“Going down the steps with a gun in his hands”

Our family’s criminal history used to be a secret. Before Google, it was easy to hide your past.

When my grandmother Effie Satterwhite was 17, she had a boyfriend named Jim. According to her brother’s court testimony, he once caught them “conducting themselves in what he thought a very unbecoming manner on the front porch.” He ordered Effie inside, and told Jim never to come back. But Jim declared he wished to marry her.

A few months later, when the young couple returned from a date, Jim tried to kiss her, but Effie pushed him away. When the town clock rang eleven, Jim said he had to go. This time she did let him kiss her.

Once inside, Effie saw her father run down the porch stairs with a shotgun, then heard a shot. She tried to run to Jim, but her father shouted at her, telling her she had gotten him into trouble with her hugging and kissing.

My great-grandfather appealed his conviction, claiming Jim was trying to seduce his daughter. But the jury found the two intended to marry, and his appeal was denied.

When I discovered this secret via an idle Google search, it softened my judgement of my judgmental grandmother. She didn’t marry until she was 33, old-maid territory in 1921. Her husband probably didn’t know about the murder, and her children certainly never did. In speaking with other descendants of my great-grandfather, it’s clear the family blamed Effie for her father’s actions.

As a writer, Effie’s experience reminds me that characters are the way they are because of something that has happened in their pasts.

“A dangerous member of a gang of organized incendiaries”

After discovering the truth about Effie, I searched for my maternal grandfather: Barney Clowers.

Barney shows up many times in Newspapers.com. Holding a gun on his employer, charged with assault with a deadly weapon, sued for divorce by his wife, Nora. But he was best known as an arsonist.

After the sawmill where Nora worked as a cook (in the aptly named Forest, Washington) burned down in 1919, one of their daughters signed an affidavit placing the blame on her estranged father.

At the time of his arrest, Barney was believed to be a member of a Pacific Coast arson ring. Various fires were laid at this gang’s feet, including the fatal Lincoln Hotel fire in Seattle. But when I requested his prison records, they said he had burned down the sawmill to get back at Nora for leaving him.

After being released from prison, Barney was found on the street, unable to identify himself. He was declared insane and carted off to an asylum, where he soon died. (The only photo I have of him is from his commitment papers. He’s smiling.)

When I’m writing, I think of how the people closest to you may cause the most damage. In the book I’m working on now, In the Blood, a girl’s biological father is willing to do almost anything to get her attention.

The marshal who rode for Hanging Judge Parker and then was hung himself

My great grand uncle Shepard Busby, who once rode as a deputy marshal for Hanging Judge Parker, loved the ladies a little too much. He got married in 1858, 1860, and 1868 (likely without divorcing any of them) and had children with at least one other non-marital partner. But finally in 1891 his chickens came home to roost, and another marshal was dispatched to arrest him for adultery.

Instead, the arresting marshal was gunned down by Shepard, who was quickly captured and sentenced to death. But on the hanging platform, the hangman discovered he and Shepard were both members of an organization for Union Army vets. He refused to hang him. Shepard must have thought his luck had turned—but another hangman was quickly found and carried out the sentence. This event was memorialized on Shepard’s tombstone.

Even cops sometimes turn out to be criminals, an idea I explored in the Edgar-nominated The Girl I Used to Be.

A head in a sack

My third great-grandfather, John Clowers, was murdered in Missouri in 1868. That much the many descendants of his sixteen children agree on. Family lore says he was murdered by a group of men, and that those men were killed in turn by some of his adult sons. Most of the stories involve decapitation.

Bob, an elderly descendent I spoke with, said my great-great grandfather and Bob’s great-grandfather were two of the revenging sons. In fact, he claimed his great-grandfather had fled Missouri carrying the head of one of John Clowers’ killers in a sack.

At first I was enthralled. It sounded like a Tarantino movie. But then I realized it had to be a tall tale. If you were fleeing a murder scene, carrying around the victim’s head would be a red flag. Plus a head would eventually stink, while taking up space that could be used for something more useful. I wrote off the story.

But then Bob told me that when he was a child in the early 1940s, his great-grandmother had used a human skull as a door prop. And if anyone inquired, she would say it belonged to the man who had killed her father-in-law.

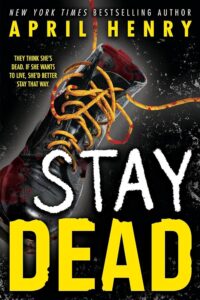

Blood is often thicker than water, and a character might go to extraordinary lengths to avenge a parent’s death—just like my character Milan in Stay Dead.

Pig bewitchment

In 1657, my ninth great-grandfather, William Meeker, was accused of being a witch, after his neighbor decided witchcraft was the reason his pigs were dying. How did he know this? “He did cut of the tayle and eare of one and threw into the fire,” which he claimed was “a means used in England by some people to finde out witches.” He formally accused William of bewitching the pigs to death.

About one-third of people charged with witchcraft in what later became Connecticut ended up being hanged. Luckily for me and for William, he was acquitted of all charges.

You can’t always trust what people claim to have witnessed, an idea I explored in Girl Forgotten.

And while I am descended from murderers, an arsonist and possibly even a witch, I would never do any of those things in real life. But I would totally put them in a book.

***