Detective fiction? Let’s start with Bertrand Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, logician, historian, philanderer-philosopher (epistemology can send a girl limp) and improbable Nobel laureate for his thoughts on marriage. In the year we’re interested in—he was in his late sixties by then—the British Earl expected to travel his long distances by train. Riding in first class, naturally, and prefaced always by a visit to the station bookstore before boarding. There, as the story goes, he would buy himself a hatful of detective yarns, each one to be leafed through in turn on the journey and all of them left behind in the train when he got out. They were his chin-ups for the brain. The lightning logic problems he solved for relaxation. Me, I like to think of him at the Los Angeles Union station that year, climbing up into the Super Chief ahead of a Hollywood star or three, trailing the car attendant to his sleeper with the books clamped under his arm. Better yet, I like to suppose that one of those detective yarns might have been The Big Sleep. Why so? Because, settling into an evening’s glow in the club car with Raymond Chandler’s new, first, book-length mystery, the old boy wouldn’t have had the first clue what was coming. It’s fun to imagine him biting through the stem of his hooked briar, steam whistling from his logician’s ears, as he found out what. You see, The Big Sleep, and Chandler’s canon of full-length, private-dick melodramas generally, don’t test high on logic.

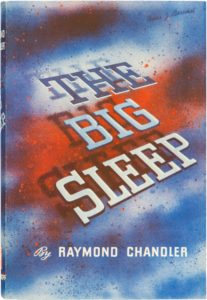

All of that scene on the Super Chief is at least possible. The Union station had opened in May 1939. Russell had been a visiting professor at UCLA since March. Before that he’d been at Chicago, a ride of 40 and more hours and the train’s destination. Then as now, he could change there for New York, where he went to teach after UCLA. As for The Big Sleep, it was published by Knopf in October, just weeks after Russell’s home country had gone to war with Nazi Germany. The book is eighty years old.

It’s even possible—assuming the 3rd Earl had been picking up his Black Mask or Dime Detective at the newsstands—that the name Chandler might have struck a chord. But it still wouldn’t have prepared him any. By 1939 Chandler had worked a seven-year apprenticeship writing for the mystery pulps, absorbing the craft and getting the passages that most interested him—let’s call them the atmospherics of the story—routinely cut out. In The Big Sleep, with a novel’s word count at his disposal for the first time, they stayed in. And their author changed the face of mystery writing.

* * *

If an octogenarian Big Sleep is a shocking thought, consider that Chandler was already fifty-one when his vanguard mystery saw light of day. Chicago-born but taken young to Victorian London, he’d packed an English public school education along with an interest in poetics, and re-crossed the Atlantic before the First World War. He was in his mid-twenties then, in need of a future, and—taking the long view—the move back worked out for him. Chandler learned book-keeping, went to war himself, made and then unmade himself as a California oil executive (the unmaking just one consequence of testing seriously high on alcohol for most of a lifetime). Finally, down and out of a job in Depression-era LA, he turned to pulp writing. Not as a slumming poet, but as a man eyeing a craft he thought he could learn. Only get the hang of it and the pulp magazines were paying out a penny a word.

Get the hang of it he did, but the pulp detective form grated on Chandler. It’s hardly a surprise. His Belle Epoque English schooling had taught him that a writer’s sense of style was everything and Flaubert was all the rage. Not bad for a model, but this was Dime Detective, 1932. Chandler’s interest in writing the atmospherics of a story was being nixed not only—or even mainly—because words cost pennies. But because they were costing the publishers their action.

Chandler didn’t see that as any great loss. What’s more he didn’t think pulp readers would either, if ever they got a chance to try his alternative. Likewise—pace Bertrand Russell, most of the critics and the (generally English) crop of detective fiction writers of the time—he thought their refined plot lines were fripperies. Which didn’t sit too well with The Murder in the Samovar coterie. They had their rules and unities for sleuthing by the book, and they kept them patrolled. Eighty years ago, when Chandler turned out a full-length story that shattered all their commandments, naturally they gave it the freeze.

* * *

From the outset then, Chandler’s novels aren’t paying too much attention to writing action or the working out of a plot. And if you want to take his word for it, he doesn’t expect to burden a story with any significance either, social or otherwise. After all, why would you set out to write gumshoe fiction if you wanted to change the world? In Chandler you’re meant to take the atmospherics on their own terms. Join him under the floodlight of a parking lot. Breath the scent of a diner drifting in a window. Follow the aimless tramp of the Pacific or tour around the bleak living of the fast and the monied, corrupting in a California glare. But don’t ask what it all means. There are a thousand such atmospherics in The Big Sleep and in the novels that followed it. Some of them are indelible. Some rise to the magical. But Chandler means them to stand for nothing outside themselves. What he does lay claim to is a burlesque of the hardboiled genre, shifted up through the gears by an art and originality that belongs in the writing alone. For him, it’s the only way a writer makes the grade.

Of course that may just be Chandler the Belle Epoque stylist, always resistant to attaching any significance to art. But there’s no doubt either that the art is holding up a mirror to the Los Angeles of its time; fast industrializing and overgrowing even as Chandler hit his writing stride. From The Big Sleep onwards his burlesques parade a re-minted California before the mystery reader: California become dark and brittle, decadent but nervous, permanently grifting, nickel-plated, always skin-deep.

In fact, a California tailor-made for Chandler’s own priorities as a writer. Its citizens’ behaviors appear fragmented and incidental, any idea of meaning there would seem quaint. Its atmospheres are its sum, and they run no deeper than the paint on the switching scenery. The irony being, of course, that since The Big Sleep first opened mystery readers’ ears and eyes and noses to them, those very atmospheres have become a signifier for LA the world over, just as much for generations who never heard of Chandler as for his enduring fans. The atmospheres, it turns out, have become the meaning. Dammit, Raymond, was there more to you than style after all?