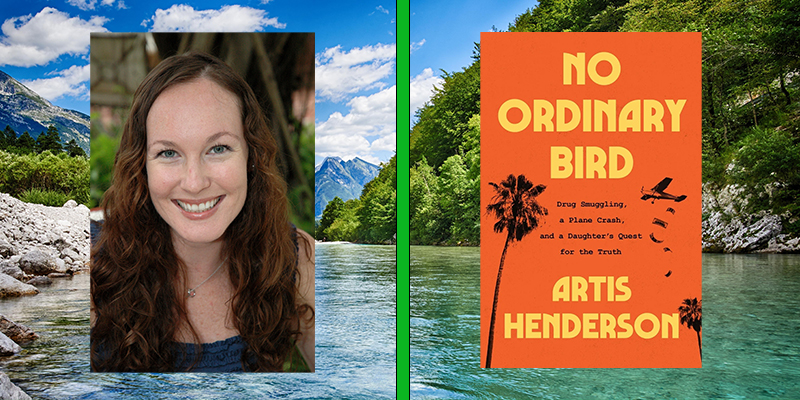

Artis Henderson is an award-winning journalist who has written extensively about conservation, the natural world, and human beings’ relationship with the wild for National Geographic, The New York Times, Sierra, and other publications. Her new book is very different. No Ordinary Bird: Drug Smuggling, a Plane Crash, and a Daughter’s Quest for the Truth is one part true crime saga, and one part biography of a poor Georgia farmer turned pilot turned multimillionaire drug runner who was killed in a strange plane crash– Henderson’s father.

Henderson was five years old and in the plane crash that killed her father, and nearly killed her. As an adult she looked into the years leading up to that crash, reconstructing the life of a man she remembers only a little. In the process she visited a man in witness protection, looked into ties between the Bahamian government and drug smuggling in that era, the Iran Contra affair, and the CIA’s ties to smugglers, the islands her father bought– one of which used to be owned by a nazi sympathizer who used it to refuel U-boats. It is a wild and larger than life story, but that’s not all it is. Henderson went back to Georgia where she grew up and met people for the first time since she was little, people who remembered her parents, the half-siblings she never really knew. Reconstructing her father’s life, she was forced to consider that her father was likely murdered by the US government. Henderson spoke with me recently from Perth, where she has been researching a new book, to talk about meeting her father’s old friends and colleagues, the strange world that is the 1970s, and the non-answer she received from the CIA and FBI.

Alex Dueben: This is your second book, but in the context of your life, when did you start writing? How did this become your life?

Artis Henderson: My whole life I wanted to be a writer. Forever and ever and ever. When I was a kid, I remember drawing a picture of a check that I got from a publishing company. It was for $12.

Which seemed like a fortune.

Exactly! [laughs] I was always writing. Always, always.

You’re a journalist, so much of your work right now and for years now has been writing about conservation, about environmental impact. In this context, what made you go, I should look at my father?

I think books are about obsession. I’m not sure if it’s the same for novelists, but I imagine it is. For me, it’s the thing that I can’t get out of my head. Certainly my first book was that and, and this book became that. Though I was resistant to it for a long time. There was a woman I mentioned in the book—La Venier Mize, a talented young reporter when my dad was alive who covered his story. She reached out to me in 2015 and offered to share some things about my dad and his life. I responded by email and said, I don’t really want to talk about that.

Which is crazy to me now! Especially because my approach to life is always to say yes. I say yes to a lot of weird things, but I said no to that. When I reconnected with her through the reporting process of this book, she was like, you didn’t want to talk to me in 2015. I went back through my email archives and I found her message. I was shocked. I generally have terrible boundaries, but for whatever reason, in that moment, I was firm. I was still very resistant to my dad’s story. It took me a long time to be able to talk about it.

I’ve written two books now, and I’m coming to terms with my process. First, I write a really bad novel. [laughs] That’s the first two years. Then for the next two to three years, I interview other people who did similar things. My first book, the second iteration after the bad novel, I interviewed military widows about their stories. I asked them the questions I couldn’t ask myself, the things I couldn’t stand to look at in my own story, like autopsy reports. Eventually it got to the point where I realized I couldn’t tell the story I wanted to tell through these other women’s experiences. I could interview them forever, but I’d never get to the emotional truth of it. I could only do that by telling my own story. For this book, after the bad novel, it was two to three years of interviewing drug smugglers who didn’t know my father at all and asking them what it was like. Eventually, it got to the point where I realized that wasn’t the story I wanted to tell. I wanted to tell my father’s story.

I understand that approach, though. As a journalist, every publication wants a personal through line to a story, so you have that obsession and then you build elements of the story around that. You realized in the process of writing that, no, this isn’t the story.

Yeah, exactly.

No Ordinary Bird is about many things. It’s about drug smuggling and the logistics of that. We’re the same age, and it’s about how the seventies feel like a whole other world.

That’s so true.

It’s also a book about an adult getting a different perspective, many different perspectives, on the father you never really got to know.

Thank you for seeing that. To have this person who disappeared from my life, from age five onward, and then to suddenly both discover him, and then re-lose, was very hard. Because not only did I learn about the drug smuggling, but I learned about my dad as a person. People liked him. He was a good dad to me. I think he really loved me. These were things I didn’t fully know.

Part of that absence is not just moving, not just your mom not talking about him, but she cut off contact with family and friends. And you have that conversation with her when she says, that was to protect us.

Yes! And that was so late in the process of the book itself. I already had the final, final manuscript. It was so hard to have that conversation with my mom because that wall around her is just so thick. Over the course of this book, we had talked about my dad a lot, and she had opened up about him more than she ever had, but that was the final missing piece. It explained so much about who she is and how we lived. I’m still not over it.

That was at the very end of the process of writing this book? Wow. You don’t talk much about like how you grew up afterwards, but that scene explained so much.

I understood things differently after that conversation.

Some of the book is just about you coming to learn about your father as an adult, which we don’t all get to do, but it is a different experience and a very emotional experience. I wondered what it was like meeting all these people, or meeting them for the first time since you were little, and that process.

I’d love to answer that, but before that, I was going to ask you a ruminating question. I wonder if this process of discovering our parents when we’re adults—do we have more grace for them? More grace than if we grew up with them? I think I have a lot of grace for my father in this book. But it’s complicated, right? Our relationships with our parents.

I think so, but I think our relationships with our parents are always complicated.

Yeah. But meeting all those people whose names I’d heard whispered in conversations and then getting to meet them in real life—it was like a homecoming. Though I should have started this book five years earlier because so many people passed away in the writing of it. I’m so glad I got to meet everyone I did.

It was interesting when you went back to Georgia and the response of the people there, who were happy to see you, but there was this myth around your dad and half the people not believing he died.

I know. I think I brought some disappointing truths because there were so many good stories– that my dad was still alive in witness protection, that I had climbed out of the plane and run to the road and signaled for help, that there were gold coins hidden all over our property. But who knows? Maybe they don’t believe me, and that’s ok too.

It’s easy to laugh at the idea of his death was faked, but your mom and everyone around your dad thought that he was a great pilot and there’s no way he would have crashed like that and the crash report made no sense. No one believed it was an accident.

Yeah.

When you asked the government for answers and they gave you the Glomar response– “we can neither confirm nor deny”– did part of you think that’s what you would get before you even sent in the request?

No. I didn’t. I think I was a little bit naive. I had never filed a Freedom of Information Act request for any of my stories, but as a journalist I knew about it. My early hope was that a box would be delivered and inside would be all these files about my father, the secret agent. I’d be like, I found it! Here it is, world! I’m embarrassed to admit that now. [laughs]

Also, it’s decades later, Iran-Contra is public knowledge, they’re covering up everything about this one guy, so then what isn’t secret? I mean the FBI sent you a photocopy of a newspaper article? They’re trolling you!

I know! They sent a letter where almost everything was redacted. I was like, they’re punking me, right? Why would you even send this?

I was impressed that your half sister filed a FOIA request for everything when she was a teenager. That’s impressive.

Right? I saw the date and I was like, wow. My sister! I mean, how bold is she? I’m so proud of her.

Because they said, we can neither confirm nor deny– which as you point out, is not their standard boilerplate answer to every inquiry– you don’t have a definite answer. If you were writing a novel, you could do whatever, but how have you been sitting with not having an answer and knowing you’ll likely never have an answer?

I think that not having a definite answer about my dad’s death gives my brain a small safe space to believe that my father was not murdered. The evidence is so overwhelming, but I think if I really believed that, to my core– how would I get up every day and just go about my life? I mean, I know it happens. People are murdered and their children have to go on living. I guess we just do it, right? But not having that definite proof is just a little bit of safety for my heart, I guess. Is it better that way? Is it better not to know? I don’t know.

Was there a point in the process later on where you were like, I should have just written this as a novel. This would be much easier as a novel.

[laughs] No. I have an MFA in fiction. I know I’m a terrible novelist.

But if I did write it as a novel, my dad absolutely would have faked his death, fled the country and still be alive in the Bahamas. That would be the novel I’d write for sure.

The book ends with you and your siblings. You’re closer now than you ever were. That conversation where they tease you about, are you an only child or do you tell people you have siblings? You touch on this idea that both things can be true at the same time.

Yes, exactly. Both things are true at the same time.

It’s been a gift, having us all together in this way that I don’t think we really were before. My brother, Terry, especially. Without this book, I would never have known him the way I do now. Having him in my life is amazing.

Your first book was a memoir and so there are ways that you’re prepared for what writing a memoir entails as a writer and what it involves emotionally as a person having gone that before. Did it prepare you for writing this book?

[laughs]

Readers are not going to be able to see just how long and hard you’re laughing at this question. [laughs]

I have this writing group. There are four women and we’ve known each other for a long time. We wrote our first books together. They were there with me for the journey of the first book. When I started this book, I gave them early pages. One of them said to me, there’s not enough of you in this. I remember I looked at her and said, oh my god, am I writing another memoir? They all laughed and they were like, yeah, you’re the only one who doesn’t realize it. I was like, no, no. I fought it for so long. It’s brutal to write a memoir. I don’t know why anyone does it. [laughs]

You were originally thinking of this as a story you’re reporting, but it’s not about you.

Yeah. I thought it was going to be a biography of my father and I wouldn’t have a place in it.

So other than not wanting to write a memoir ever again–

[laughs] You know, I’m already working on one, right?

I’m in Australia on a Fulbright, and it’s been amazing. I’ve loved every minute. The proposal for this project was that it would be material for my third book, a very serious piece of conservation journalism. I sat down to write the first chapter the other day, and what do you think came out? All this stuff about my personal experiences here. I was like, no. Not another memoir!

You’re like, no! No more “I”! Not again! [laughs]

[laughs] I once read an interview with Lawrence Wright, who wrote The Looming Towers, and he said that all stories need a mule to carry them. I think in my books, after a period of writing and research and process of elimination, I’m just like, damn it, I have to be the mule for this story.

Every book needs a character. And sometimes the thing that connects all the pieces is just us, the writer. It’s as simple and annoying as that, right?

Exactly. We’re the lens through which the story is filtered.

_________________________________