty to inform you that you are still charged with committing a terrorist act of causing devastation endangering the public outside the east wing of Parliament on 30 May at 1:55 p.m.She paused, waiting for a reply. He made an attempt to speak to her. Tensed his stomach and his lungs, but the only thing he managed to get out was a noise that sounded more like a faint clearing of the throat than a word.

“If you don’t want to communicate with me, that is, as mentioned, perfectly fine by me,” she continued, and picked up the purse she had placed on the floor by the bed.

He made another attempt at speaking.

“I am in fact obligated to inform you that you have the right to remain silent during this interview, if you so wish.”

He did his best. Dug in deep. No sound at all this time. A wave of darkness and anxiety washed over him. He was unable to move. To speak. He wanted to scream but couldn’t summon the strength. He was trapped inside his own body.

She slung her purse strap over her shoulder and started walking toward the door. He gave it everything he had.

“You . . .”

His voice disappeared. But she had heard him. Turned around. Looked at him with a frown. Walked over and leaned in closer. He didn’t try again until her face was mere inches away. On his next exhalation. He breathed in.

“It’s . . . you . . .”

New breath. One more. He braced himself again.

“. . . est sacrée.”

She stopped and studied him before turning around once more and leaving the room.

__________________________________

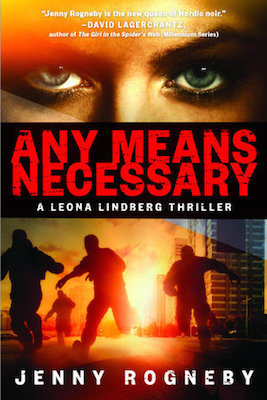

From ANY MEANS NECESSARY. Used with the permission of the publisher, Other Press. Copyright © 2019 by Jenny Rogneby, translation copyright © 2019 by Agnes Broomé.