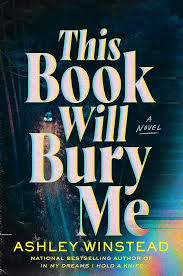

In her latest novel, national bestselling author Ashley Winstead dives into the very online world of amateur sleuths. This Book Will Bury Me depicts a motley group’s investigation of gruesome slayings at a university, loosely inspired by the real “Moscow Murders” of 2022 at the University of Idaho.

Written in the first person as a tell-all by Jane, a college drop-out reeling from her father’s sudden death, This Book Will Bury Me explores the consumerization of true crime and offers a poignant meditation on grief. It’s also a thrilling mystery with twists and turns aplenty, featuring an engaging cast of singular characters who clash and collaborate in order to solve the murders.

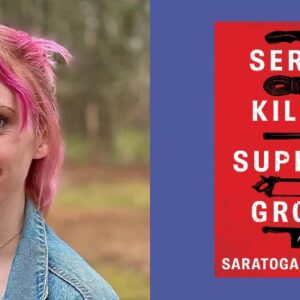

Winstead holds a PhD in contemporary American literature and lives in Houston, Texas. She is the author of five previous novels including In My Dreams I Hold a Knife and Midnight Is the Darkest Hour. I connected with Winstead over Zoom to discuss our cultural obsession with true crime, the power of chosen family, and the ways in which amateur sleuths help to dismantle the patriarchy.

Jenny Bartoy: How did this novel come to you?

Jenny Bartoy: How did this novel come to you?

Ashley Winstead: I have this definitive moment in time where I can look back and say, that’s where it started. I was out to dinner with a group of librarians after a big book festival and one was talking about starting a mystery and true crime book club for her library patrons, and the demand was through the roof. And I remember sitting at that dinner across from her, and it was a very interesting time in my life. My father had passed away only months before. He’d passed away young, and I had a lot of questions about why. I had also recently started paying attention to the University of Idaho slayings, this big case that had taken over the world of true crime throughout social media. And I remember feeling this absolute conviction, sitting there at that table at the Bonefish Grill, about why people were drawn to true crime cases, and that it was fundamental to human nature, like this inability of human beings to function in a world that doesn’t feel legible, when there’s a mystery and you don’t understand why. I felt like I could write about a young woman who is drawn to true crime the same way that I was, both because she’s grieving and left with a lot of questions about her own father that she can’t answer, and she finds amateur sleuthing to be an outlet for scratching that itch. That was the seed of it for me.

JB: Grief is palpable in the story, both Jane’s grief which leads her to seek answers and solve crimes, but also this sense of grief as motivation for the other sleuths — grief for the murdered girls, grief for their respective losses. Each of them is dealing with a facet of it.

AW: Grief was the underlying motive for most of the action in this book. I tend to do that in my thrillers. If I have come to an understanding about what motivates my main character and what they’re going through, I like to explore all the different facets of that same thing through the other characters and even have it mirrored in the person whose actions we would condemn. I love reading books where I feel a lot of empathy for people who are making bad decisions, when I feel like I can so utterly understand the villains or the antagonists. I like to explore all the different things that an emotion like grief can compel people to do, or in my other books, self hatred or toxic perfectionism, as a spectrum, and see different people’s reactions to it.

JB: That level of thematic consistency and the mirror effect you describe help to give the novel a great sense of cohesion. Chosen family is a big part of this story. It’s a topic close to my heart: I’m the editor of an anthology about family estrangement, and chosen family is often a life-saving force for the estranged. How does chosen family help Jane with her grief?

AW: For me, grief created estrangement. Obviously there’s physical, literal estrangement: you no longer have this father who you can talk to, communicate with, or hug. That’s gone. So I was really interested in exploring that distance and the uncertainty that person’s death introduces. With Jane’s found family, these internet sleuths that she becomes so close with but has never met, it was almost like an inverse relationship of the one with her father. She had her father physically there, and then he went away to a place she could no longer touch. Versus these people who start out physically where she can’t touch them, but then an intimacy is created nonetheless that breaches that distance. I found something very hopeful in that.

That kind of found family has always been something that I, as a consumer, as a reader, as a watcher, always gravitate to. And so I wanted Jane, who is feeling, post her father’s death, like her own family is dissolving, and she does feel estrangement from her mom even if it’s temporary, to find that family elsewhere. And God, it was so fun coming up with the personalities of these characters. I was determined that they were all going to have weird usernames so that I could call them ridiculous things throughout, like Mistress and Lord Goku. I think it’s important when you’re writing books that are dark and heavy in subject matter, to shoot them through with joy and have that balance.

JB: Father figures are important in this book too. Jane had a great father, Peter had an abusive father, and Lightly serves as a father figure for them both. You already touched on your own grief for your father, but I’m curious about the role of fathers in this story, thematically speaking.

AW: Even though this book gets the most personal for me in exploring father-daughter relationships, or just the beauty of such a relationship, I think from my very first book, I’ve had issues with fathers. Before I learned not to read Goodreads, a review summed up my first book in a really excellent way: “Daddy issues, but make it murder mystery!” That’s true of all my books. [In this book, I’m] also trying to explore the breakdown of paternalistic institutions, the messiness of it. Not to get too nerdy or academic, but I [considered] the idea of fathers being “institutional fathers,” this traditional, old-fashioned idea that institutions like the government and policing are sort of paternalistic sources of order and information, and that historically we’ve trusted in the authority of these institutional fathers. That this is deteriorating in the rise of true crime and amateur sleuthing is in some way an indictment of our certainty that these institutions can get things right, and are going to move fast enough, and are going to even just have answers.

JB: I definitely sensed a deliberate critique of patriarchy throughout — which was, for me, quite enjoyable! How much research did you do for this book, and what kind of rabbit holes did you explore?

AW: I have never researched more or fallen into more rabbit holes than for this book, which is probably fitting, because it’s about doing research and falling into rabbit holes, and about armchair detectives who make that their reason for being. I researched everything I could get my hands on that examined the phenomenon of true crime. In the book, I am including a bibliography of some of the resources that I kept returning to. For example, Savage Appetites by Rachel Monroe, which was so influential to me that it shows up in the novel itself, is a book about why women in particular are drawn to true crime. Don’t Fuck with Cats was one of the first documentaries that I watched that absolutely blew my mind in terms of what armchair detectives are capable of.

I wanted to make an argument in this book about why more and more people are drawn to true crime. Why is it that internet sleuths are sometimes so much better at the job than our more traditional law enforcement or investigation officials? That’s where I came to this hive mind idea. Armchair detectives have, en masse, an ungodly amount of hours and resources. I come out of academia, so I know firsthand the diligence of hours and hours of research, and that is the gift that they have to give cases. And then, of course, since this book is so deeply inspired by the case that hooked me, the University of Idaho slayings, I read every single piece of media both about the case and about the kind of bizarre and unprecedented reaction to that case.

Websleuths.com is the OG of internet forums, and that was the basis for RealSleuths.com that’s in the book. It’s a very analog-looking, very simple forum, no bells and whistles really. It’s just a bunch of human beings typing at each other, and I spent hours unspooling these insanely long threads to see how people were talking to each other. I loved getting to adopt that polyphonic voice in the book, where you get to be a frat bro talking to a grandmother figure, and the splintering that you get to play with when you’re trying to represent all the different voices in an internet conversation. One thing I found absolutely fascinating in my research is that the majority of sleuths tend to skew female and a little bit older — women who have a little bit more time on their hands to really dig into the sometimes mind-numbing research.

JB: You write about how much attention is paid to young murdered girls. What are your thoughts on this cultural obsession, and its particular demographics?

AW: I came across this quote from Edgar Allen Poe, “The death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.” I think that the role that beautiful dead girls have played in our collective imagination, in our cultural imagination, is so outsized and it’s much more long-standing than the true crime boom. Why do certain cases get so much more attention? What is it about these cases that sends a lightning bolt through our collective imagination? Maybe the answers aren’t so new, but just a really old phenomenon, and true crime is just another way that it’s manifesting. The idea that there is something indescribably romantic and tragic about a beautiful, dead girl plucked in the prime of her life with so much potential — a lot of smart people have written about this and it’s got a name: “missing white girl syndrome.” Part of me was questioning the University of Idaho slayings in which four young people were tragically killed, three of them beautiful young women, all white.

A young, beautiful woman being dead on the one hand is such a tragedy, because this is the platonic ideal of what a woman should be, according to this traditionalist model. But on the other hand, could a woman get more perfectly submissive, when you’re, in short, freezing her in time? You’re idolizing her. She’s silent. What a virtue. She can’t rebel. So she is like this perfect person to project upon, right? What you see with the University of Idaho case, and what I tried to do in my book too, was show the realities of these young women. These are kick-ass brilliant young women who are much more nuanced and complicated than these projections and who they become to the sleuthing hive minds. I’m interested in reinstating the complexity and the flaws and the darkness. These beautiful dead girls have been stripped of all of that so they can be these perfect paragons.

JB: I’m curious about how we choose to tell stories: what is shown, what remains hidden, and why. This book is written as a tell-all from the voice of a 24-year-old amateur sleuth and college dropout who’s struggling emotionally. Tell me about choosing and inhabiting this narrative voice on the page.

AW: Jane is one of my younger protagonists, and that choice was deliberate, because I wanted her to make choices and have questions that someone my age maybe wouldn’t. And so Jane is doing eyebrow-raising things like hugging her father’s ashes to her chest, and these things that are a little more childlike, but I felt like there was maybe a little more leeway with making Jane that grieving child that was inside of me.

This book didn’t really crack open for me, until I figured out that I wasn’t going to be telling this straight, narratively, but it was actually going to be this tell-all, this release of all of Jane’s dirty secrets and all of the things that she has tried so hard to keep out of the news. Because of her experience dealing with the police as an amateur sleuth, she is very aware of how mediated information is, and how selective what the folks at home see and hear is, and how both the police and journalists are constantly making choices about the narrative they’re telling. And hopefully the reader understands as they’re reading that Jane herself is being selective and purposeful in the way that she’s presenting information. That was so fun for me, because I love to play with unreliable narrators. There is no such thing as a reliable narrator, in my opinion. But I love making that really obvious to a reader.

I think when you’re writing mysteries and thrillers, you’re always looking for how to make your main character an outsider, because it’s so valuable to have that fish out of water perspective. And so Jane is constantly the baby of the group. She’s the one that people are explaining things to and patting on the head. And so I think that was really useful for me to have her occupy that space. She is both the victim demographic and the consumer demographic.

JB: What does the future of murder investigations look like, in your opinion? Are the true crime industry and the reign of amateur sleuths here to stay?

AW: Yeah, I think it’s absolutely here to stay. Police are finding more and more value, and understanding true crime communities more and more as a resource that they can tap into. I predict that law enforcement will make greater use of these informal networks of research and folks. I think there will be more coordination, as we saw with the Golden State killer and that case being solved, where the police turned to this woman, Barbara Ray Venter, and slipped her DNA because they couldn’t access the 23andme network. I just see it escalating in the future. We’re going to see more true crime sleuths out of TikTok and boots on the ground in places where crimes have happened.