Are villains the most important characters? That’s a crazy question. It’s also click-batey and nigh on ridiculous.

Or is it?

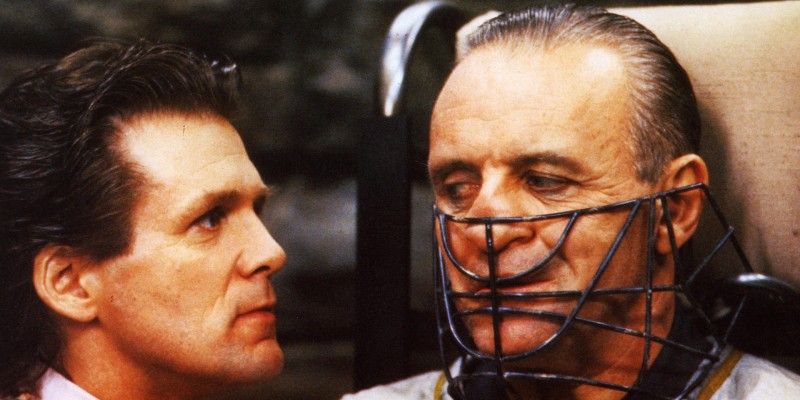

Villains are the characters we love to hate but secretly we hate the fact we actually kind of love them. It’s the same reason why some women date the bad boy biker but eventually marry the cost accountant. It also explains why Hollywood festooned Dr. Lecter’s banquet of abominations with five Oscars but blackballed Disney’s sweet-natured animated classic, Beauty and the Beast.

I write for the Oregon Files, one of five series in the Clive Cussler universe. If you know anything about Clive’s world and especially the Oregon Files, every story is centered on the main protagonist. In the Oregon Files, Juan Cabrillo is the first among equals in a heroic collective of special operators, technical geniuses and unapologetic patriots. So how in the world could villains be the most important characters in any of my stories, including the upcoming Quantum Tempest?

Well, there a bunch of reasons to make that claim. But let me start by saying that villains are without a doubt the most important characters of any story when the writer builds the story. They are also the most important characters to sustain the story to its final conclusion—and sometimes beyond. I’ll make my case by explaining why great villains are so important to the story-creation process and then I’ll lay out my process for building great villains.

WHY WE NEED GREAT VILLAINS

There are at least four reasons why we need great villains to build our stories.

First, let’s get back to basics. All stories are driven by conflict. No conflict, no story. A conflict means somebody wants something but an obstacle prevents them from getting it. That’s Creative Writing 101.

In most stories, the primary obstacle is the villain. The Greeks taught us that. They even gave us the terms protagonist (“the first to fight”) and antagonist (“the one who fights against”) to prove that point. Case closed.

Or is it? In most genres, including my own, who is actually the “first to fight?” Isn’t it the villain? In storytelling, the villain is almost always the true “first mover” of the story because they almost always take action first. The villain is the one who tips the hero’s world out of balance. This catalytic event is when the story actually begins. This means villains are “doers” with energy, vision and drive—just like every great heroic character. And because villains seize the story initiative, it means they begin one step ahead of our intrepid heroes and stay there until the very end which itself becomes another level of conflict.

In short, no villain equals no conflict which equals no story. And guess what? Great villains create great conflict.

Second, the story is only as great as the villain. Why do I say that? Doesn’t the greatness of the story reside in the hero? Yes…and no. How much energy and passion and sacrifice and endurance must our hero expend to overcome a near-sighted, bedridden, quadriplegic octogenarian with only days to live?

No doubt, Juan Cabrillo is an iconically heroic character but no matter how great Cabrillo is, he can and will only rise up to the level of the overwhelming challenge he faces. In other words, great villains bring out the greatness in our heroes.

Third, it’s the villains, and not the heroes, who determine the stakes of the story. Our heroes will only choose to rise to the perilous occasion of the desperate conflict because the stakes are perilously high. It’s hard to imagine a compelling villain chasing a five-dollar discount on an oil change as the stuff of great story. But nuclear war? Global plague? Total financial collapse? These are the apocalyptic “pulse-pounding” dust-jacket thriller stakes that drive our heroes into hazard’s arms, risking life and limb to forestall the ultimate catastrophe. In the end, the villain’s stakes are the hero’s stakes, too.

In Quantum Tempest, my villains want to acquire an imminent technology that will allow them to dominate the rest of the planet and change the course of history for the next five hundred years. It’s an epochal struggle, and a very real one our world currently faces. My novel explores the dire consequences of Juan’s failure to stop the villains in their tracks because real villains in the real world are pursuing the very same dangerous objective.

Finally, great villains sometimes teach us the best lessons. We learn a lot about how we should live and move in the world by inculcating the actions and attributes of our heroes. But there are always secondary and important lessons to be drawn from the villains. Why? Because villains reveals the demons within us. Could it be that our desires are actually “monstrous” though well-intentioned? Is it possible our well-intentioned motivations are fueling murder and mayhem?

In Quantum Tempest, you’ll encounter a band of brilliant but murderous terrorists known as the Guardians. What you’ll also discover is that they ruthlessly slaughter certain people because they want to save the whole of humanity. Is there a lesson to be learned there? You betcha.

HOW TO BUILD GREAT VILLAINS

First, the most important rule is this: Every great villain is the protagonist [“first fighter”] of their own story. You can’t write a great villain if you don’t acknowledge this point of view, no matter how twisted their motivations might be. As a writer, it’s altogether natural but far too easy to focus solely on the hero. But in so doing, the villain merely begins to react to the actions of the hero. When that happens, the villain loses energy, focus and, worst of all, any threat they pose as their actions recede into inevitable passivity. Your best villain strikes first, strikes hard, and keeps throwing the relentless haymakers that keep your hero ducking and sweating and bleeding, page after page. To do that, you must take some time and re-tell your entire story from your villain’s perspective. Trust me on this: Your story will be better for it, and you’ll find new chapters and story opportunities you never saw before.

Piggy-backing on that last point, the next step to building a great villain is to create a fully realized character, the same as we do with our protagonists. Unless we’re talking about an AI or some other non-human antagonist, we’re talking about people who had parents, an education, a background, a culture. There must be “great” (and ideally, “greatly terrible”) reasons for why they do what they do. By making the villain’s evil fully compelled, we make the villain and our story more fully compelling. Just as the hero risks everything to stop the villain, so, too, does the villain risk everything to achieve their villainous desires. Make it make sense.

In prepping my writing for Quantum Tempest, I developed character sketches for all of my principal villains: psychic wounds, broken dreams, festering scars, you name it. I know exactly why my villains did what they did, but sometimes they did it in ways that even surprised me!

Third, for a thriller story to make sense and hold our interest—no matter how “over-the-top” the setup might be—the reader must have the confidence the villains are acting rationally. “Rationality” is classically defined in economics as utility-maximizing behavior. For the rest of us, rationality simply means someone has a set of goals they want to achieve, and they prioritize those goals, and chase after them accordingly.

The very best villains are entirely rational. But they really, really want something and must always want it and won’t let anything else take precedence over getting it, including morality and virtue and anyone or anything that stands in their way of getting what they want. In other words, great villains have insatiable and monstrous desires. (You could even argue it’s their monstrous desires that make them villains.) Their “want” and especially their “need” are always destructive and utterly twisted or corrupted or vile from our hero’s perspective. But their villainous desire must be so great they are willing to do anything to achieve it—including destroying our valiant hero.

Fourth, and I’ve already alluded to it, the great villains have extraordinary powers—greater powers, seemingly, than even our hero. Of course, it’s possible for two evenly matched opponents to make for an interesting contest. But my favorite stories are the fights where the good guy seemingly has no chance against the villain. Underdog stories like David and Goliath, Thermopylae and Agincourt thrill us because they deliver an unbelievable triumph for our heroes, and more importantly, for the virtues that make our heroes truly great arise because of—not despite—the overwhelming odds. That’s also why I like to have more than one villain to outnumber the hero, and my villains are always in competition with each other. Why? More conflict! And more story opportunities.

So, if a great villain is overwhelmingly powerful, how can the hero possibly win? Or put another way, how does a writer build a rock too heavy for the hero to lift—and then get the hero to lift it? The short answer is that the great villain is very powerful…maybe ALMOST too overwhelmingly powerful, so all the great hero can do is draw upon those resources the hero does possess within themselves that eventually (and barely) transcend the external power of the villain.

And herein lies the theme of every story. By watching the hero draw upon their own internal resources, the reader asks themselves, What resources can I draw upon from within myself to overcome the challenges I face?

In the case of Juan Cabrillo, he begins by drawing upon the incredible technological resources of the Oregon and her valiant crew. He can also draw upon his own power of improvisation in the heat of battle, his vast physical stamina, and in extreme circumstances, pull out a pistol or a block of C4 from his artificial combat leg. Ha!

But for the sake of us mere mortals, Cabrillo relies on none of these things to win the final battle. Instead, he draws upon his sense of justice, his courage, his love of his friends, and his willingness to sacrifice himself not only for the greater good he’s fighting for but also for the lives of his people—and trust me, “self-sacrifice” is not on any great villain’s agenda.

In a word, Juan often lacks the external brute force power he needs to defeat the bad guys. But he can and does always draw upon the soulish virtues that make him a great and timeless character to ultimately win the day—the same virtues we all possess if we will but deploy them.

It’s these greater spiritual and moral virtues the hero possesses that the great stories must convey to us if we want our civilization to survive. We are only as just or as wise or as brave or inventive as the stories we tell ourselves. Stories are the software that programs the cultural mind. That’s why stories matter. Great stories matter even more.

Hopefully I’ve proven why we need great villains to elevate our stories to greatness. Great stories are even more critical now that the barbarians—literary, political, spiritual—are not only outside the gate but rampage within the walls of the city itself

And truth be told, that’s what’s really at stake in Quantum Tempest.

***